Rezonings Underestimated Development and Displacement in both Williamsburg and Park Slope, Study Shows

WILLIAMSBURG/GREENPOINT/PARK SLOPE — Rezoning gentrified the rezoned neighborhoods and displaced communities of color, a new study shows.

The study, conducted by Churches United for Fair Housing (CUFFH), looked at two rezonings – the Greenpoint/Williamsburg waterfront rezoning in 2005 and the Park Slope/4th Avenue rezoning in 2003.

CUFFH is an organization that works toward creating inclusive communities that are affordable to all, and is immensely involved in community organizing and tenant/immigrant rights.

The study suggests that these rezonings brought changes that the City did not anticipate, among them:

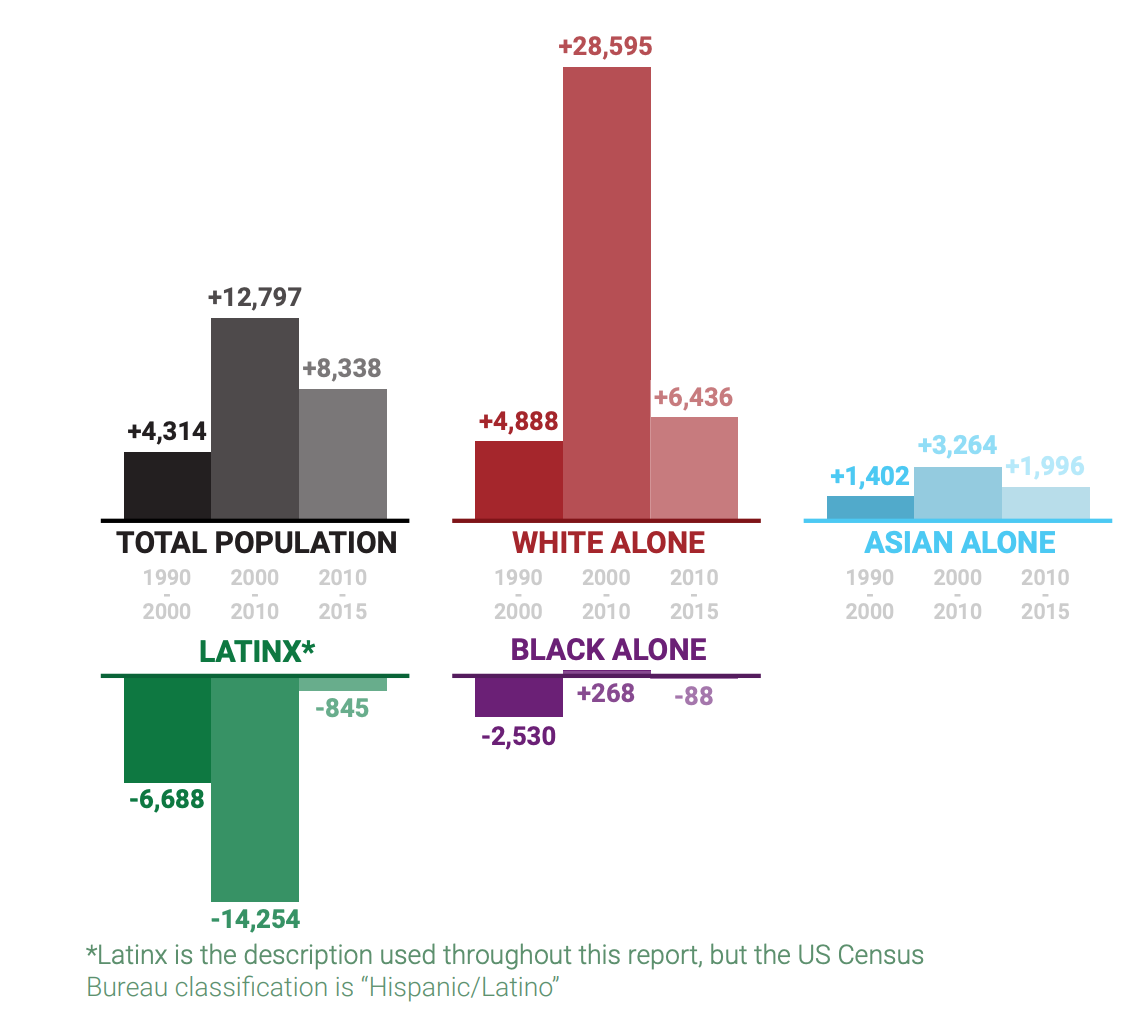

- Decrease of about 15,000 Latinx residents in Greenpoint & Williamsburg between 2000 and 2015 despite a population increase of over 20,000 during the same time period.

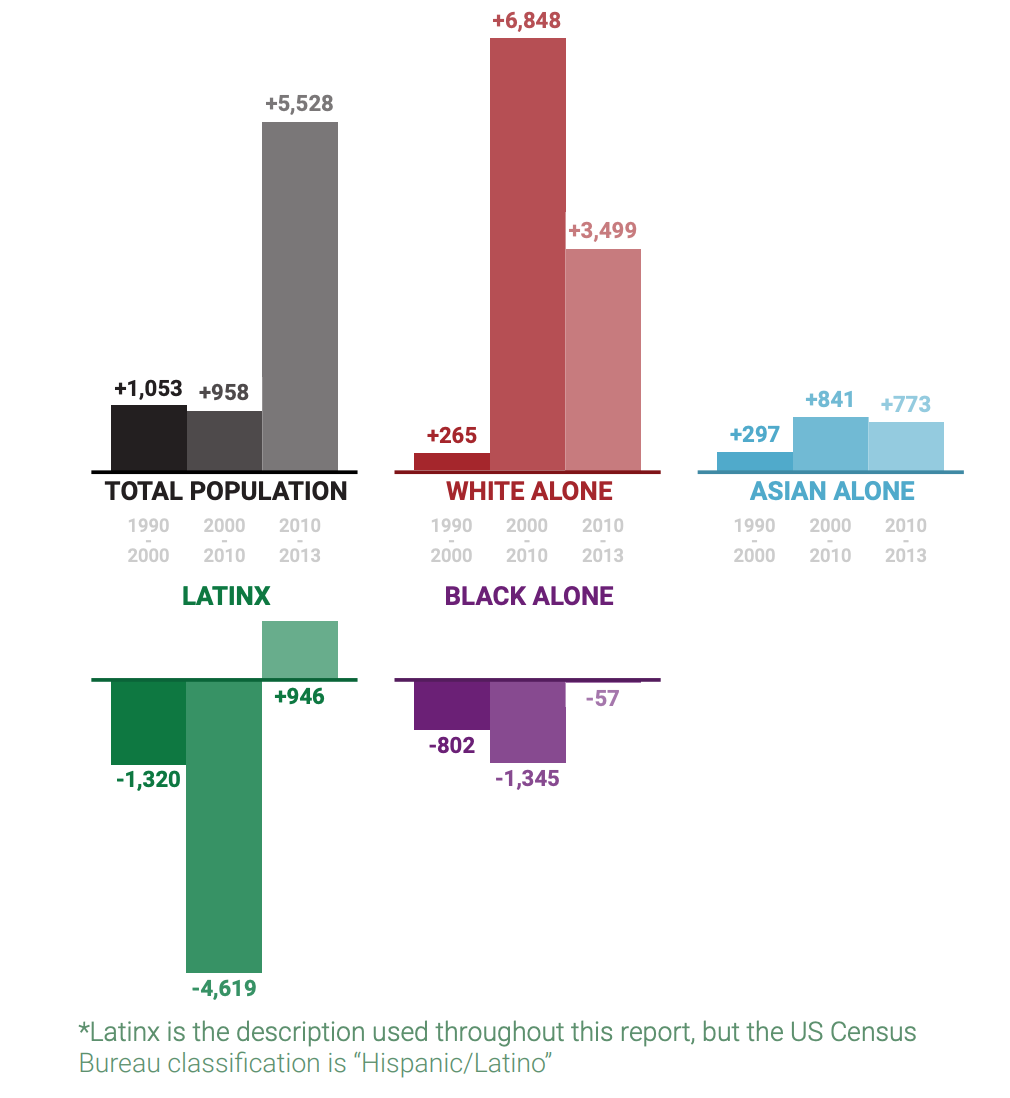

- Decrease of about 5,000 Black and Latinx residents in Park Slope between 2000 and 2013 despite overall population growth of over 6,000 during the same period.

- Loss of over 5 million square feet of industrial/manufacturing space in Greenpoint & Williamsburg.

- Loss of 942 rent-stabilized units in Greenpoint & Williamsburg and 1,470 such units in Park Slope.

To recap, in 2005, in an effort to create housing the city rezoned the Williamsburg-Greenpoint waterfront. The study claims “the City implemented a plan that led to the development of numerous high-rise luxury condos along the waterfront that created physical and psychological barriers between existing residents and public space located along the waterfront.”

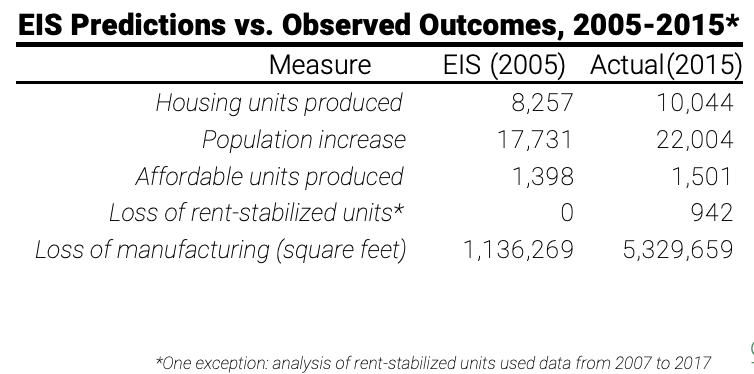

All rezonings require the City to complete an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) looking at the potential impacts of the rezoning. According to the study, the EIS predictions differed greatly from the actual outcomes.

The EIS underestimated everything.

- Population in Community District 1, which Williamsburg and Greenpoint are a part of, grew by 22,000 rather than 17,800 people

- The city expected just over 8,000 units of housing to be produced. Over 10,000 were produced by 2015.

- Five times more manufacturing space was lost than predicted (over 5M square feet lost)

- There was a net loss of affordable housing

“The fact that so many rent-stabilized units were lost after the rezoning is deeply concerning, especially since rents in older, rent-stabilized units are almost always lower than those in new 80/20 buildings or under subsidy programs like 421a,” the study noted. “By our estimates, nearly 900 of the 1,501 rent-stabilized units created were under the 421a program.”

With these numbers also came a racial impact. While the populations of communities of color decreased, the population of white people increased significantly in Community District 1. The study acknowledges that even though there were already demographic changes being experienced in Williamsburg and Greenpoint – Latinx population decreasing from 1990-2000 – the number increased as a result of the rezoning. From 2000 to 2010, the Latinx population went from 61,262 people to 47,008 – a loss of 14,254 people. At the same time, however, 13,000 new residents moved into the district. The majority of them were white.

If someone spends more than 30% of their household income on rent, they are considered rent-burdened. From 2010 to 2015, the number of rent-burdened households in the study area decreased when “large numbers of affluent, white families moved in,” to the mostly luxury housing units. In the southern part of Williamsburg, the number of rent-burdened households increased a bit: “Many of these census tracts still have large numbers of Latinx residents and the increased rent burden may be driven by increased real estate pressure driven by the affluent, white residents moving into the area,” the study states.

The study also notes that the incentives to de-rent-stabilize existing units increased as the housing density increased throughout the neighborhood.

“The loss of historically affordable housing units directly links to the issue of racialized displacement as many residents of color were forced out of older stabilized units and unable to afford the much higher rents in the newly created ‘affordable’ units. It is no coincidence that as these units were lost, the racial/ethnic makeup of the neighborhood changed drastically.”

In 2018, we reported that during the rezoning in 2005, the Department of City Planning (DCP) had loosened the restrictive guidelines for waterfront design, to allow for more design-forward construction and creativity during the development of the public access portions of the miles-long waterfront, which runs from the Navy Yard to Newtown Creek. Back in 2018, representatives from the Department of City Planning (DCP) met with residents in Greenpoint to explain the process of waterfront zoning with a presentation. It turned out, many residents weren’t so happy with the results and felt they were a shortcoming.

Residents at that meeting said they were getting shortchanged with the designs being implemented. Instead of kayak launches or shoreline interaction between pedestrians and the water, the bare minimum bulkhead walls and railings are going up above the East River, while the seating, pathways, and plantings pale in comparison to other waterfront design, we reported then.

Low-income residents are fighting what they call “unaffordable” housing. Currently, Mayor de Blasio’s Housing New York 2.0 plan creates twice as many units for households who can afford rents above $2,500, than for those who are homeless. The House Our Future NY campaign called on the Mayor to set aside 30,000 units of his housing plan for homeless New Yorkers, including 24,000 of these units to be created through new construction. The Mayor’s Plan expects at least 300,000 affordable units to be built by 2026. But, people argue that this sort of “affordable” housing is what drives communities of color out.

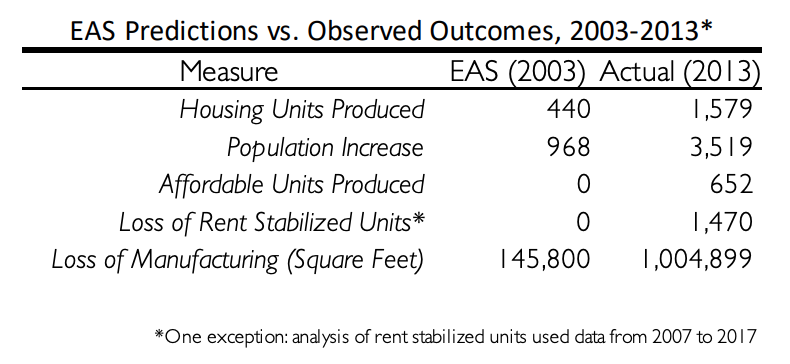

It’s what happened with the Park Slope rezoning as well.

For the 2003 Park Slope and 4th Avenue rezoning, the City ultimately wanted to emulate Manhattan’s Park Avenue to allow for more housing density along 4th Avenue. But, like with the Williamsburg and Greenpoint rezoning, while lots more housing was created, there was similarly a loss of affordable housing units and displacement of the Latinx community. “The Park Slope rezoning area lost an estimated 1,470 units of rent-stabilized housing from 2007 to 2017. Over that same time period, 652 units were added that received some sort of tax subsidy that requires rent-stabilization. Even with these newly added rent-stabilized units, the net loss was still over 800 units.”

While the neighborhood was already experiencing demographic changes prior to the rezoning, these changes were accelerated by the rezoning. For example, the western portion along 4th Avenue was already seeing rent increases and displacement. And from 1990 to 2000, the number of Black and Latinx populations had already been decreasing.

“Unfortunately, this trend accelerated after the 2003 rezoning. Between 2000 and 2010, the Latinx population decreased by over 30%, from 15,278 residents down to 10,659 residents. The Black population also decreased over 20% over this time period, from 6,086 down to 4,741 residents.”

At the same time, the overall population increased by 1,000 residents. The study notes that the white population drove this growth. While communities of color were being displaced, white people were coming into the neighborhood.

According to the study, the rezoning also affected small businesses, though not directly causing them to be displaced. And it had to do with liquor licenses that were given out.

“From discussions with community activists and organizations, while doing research for this report, one of the indicators of neighborhood change we looked at was the change in liquor licenses issued,” the study stated. “Places with large increases in liquor licenses issued could indicate a shift away from locally-owned shops and community spaces to a greater number of bars and restaurants that aim to cater to affluent, incoming residents.”

Though the effects of the Williamsburg/Greenpoint and Park Slope rezoning will linger for a long time, the study hopes to make sure that for future rezoning, something similar does not happen again. For that, the Churches Unites for Fair Housing has created some guidelines:

- Require a Racial Impact Study as part of the Environmental Review process for all future neighborhood rezonings. Specifically, this analysis should look at how environmental impacts are distributed across racial/ethnic groups to better anticipate how rezonings might lead to disparate impacts along racial/ethnic lines.

- Prioritize the retention of communities of color by reinvesting in permanently, deeply affordable housing in areas that are being identified as possible areas to add housing capacity.

- Develop a low-income housing strategy and identify how it will affect the future racial demographics of the neighborhood.

- Identify affluent neighborhoods where mixed-income housing can provide increased access to low-income New Yorkers.

“Given these shortcomings of the current process and the fact that it results in the widespread displacement of Black and Latinx residents, the City must make changes to the rezoning process going forward,” the study notes. “In particular, there needs to be more accurate anticipation of the effects of the proposed neighborhood rezonings, particularly given the history of zoning and its historical impact on housing segregation in New York City.”