From Brooklyn To Bangladesh, Borough Hall Remembers Traffic Crash Victims

BOROUGH HALL – “Traffic crashes do not discriminate by religion, race, age, sex, political affiliation, or neighborhood,” Devan Sipher, a member of Families for Safe Streets said.

The first thing one noticed when entering the Borough Hall yesterday, Nov. 18, was the empty chairs. On them, were yellow paper with names of people that died in traffic crashes this year. Some of them had yellow flowers sitting on the seat that perhaps, they would have sat on if they were alive on the World Day of Remembrance. Later on in the event, the names of all of the victims that died in 2018 were read aloud in a powerful few minutes.

The majority of people in that room had lost a loved one to a traffic crash. Take Sanjeeta Batlani, for example. Her son was killed in a crash in June of 2011. Or Amy Cohen, the mother of Sammy Cohen Eckstein, a 12-year-old kid that was killed in 2014 in Park Slope.

There were also survivors of crashes. Ronica Kelly was hit by a turning car. The driver had one hand on the wheel and the other on her phone. “They say the reason I survived was that she instinctively slowed down when she was turning,” Kelly said. Kelly suffered a traumatic brain injury.

Some were there to show their support. Kashif Hussain, who ran for District Leader, was in attendance with his 14-year-old son.

“I lost family and friends to traffic accidents from as early as 2001 to as recent as 2018,” he said. When 14-year-old Mohammad ‘Naiem’ Uddin was killed in a hit and run in Kensington in 2014, Hussain heard it on his radio as he was patrolling.

“I went to the hospital and saw firsthand the feeling of a mother losing a child. You ask yourself, that could’ve been my son,” he said. “I bring my son to these events, the good and the bad, because maybe when he’s 18, he’ll have something from me to hold on to.”

Sipher was run over by a double-decker sightseeing bus on July 3rd, 2015. He was crossing the street on a crosswalk when the driver raced through the stop sign. He was dragged and pinned underneath the bus.

“I shouldn’t be here today. I shouldn’t be alive,” Sipher said. “There’s a video on YouTube of a river of my blood flowing down Sixth Avenue.”

He was taken to Bellevue Hospital and stayed there for three months. It took two months before he could stand. “It took two months before my wounds could heal; the physical ones.”

Though the incident happened three years ago, he still goes to physical therapy every week and has “neuropathic pain that feels like someone is trying to cut off my toes with piano wire.”

He asked everyone to stand or raise their hand if they lost their spouse to a traffic crash, or their friend, or their sibling. The hardest one was a parent who lost their child.

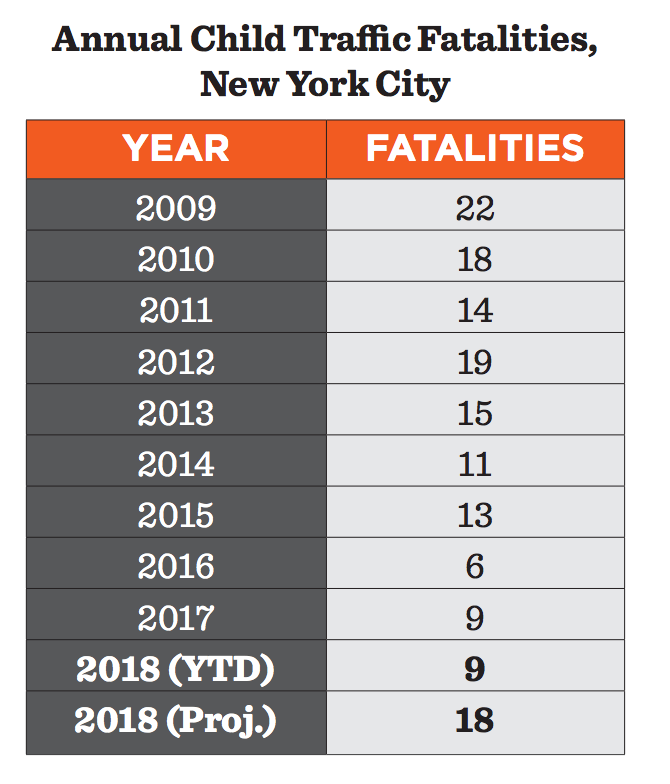

“Sadly, the epidemic of traffic crashes is one that unites us all,” he said. Analysis by Transportation Alternatives in June of this year found that “in less than six months, drivers have already killed the same number of children killed in traffic in all of last year.”

“This is an epidemic. But unlike many epidemics this is one is preventable,” Sipher said.

For this year’s World Remembrance Day, Bangladesh was represented in Brooklyn. On July 29, a speeding bus ran over a group of students in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Ten young people were injured and 18-year-old Abdul Karim Rajib and 17-year-old Diya Khanam Mim were killed. The incident sparked protests all over the city, including right here in Kensington. Following the death of two students, NPR reported that thousands of high schoolers and college students (including children as young as 13) spread out across Dhaka and “station[ed] themselves to direct traffic and make sure vehicles stayed in their lanes.”

One of those students was 10th grader Sanjida Afrose from the Urban Assembly School for Criminal Justice located on the edge of Borough Park and Kensington.

“Why is the death rate in Bangladesh so high? It’s because Bangladesh’s road system doesn’t have any organization,” she said. “People cross and cars go at the same time.”

“Children should not have to fear going to school and making it there alive,” she said. “Parents and adults should not have to worry about making it home to their families safe. It shouldn’t be a norm where people die in certain deaths that could have been prevented from the beginning.”

Borough President Eric Adams recalled his early years in the police department watching the transformation of South Africa during the Apartheid.

“It became a global conversation,” he said. “People were being prosecuted in their homelands. Until the conversation cascaded outside the walls of Johannesburg and Cape Town… did it become real.”

He remembered the times he would knock on the door and tell someone that their loved one was killed in a crash. And he commended Families for Safe Streets and TransAlt for the work they have been doing, which includes standing outside Senator Marty Golden’s office in the rain to demand he call on the Senate to reconvene and pass the speed camera deal — which he did.

“What you have done is you have turned your pain into purpose. What you are accomplishing is saving lives globally,” he said. “You need to acknowledge your great achievement. It didn’t stop here in Bensonhurst, Brownsville, or Bedford Stuyvesant. It reached the voices of people in Bangladesh.”

Mary Beth Kelly is a sweet woman who always seems to be smiling. The love of her life was killed in a traffic crash 12 years ago.

“There’s a song from the musical Hamilton. ‘Who lives, who dies, who tells your story.’ That is what we do. We are the living and we tell the stories,” she said. “In 1976, my husband took an oath that all physicians take. ‘Do no harm.'”

“But 30 years later, as we were riding our bikes together, terrible harm was done to him by a tow truck who failed to yield at an intersection.”

“If we had the antiviral serum for an infectious disease, we wouldn’t go to our community boards and say ‘Please, can you bring this to our communities?’ ‘OK. We’ll give Chelsea the antivirus, we’ll give Bay Ridge the antivirus, but we won’t make it available to this whole city.'”

“This is a worldwide crisis and it is one that we can end,” she said. She called for street redesigning, education, and enforcement. Vision Zero is doing great work, she said, and we need to support it.

“Families for Safe Streets has made traffic violence an issue that can no longer be ignored in New York City and beyond. We’re seeing tremendous progress toward Vision Zero, but the City can and must do more to make safer street redesigns more routine,” said Joe Cutrufo, a spokesperson for TransAlt. He said one way to do that is by codifying the Vision Zero Street Design Standard, which a majority of City Council members have endorsed.

“Roads have stories. Ours is a group which no one should have to join,” Sipher said. “Together, our combined trauma and pain have created waves and those waves are becoming a tsunami that will not, and can not be ignored.”