Deborah Lauter on Hate Crimes, Segregation and Standing Up Against Threats

CITY HALL – Hate crimes have spiked all over the country. They have risen in New York, but more particularly in Brooklyn. A few weeks ago, a young Muslim woman was spat on and harassed on the bus. A few days later, a Jewish man was assaulted in Crown Heights when someone threw a massive brick to his face. This week another orthodox man was attacked, and swastikas were found at Ditmas IS playground.

As of May 2018, there were 58 reported hate crimes directed at Jewish people that year, while 2019 as of the end of May has seen roughly double that amount—110 anti-Semitic hate crimes—according to NYPD statistics. Overall, hate crimes were up 64 percent, the NYPD says, and 60 percent of the total hate crimes were against Jewish people—particularly in areas home to many Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn.

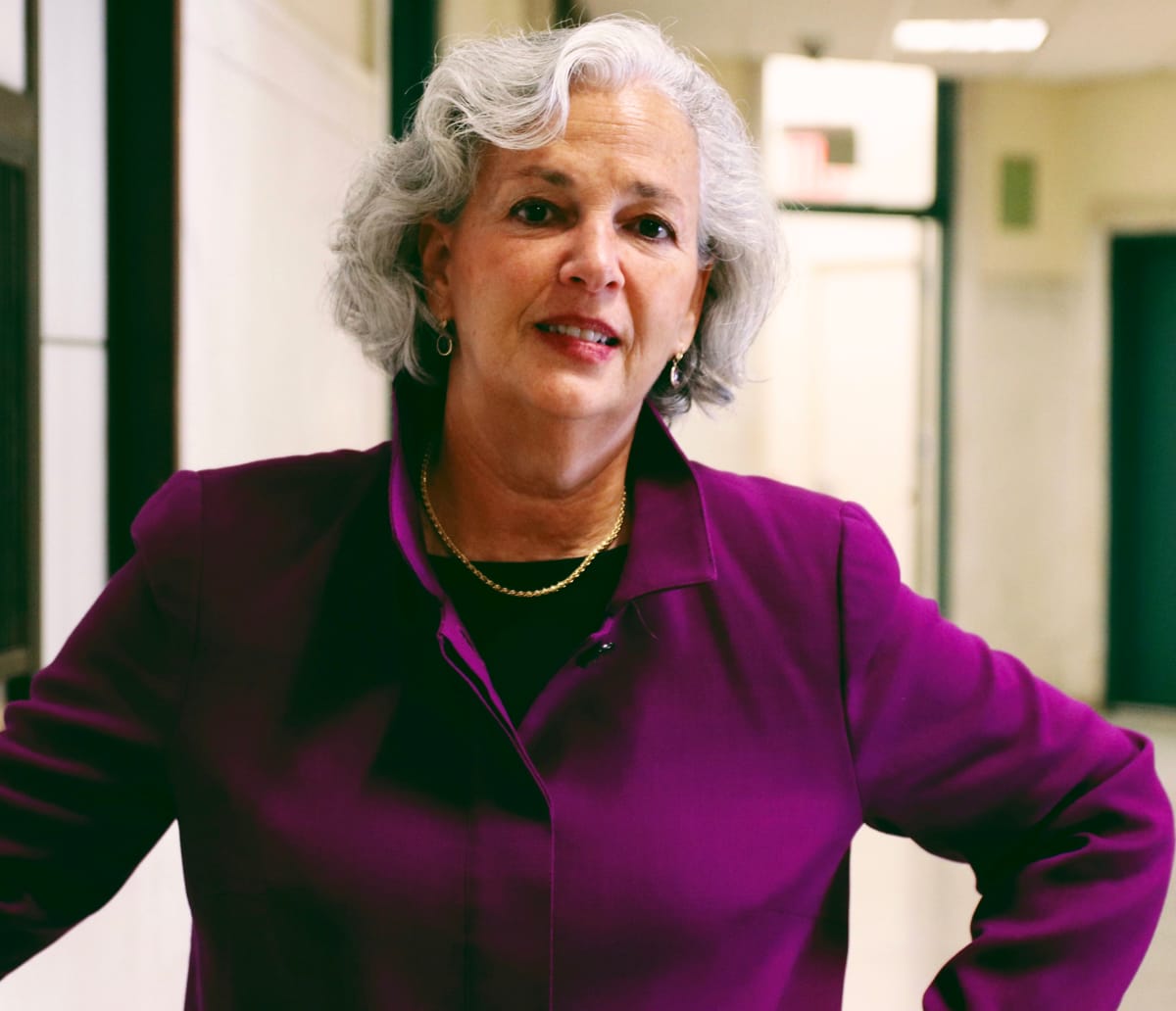

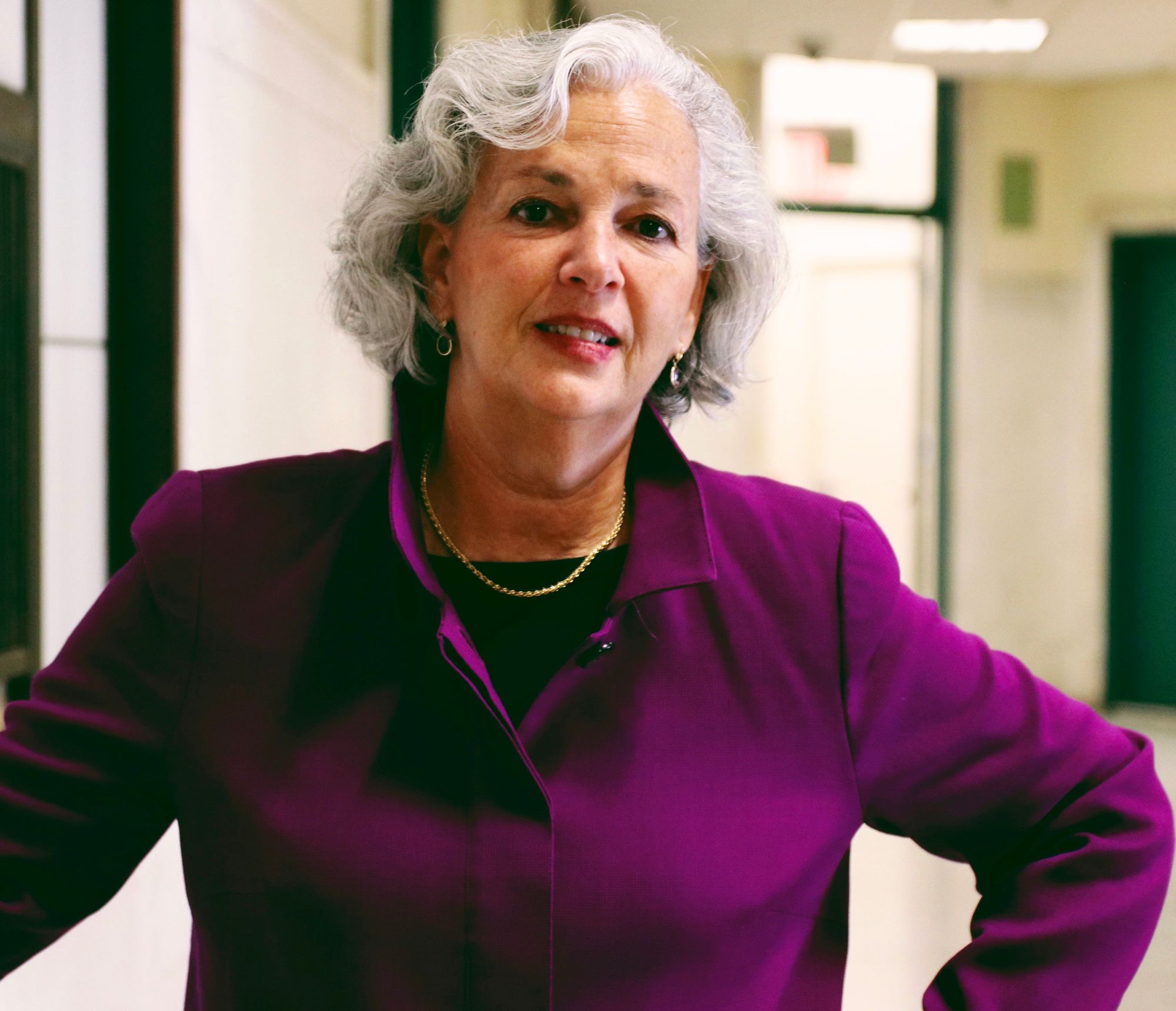

To try and figure out the underlying causes of these hate crimes and how to best reduce them, Mayor Bill de Blasio launched the NYC Office for the Prevention of Hate Crimes (OPHC). We spoke to its executive director Deborah Lauter about what it means to be tasked with such a responsibility.

Lauter’s office is across the street from City Hall at One Centre Street. It’s on the tenth floor, but it takes a minute to find as the new office doesn’t have signage yet – Lauter has been in this new role for a little over two weeks.

OPHC will serve as a coordinating body for the various agencies already working on aspects of hate crimes, she told us.

“The vision for this office is to look at the whole issue holistically. At the same time… we’re going to coordinate an interagency committee where they each share what they do, the best practices, looking at where the holes are, and making sure everyone really understands some of the technicalities of hare crimes,” Lauter said.

What Is A Hate Crime

One of the many things Lauter wants to work on is figuring out how more victims of hate crimes can come forward.

Some of that is related to people not knowing what is and isn’t a hate crime: Hate Crime is defined by the intention of the perpetrator of the crime.

In the Muslim and immigrant communities, she noted, hate crimes are often underreported, and it may be because they do not have a trust relationship with law enforcement. The key to that is working with community-based organizations, she said.

“The Jewish community has established more of a trust relationship over the years after our main immigrant wave. It might be interesting to have them share how they got to that point,” Lauter said. “It could be an interesting model. It’s one of the creative things I want to work on that would also break down silos between communities.”

Hate Speech Is Protected Speech

Another form of harassment Lauter and her office want to try and navigate is one that takes place online. She noted it’s difficult because communications are not considered a hate crime, rather, hate speech, “which is protected speech in this country.”

“To what extent of the atmospheric of online hate inspires people to incite?” she asked. “If you look at the major attacks, particularly in the Jewish community in the last year, like at the Tree of Life synagogue, we can document now that it was inspired by an extremist ideology that was going online. How can that be interrupted? There has got to be a key element.”

Segregation

Though Brooklyn is diverse, it is also segregated, whether it’s among the school system or among the different communities. Lauter agreed, and said there could be a solution to that, too.

Last weekend she sat in as an observer at a community conversation on hate that took place as part of #OneCrownHeights Festival. One of the participants said she often sees segregation in the parks. So, after the meeting was over, Lauter went to a park and sat down to watch. It was at that time, she experienced one of those great New York moments everyone speaks about.

“I witnessed this youth soccer league. The coaches and referees… were Orthodox. There were girls in hijabs. There were white boys… these kids were just playing soccer,” she said. “There are things like that going on. One of the roles of this office may be to look at those best practices. How do you normalize that?”

Education

In Brooklyn, there have been hate crimes taking place in Crown Heights against the Jewish community, in Southern Brooklyn against the Muslim community, and in Bensonhurst against the Asian community. Earlier this week, swastikas were found drawn on a chessboard at Ditmas I.S 68. Cops say it is under investigation.

“Some of the kids who are acting out with swastikas probably have no idea what it means, and maybe some of it comes from parents,” Lauter said. “My mom would always say ‘Children learn what they live.’ So if a parent is engaging in racist comments, the kid’s are hearing it.”

“So, what can we as a society to interrupt or stop that?”

Lauter noted that the new office is not going to be able to solve all of the problems. She said she recognizes that it will be a challenge, but her philosophy has always been, “When good people stand up to hate, we can make things better.” So they will focus on working with schools and educating kids.

Standing Up To Hate

“If we do a really good job, particularly with the vulnerable communities, and they start reporting, the numbers are going to go up, and everyone is going to say, ‘Oh, well you had this office,'” Lauter said of measuring success.

“The metrics are going to have to be long term. There’s not a quick fix to this.”

But Lauter is prepared. Before taking on her new roll in City Hall, Lauter worked at the Anti-Defamation League for 18 years fighting anti-Semitism and hate. Her whole life has been devoted to fighting against such crimes.

“I care deeply about democracy. My parents were first-generation Americans… I learned early on, more from a church-state perspective, the importance of Consitution and democracy,” she said. “If you look at the Jewish identity, we know what it’s like to come from a place that didn’t have strong democratic foundations, or how easily the foundations crumble.”

“I look at the Holocaust and think that if good people had stood up, it wouldn’t have been. I’m not saying that’s going to happen here… but you can learn things. I just think very deeply about what it takes to make America strong,” she said. “You have to look at the threats and you have to stand up to them.”