Landmarks Commission Votes to Preserve Downtown Brooklyn Home With Abolitionist History

The city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) voted unanimously on Tuesday morning to preserve the building at 227 Duffield Street. The building, known as the Harriett and Thomas Truesdell House for its longtime owners, has historical ties to the nation’s anti-slavery movement but was at risk of being demolished.

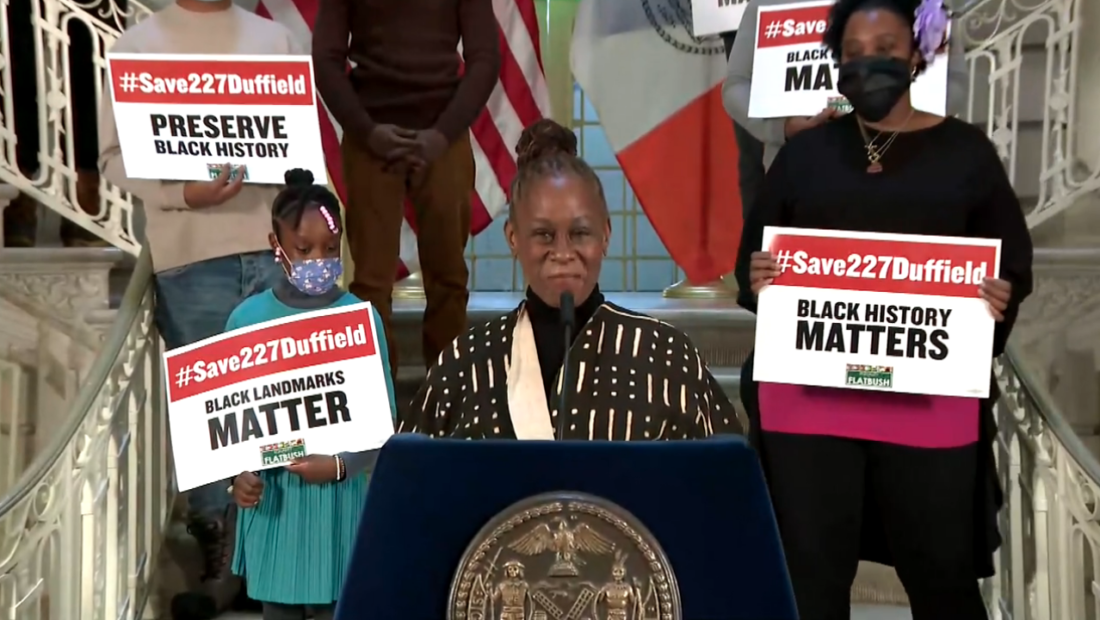

The vote was a major win for the preservatists and racial justice activists who had pushed for years for landmark status. The fight also drew the attention of Mayor Bill de Blasio and first lady Chirlane McCray, who celebrated the vote at a press event Tuesday while flanked by activists holding signs that said “Black Landmarks Matter.”

“We have to own our history,” McCray said at the event. “We have to go back and understand it. It’s on us to give it value.”

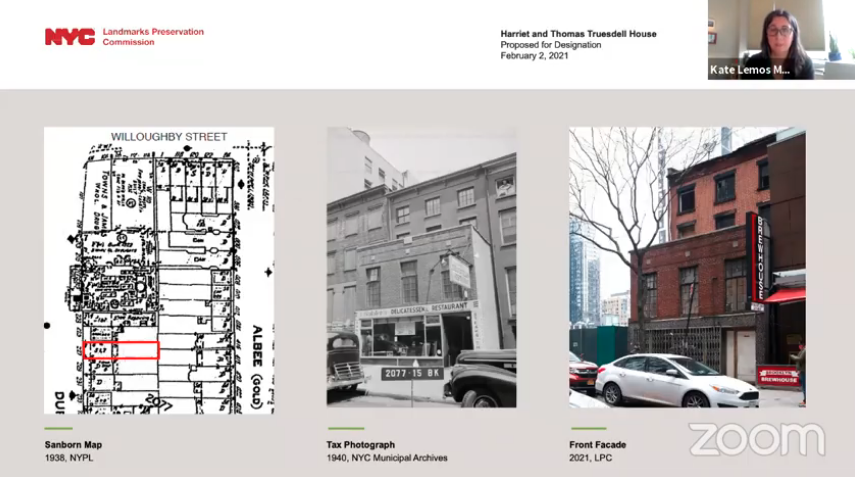

The Greek revival-style row house at 227 Duffield Street was constructed sometime between 1848 and 1851. The Truesdells were active in the abolitionist movement for decades, and helped create several anti-slavery activist organizations in Rhode Island before moving to Brooklyn in 1838. They lived first in Brooklyn Heights, then moved to the Duffield Street house in 1851, where they lived for 12 years.

While there, the Truesdells were associated with organizations like the American Anti-Slavery Society and the National Anti-Slavery Standard, and attended abolitionist speeches and rallies. They also maintained a long friendship with prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.

Harriett died in 1862 and Thomas moved to New Jersey the following year, but the family retained ownership of the house until 1921, a period of over 70 years. In 1933, a two-story commercial addition was constructed at the front of the building, but the original building facade remains visible.

“While its neighborhood has changed dramatically and its lower stories have been altered, the building conveys its 19th century residential character and its significant association with Brooklyn’s prominent role in the anti-slavery movement before the civil war,” Kate Lemos McHale, the LPC’s Deputy Director of Research, said at the Commission’s hearing on Tuesday.

The building’s journey to landmark status was long and contentious. The city attempted to acquire 227 Duffield via eminent domain as part of a 2004 redevelopment plan, but the effort was stymied by a lawsuit from the group Families United for Racial and Economic Equality and Joy Chatel, who owned the building at the time.

Chatel believed that the house was part of the Underground Railroad, pointing to a series of tunnels in the basement that connected to neighboring buildings. LPC researchers were unable to find conclusive proof of that theory, though Lemos McHale pointed out that verifying the existence of such secret passageways was often difficult.

In September 2007, Duffield Street between Willoughby and Fulton Streets was renamed Abolitionist Place. At that point, 227 Duffield remained the only original building on the block.

Chatal passed away in 2014. The building’s current owner, Samiel Hanasab, filed for permits to demolish the building in Jun 2019, and announced plans to build a 13-story mixed use building with 21 apartments and an African-American history museum.

“I have a high respect for African Americans,” Hanasab told Gothamist in August 2019. “This project will be in the basement.”

The pending demolition prompted outcry from local advocates, who created an online petition to save the building that garnered over 17,000 signatures and pushed the LPC to calendar the building for landmark consideration.

Hanasab hung up on a call from Bklyner requesting comment on the LPC’s decision, which prevents him from demolishing the building.

At Tuesday’s press event, activists celebrated the victory, and placed it in the broader context of a fight to preserve Black history.

“This is a victory for every freedom fighter that led our people through the swamps,” said Imani Henry from the group Equality for Flatbush. “That played a role as a conductor on the underground railroad. That risked their lives to shield and hold and keep black people safe on our journey to freedom.”