Fighting Sex Trafficking in Brooklyn

BROOKLYN – “Sex trafficking in Brooklyn?” – This very question made a young woman create a documentary, a young survivor tell her story, and a historic Brooklyn Heights church take a big step to help combat sexual exploitation in the borough we call home.

“We Are the New Abolitionists” is a new ministry at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights, chaired by Beth Fleisher and aimed at stopping sex trafficking.

Sex trafficking: Occurs when someone uses force, fraud or coercion to cause a commercial sex act with an adult or causes a minor to commit a commercial sex act.

Plymouth Church was founded in 1847 by Henry Ward Beecher and has a rich history in social activism – Abraham Lincoln prayed in pew 89, it was a stop on the Underground Railway, and on February 10th, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “The American Dream” speech. It was only natural for them to take up the cause, first brought up by Brooklyn College philosophy professor Dena Shottenkirk, a congregant, about five years ago.

“A major part of our faith is to act out our faith in the world,” Fleisher told BKLYNER. “We’re not doing anybody any good if we just sit inside our little house and talk to ourselves. We believe that whatever is done to the least of us, is done to all of us. And we have an obligation to help others.”

“Although labor trafficking is something that also happens in Brooklyn and concerns us, we decided to only focus on one aspect of trafficking for it to be effective,” Fleisher said. “We certainly are against any form of slavery anywhere in Brooklyn, the City, or the world.”

This past Sunday, January, 28th marked the start of their year-long anti-trafficking campaign. It began with a public forum at the church, “In Our Backyard: How to effect change for trafficking survivors in our community.” Throughout this year, the church will work on fundraising for various organizations working to fight sex trafficking across the city.

Over the last five years, Fleisher and the congregation collaborated with several organizations that work with survivors of sex trafficking, such as Restore, Sanctuary For Families, and Ending Child Slavery At The Source (ECPAT USA).

They created care kits, in collaboration with Sanctuary for Families, that can be given to those victims of sex trafficking that get picked up and taken to the Human Trafficking Intervention Court in Queens. Usually, they will need a change of clothing. Members of Plymouth Church created care kits that include clothing, toiletries, and a signed handwritten note. It’s all about that human connection, Fleisher explained.

“One of the things that trafficking victims need is to know that they have worth as a person,” she said. “One of the control methods of their traffickers is to tell them they have no worth and that nobody cares. So everything we do is not just buying stuff and giving it to people, it’s to make sure there’s some sort of connection.”

In the Queens court, the victims are given two options: they can either be convicted of a felony or attend a number of counseling sessions all while having their charges dismissed and records sealed. “It’s a trigger mechanism to establish contact between individuals and service providers,” Judge Serita told the New York Times. “We know that five sessions is not necessarily going to change some people’s lives, but if they can establish meaningful contact with somebody else that can be used in the future, that’s what we’re hoping for.”

“Ashley” is a 25-year-old woman who spends her days reading. She has a three-year-old daughter. You wouldn’t suspect from looking at her smile or her curiosity while she gazed at the historical paintings at the church, that she deals with depression. Or that most of her uncles are pimps. Or that six years ago, she was sexually exploited.

When “Ashley” was 18, her cousin got her involved in the sex trafficking business. Over the course of the year, she was raped and physically assaulted by many pimps. When she was 19, she risked her life and escaped her trafficker.

“It comes with threats and beatings. The pimps I dealt with, if I were to speak with my mom, I’d get beat for it,” she told BKLYNER. “And if you’re not cooperating, they might keep you in the house and have guys do whatever they want.”

“To them, we’re just their ATM’s,” she said.

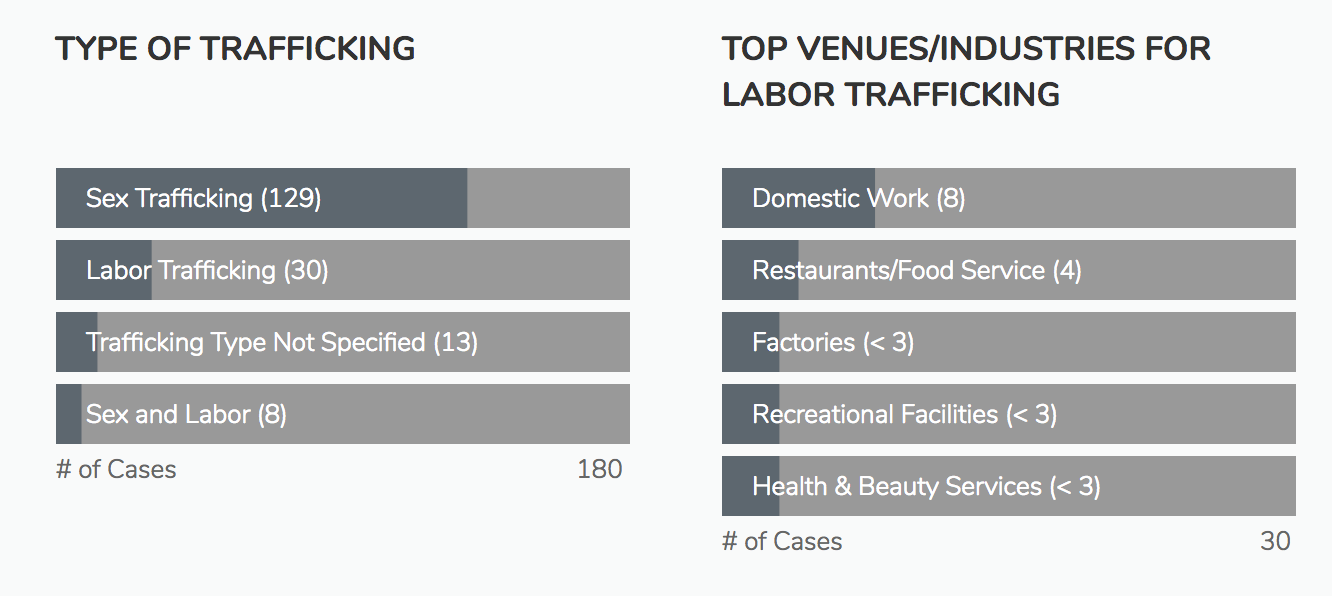

Some facts from a 2017 US Senate report, NYS Anti-Trafficking Coalition, Restore NYC, and Girls Educational and Mentoring Services (GEMS):

- Over eight in ten suspected incidents of human trafficking involve sex trafficking.

- Human trafficking is an organized crime, a $32 billion a year global industry.

- There are an estimated 57,000 people living in exploitation in the US, and NYC is one of the largest destinations for trafficked women entering the country.

- NY is the fourth worst state (behind California, Texas, and Florida), with over 2,000 children trafficked each year.

- Though women, children, men, and the transgender youth are among those who are sexually exploited, 85 percent of victims are females.

In 2017, 47 individuals were charged with promoting prostitution in Brooklyn, up from 39 individuals in 2016, the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office told BKLYNER.

Those who are sexually exploited are embarrassed, ashamed, and afraid, Fleisher said. And often times, they are fearful to report to any sort of authority because they believe they might be prosecuted, which is why trafficking statistics don’t take every single survivor into account.

It’s also difficult to pinpoint exactly how many hotels, houses, or massage parlors are being used to exploit victims. “Sex trafficking is an illegal activity,” Fleisher said. “Not many people are self-reporting that they are a trafficker or that they are a John.” But what can be pinpointed are the online websites that enable prostitution.

About 70 percent of child sex trafficking survivors that were surveyed in a study by Thorn, were at some point sold online. Craigslist “is notorious for advertising sex work,” Fleisher said. In 2009, South Carolina’s district attorney filed a lawsuit against Craigslist. He had set a deadline and made an offer: the company could permanently remove portions that were related to prostitution, or it could face criminal prosecution. In response, Craigslist filed a lawsuit to block the attorney general from criminally charging the site and the judge ordered the attorney general to stop pursuing criminal charges.

Backpage is another website, similar to Craigslist, that “has become a de facto hub for online prostitution,” the Boston Globe reported, with about 80 percent of its content being sex advertisement. Backpage has gone to court at least four times.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act states that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” The court decided that though Backpage did make sex trafficking easier, it did not create the content itself. The court then cited Section 230 and the First Amendment.

“Showing that a website operates through a meretricious business model is not enough to strip away those protections,” the court said. “If the evils that the appellants have identified are deemed to outweigh the First Amendment values that drive the CDA, the remedy is through legislation, not through litigation.”

Though online websites are not the only ways for victims to get sold, prostitution will continue in massive numbers as long as they exist, including right here in Brooklyn.

In 2009, the NY Post reported about a 15-year-old girl who was smuggled to Brooklyn from Mexico. When she came to Brooklyn, she was turned into a prostitute.

In August of 2017, two men and a woman were indicted after one of their victims escaped the Crown Heights apartment where she and another girl were being held captive and forced into prostitution.

“This has been happening in Brooklyn probably long before it was called Brooklyn,” Fleisher said. “If you think about it, there is no society that doesn’t have a problem with sexual aggression and rape. So as long as there are people, there is going to be problems like that.”

Getting the community to realize that people are being sold for sex in their very city is the first step in tackling the problem.

Danielle Rose took an anthropology and film class while she was an undergraduate at Columbia University that sparked her interest in documentaries.

When she first heard that that sex trafficking was a huge issue in Brooklyn, she could not believe it. “Sex trafficking in Brooklyn? It’s the same response I get when I tell people what I do,” Rose told BKLYNER. “I wanted to eliminate that response.”

“In Our Backyard.” is a documentary she produced that tells the stories of victims/survivors, activists and politicians working to end sex trafficking.

“Focusing on Brooklyn, as a filmmaker, it brings you smaller, but at the same time it makes you realize if this much is happening in Brooklyn, how much is happening in NYC, and the country, and the world?” Rose said.

Shandra Woworuntu is one of the survivors Rose features in her film. Woworunto lived in Indonesia when she saw an online advertisement for a waitress job at a hotel in the US. She arrived at JFK Airport and met a man who delivered her to another man in a hotel in Queens. She saw money being exchanged. From then she was kept in attics, raped and abused, and “was sold for $120 to $350” to countless men every 45 minutes, she told PIX 11 in December of 2017.

Woworunto, fearing for life, decided to jump off the second-floor window ledge in the Sunset Park apartment she was being held in. She eventually got help and now is an advocate, just like “Ashley,” the other survivor.

“I learned how brave every survivor is that I’ve met,” Rose said. “What’s happening now is that survivors are taking this on, are at the forefront and have created a community between each other, and I don’t think that gets enough credit.”

Rose has presented her award-winning film at various screenings and festivals, including at Plymouth Church.

“So many people come up afterward and cry,” Rose said. “I’ve had people write to me to just say their thoughts on prostitution are different because they realize everything is not that black and white. There’s a rawness to the film that you can’t ignore.”

The film was the first time “Ashley” got to tell her story.

“I wanted to tell my story so bad, I just couldn’t find the right person. It’s like you don’t know what’s everybody’s motives are,” “Ashley” said.

But then she met Rose.

“It wasn’t just this person who was taking my story and would then go separate ways when it was done,” she said. “I don’t feel like I’m being used, or that I was just needed for this. We have a friendship we’ve grown and now nobody can break that bond.”

Rose, along with Rose’s family and boyfriend, have stuck with “Ashley” for a long time. They’ve supported her in school, help her every day, and Rose’s boyfriend even tutors her in math. They were there with “Ashley” in court, when she got every single one of her pimps in jail.

It is extremely difficult for survivors to press charges and get their traffickers in prison, as they have to make eye contact in court and share their traumatizing stories from the beginning. It requires a lot of courage and bravery, and “Ashley” did it.

“That wasn’t easy. I just wanted to let him know and give him that message that he might think that he destroyed me, but he didn’t,” she said. “I’m still going, I’m still living and I’m still going to talk about it.

She found out that another girl was raped by the same man she was. When “Ashley” began the process of pressing charges, the girl left the state because she was too afraid.

“I wanted to make a difference. I met a lot of girls whose moms had gotten them in the life, whose father had gotten them in, and when I realized nobody was speaking up, I had to do something different,” “Ashley” said. “I had to not only help myself but show these girls that they can speak up, too.”

“Somebody has to start something,” she continued. “A change has to be made, why not with me?”

“There’s a lot being done, but it takes a lot of time to turn a ship,” Fleisher said, “and the ship for a long time was sailing in the direction, ‘well these people have chosen this life of crime and sin, heck with them,’ and now very slowly we’re looking at the victims as victims.”

“We all think that if we were here in the US at the time of the Civil War, of course, we would all be anti-slavery, and we’d be working to fight slavery,” Fleisher said. “We can’t just look at the past and say ‘oh that’s over and done with.’ It isn’t.”

“For a civilian, it’s really simple. ‘Oh my goodness, I’m noticing that the person here seems to be working in this really iffy nail salon, and the curtains are drawn in there and I see that things don’t look right. Oh, I can call the NYPD hotline,'” Fleisher said. “Don’t hide behind yourself and think all of the civil rights stuff is done with.”

Restore, one of the organizations Plymouth works with notes that the majority of referrals that come in are from women sexually exploited in illicit massage parlors. “For every Starbucks in New York City, there are 4x more illicit massage businesses.” It is the same massage parlors we pass by every day.

Just a few months ago, 32 massage parlors in Bensonhurst were shut down. Back in 2014, we reported on nine massage parlors in Bay Ridge and Bensonhurst that were shut down in another prostitution sting. A total of 15 women were arrested: two were charged with promoting prostitution, nine were charged with misdemeanor prostitution, and 10 were charged with providing unlicensed massage services.

But there was a change in mindset last year. The NYPD announced that it was doubling the size of its investigative human trafficking squad. Instead of focusing on arresting prostitutes, the NYPD is turning its attention on pimps. NYC also has its own trafficking hotline, along with a national one, in an effort to help victims.

“If you think #MeToo is a campaign and that women have been sexually harassed in the workplace,” Fleisher said, “wake up and understand that young girls, women, transgender youth, and males are being sold for sexual services against their will, right now, probably within a half mile from here.”

Keep your eyes open, Fleisher advised, because it can save someone’s life.

“I’m praying that this film goes further,” “Ashley” said, “that it helps out more people other than in Brooklyn and all borough and all states, and a lot of girls speak up and come under the realization that they don’t have to do this anymore.”

How to help:

National Human Trafficking Hotline: 1-888-373-7888

Brooklyn DA’s Human Trafficking Unit: (718) 250-2770

NYPD Trafficking Hotline: (646) 610-7272