Brooklyn’s First 24 Hour Diner Still Going Strong Six Decades Later

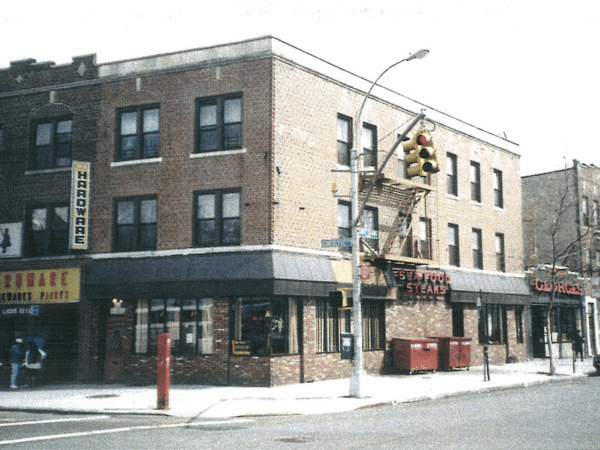

DITMAS PARK: George’s Diner on Coney Island Avenue is legendary. It was the first in Brooklyn to open 24 hours. And at a time when we seem to be reporting on the closure of one old-school diner after another, George’s is making a remarkable comeback.

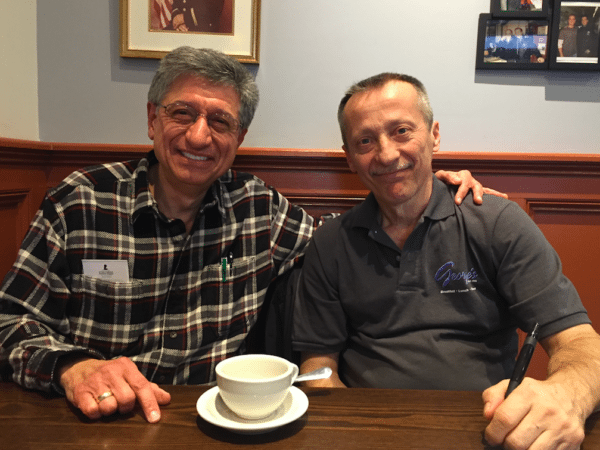

What turns out to be a bottomless cup of exceptional diner coffee appears before me, as I sit down to a table at George’s Restaurant, 753 Coney Island Avenue, with two of the owner-manager-cousins – Peter Harry Montauredes and Michael Papazaharias (the third cousin – Pete Papazaharias – is off today). It’s all in the family, and here is their story.

So, who was there at the beginning?

“It was 1956,” replies Peter, clean-shaven and comfortable in plaid flannel, a notepad and ballpoints in his breast pocket. He owns not just George’s, but the affable demeanor of the restaurateur that immediately puts everyone who enters, at ease.

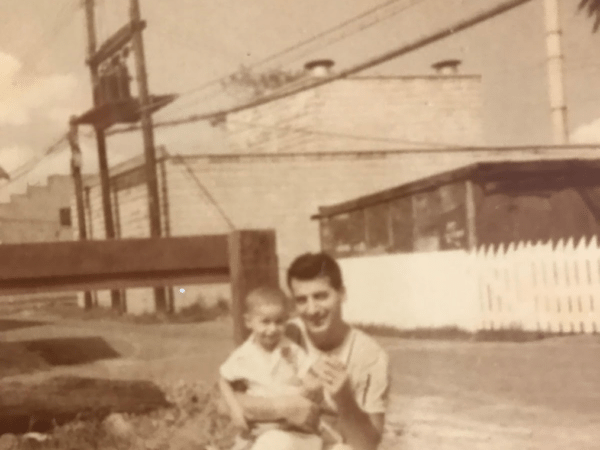

“My parents, Mary and Harry, my grandfather and my two uncles, Billy and Chris. Even me. Five years old, but I was here, too.”

“My father was in the baking business, and my father’s father was a baker – he actually had a few bakeries in St. Albans, Queens. And he had three brothers, and they were all there too. Way back we all came from Greece.

Now, my grandfather here in Brooklyn was my Mom’s dad. He wasn’t a baker, but he was a great guy. He embraced my father like he was his own son. They had a luncheonette further down Coney Island Avenue. My grandfather’s brother owned this building.”

My grandfather got a hold of my father and said: ‘Harry, come to Brooklyn,’ and he did.”

They settled on East 9th Street with my grandparents, two blocks away. Borrowed all the money they could, and opened George’s Restaurant. “They borrowed it all,” laughs Peter, “but they made it back quick, within a year.” American Dream, Greek-American style.

Who’s George?

“George was my grandfather’s brother, who was the landlord, so they named the place George’s, after him, to keep the rent down.” Truth.

George’s began as a hole-in-the-wall, half its current size. But it grew — in its 1980s heyday, during the 1980s, George’s Diner to wrap around the corner to Cortelyou Road.

“When my father started, really it was just a candy store, a luncheonette. Then, when he started baking around midnight, the cops and cab drivers would come up to the window and tap, because they saw the windows steamed up and they wanted to know what was going on.

So he opened the door and he said ‘Come on in, take whatever you want! Look at the menu. Here’s a malted container. Put the money in the container. I’m going back to work.’ And from that day it never closed. And then they took over the store next door, and remodeled the whole thing.”

The clientele back then?

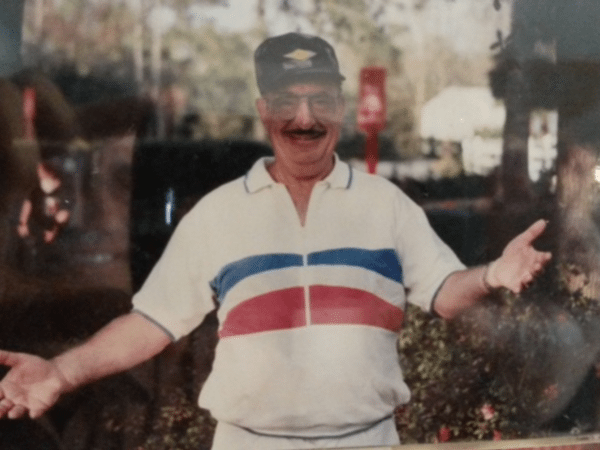

“Everyone!” Peter throws open his arms in a gesture that embraces the unpredictability of an establishment where all walks of life can, well, just walk in, at all hours…

“People on their way to work. Construction. Policemen. Firemen. The policemen were all around-the-clock and this was their go-to place for a cup of coffee,” Peter explains.

“And nurses, on their way to Brookdale. We’ve had a lot of healthcare here, over the years, and cab drivers…”

“And the lunchtime crowd?” I ask.

“A lot of teachers. A lot of the kids. They used to drive my mother crazy! The kids still come back, except they’re collecting social security now. They go ‘Where’s Mary?’”

“So you probably still get the cops.”

“Yes, the cops come. The police station hasn’t moved, it’s still on Lawrence.

“Did you have a soda fountain?” I ask, nostalgic for a Brooklyn I never knew… “Oh yes, egg creams galore! A thing of the past! The soda fountain was right in the front, where that sign is. It was a different layout.”

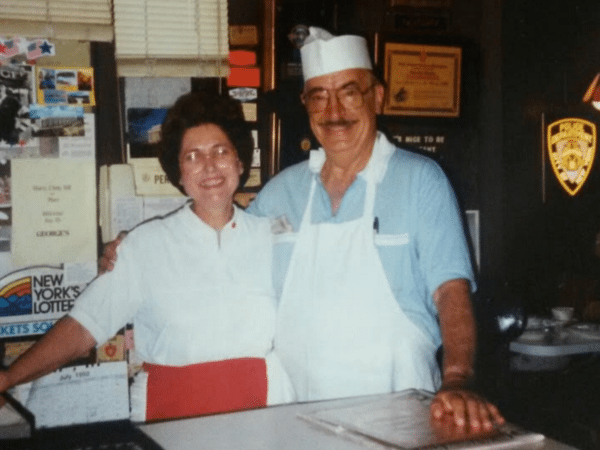

The Queen of George’s

“My mother, The Queen of George’s, she was at the register. And my uncles and myself in later years,” says Peter. “Really. That was her nickname. Her other nickname was Mrs. Clean.

This was our home. Actually, our house was in Rosedale, Queens, but who had time to live there? We were living here, with my grandmother, on East 9th Street.

I went to school [P.S. 139] around the corner. I would wake up. My mother was here in the restaurant, and one of my aunts would take me to school around the corner. This I remember vividly because I always wanted to get back here.

When they let us out for recess in the schoolyard, I knew where the restaurant was. One day, I walked down to Coney Island Avenue, made a left turn and went right into the kitchen. So my father said: ‘What are you doing here?’ I said: ‘I wanted to come and see you.” He said: ‘Okay,’ and took a milk crate, turned it upside down, gave me a potato peeler and some potatoes and said: ‘Go ahead.’ And I did. And my aunts went to pick me up, but I wasn’t at dismissal, so they came here and asked ‘Where’s Peter?’ and dad says ‘He’s here.’”

“And that became a regular thing?” I’m incredulous. “For as long as I could get away with it.”

What did you bake back then?

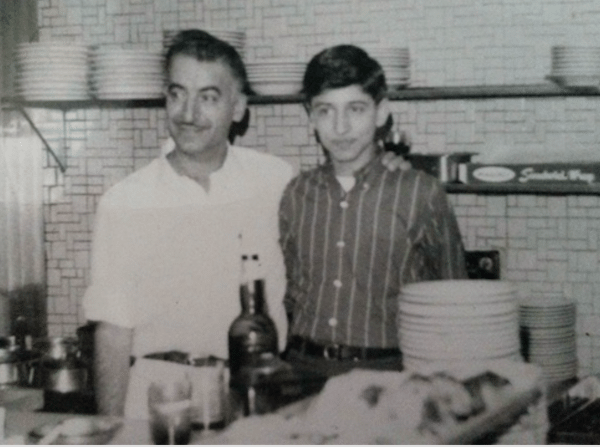

“Oh, everything! My father baked Linzer tarts, French crullers… I don’t know if Brooklyn knew what a Linzer tart was in 1956. Crumb cake, apple crumb pie, blueberry, muffins, corn muffins, bran muffins, you name it! It was all done by his own two hands. My father was the chef and the baker for the first 20 years.

Then his brothers Alex and George, who both owned their own bakeries in Rosedale, took over the baking from my father. My two uncles Chris and Billy also did a lot of work around here, rotating around the griddle, because it was 24 hours then…”

The-city-that-never-sleeps included Flatbush in the ‘50s. “They put their heart and soul into it in those years,” observes Michael, “They got it going.”

“You know, this place was a beacon,” Peter stresses. “When the lights went out in the sixties, George’s was the only place that had lights.” There was a blackout on November 9, 1965.] “You had a generator?” I ask.

“No. It was a fluke. We were on a line from New Jersey. There was a blackout. WMCA announced: ‘There’s lights at George’s Restaurant at 753 Coney Island Avenue. It was pitch black. All the networks came here to broadcast.”

“You’re still 24-hours, right?”

“Well, they’re gearing up for it,” Peter corrects me. “They’re still sleeping at night for the time being.”

“Okay, let’s rewind,” I say. “So you started 61 years ago, 24 hours.”

“Right.”

“ How long did that continue, that you were an all-night diner?”

“Until 2014, but after we lost my father in 1992, it was a different thing,” says Peter, a bit wistful.

“When my father passed, and my mom and uncles decided that the time came to part with the operation, the new people wanted to take the sign down. But the customers got up, and they went outside and they almost knocked the guy off the ladder.

They said: “This is OUR restaurant and THIS restaurant belongs to THIS neighborhood and we’re keeping that name GEORGE’S up there!” And the new owners got down off that ladder and they did a DBA (doing business as). The customers wouldn’t let them change it,” says Peter proudly, yet humbly too.

“I couldn’t come into the restaurant for a long time. My uncles got older, my mother got older, we didn’t know what to do. So I suggested — why don’t we bring it back to the way it started, small?”

It’s good to have cousins.

Peter Papazaharias, Peter Montauredes, and Michael Papazaharias are cousins. Well, distant cousins, and they are now jointly running George’s. “You know, these guys worked here when they were teenagers. Michael and Pete. They’re two first cousins. And they’re cousins-of-my-cousins.”

Michael works front of the house at George’s almost every day, Pete runs the kitchen. A neat, soft-spoken fellow in a polo shirt, with a buzz cut and trim mustache, alights in the seat opposite me. “My cousin Michael!” Peter presents his blood proudly. “Hello. Can I get you more coffee?” Michael asks me, humble and accommodating.

Turning around George’s

“So my brother-in-law Steve Athanasakos had Jimmy’s Luncheonette on Church Avenue. He knew I was determined to put this place back on track. So one day in 2014, he bumps into Michael and Peter in a diner where they were working…”

Michael returns with my cup, refilled to the brim. It lands with a satisfying “clink” in its saucer. “Thank you, Michael,” I say, tipping the pitcher of cream into my cup.

“We met at the El Greco, the cousins realized what I wanted to do here, and then they remembered working here as kids, as bus boys, when the place ran all the way down to the corner, we just picked up like long lost family…”

Cousin Pete had just sold his place. He wanted something smaller. The timing was perfect. “Michael and Pete got the whole thing going again!” agrees Peter. “I was determined to put George’s back on the right track with the right team to continue our families’ legacy and good name, serving fine, clean and lean food to our great Brooklynites!”

Where does the Greek Diner tradition start?

“It didn’t start in Greece, that’s for sure,” laughs Peter. “When people came here they needed a job that doesn’t require a lot of English,” explains Michael. “So to wash dishes, you don’t have to talk to nobody.”

“You begin to learn a little English and you become a bus boy or a waiter and then you see the concept, how the operation goes, and you say ‘Ahh… I can do that too!’ So you buy a restaurant.”

“Even before, the Jewish people used to own the restaurants, like Dubrows on Kings Highway, and so many other places. They were the first immigrants here,” says Michael, “before everybody else, when they were chased from Europe and all over the world.”

Why do you think diners close?

“The cost of operating,” says Michael, “because don’t forget, in those days the waiter used to get a dollar an hour, today they get $7.50. Next year’s it’s going to be even more. Also, real estate values going up, and owners getting older, with no one in the next generation wanting to take over…”

“The El Greco closed, Bernie’s Closed, the Sea View closed, the Sheepshead Bay Diner closed… and on 86th Street the Vegas Diner closed, the Plaza too…The Tiffany is gone, I think. They’re all gone. George’s is still here.” Peter turns to the cousin-of-his-cousins: “I even think the Foursome closed recently, did it?” “Yea,” replies Michael.

Who’s left? “The 3 Stars, the Mirage on Kings Highway, Perry’s Diner on Nostrand Avenue, then about five blocks away is Kouros Bay Diner, also on Nostrand Avenue, and the Floridian, on Flatbush at Fillmore.”

“But you know, the owners of diners that closed weren’t hands on any more,” observes Peter. “These guys here are hands on. Our other cousin Pete, in the kitchen, and Michael, they handle everything themselves. I mean, you can delegate to a point, but if you’re hands on, you know, it’s a little different.

George’s Way

I take in the cheerful room, which faces a western sky. There are eleven sturdy tables that don’t need saucers to level them to the floor, and an inviting counter running front to back. The robin’s egg blue walls, lined with photographs, showcase generations in white aprons and local dignitaries in power ties of primary colors.

“Do you get many politicians?” I ask.

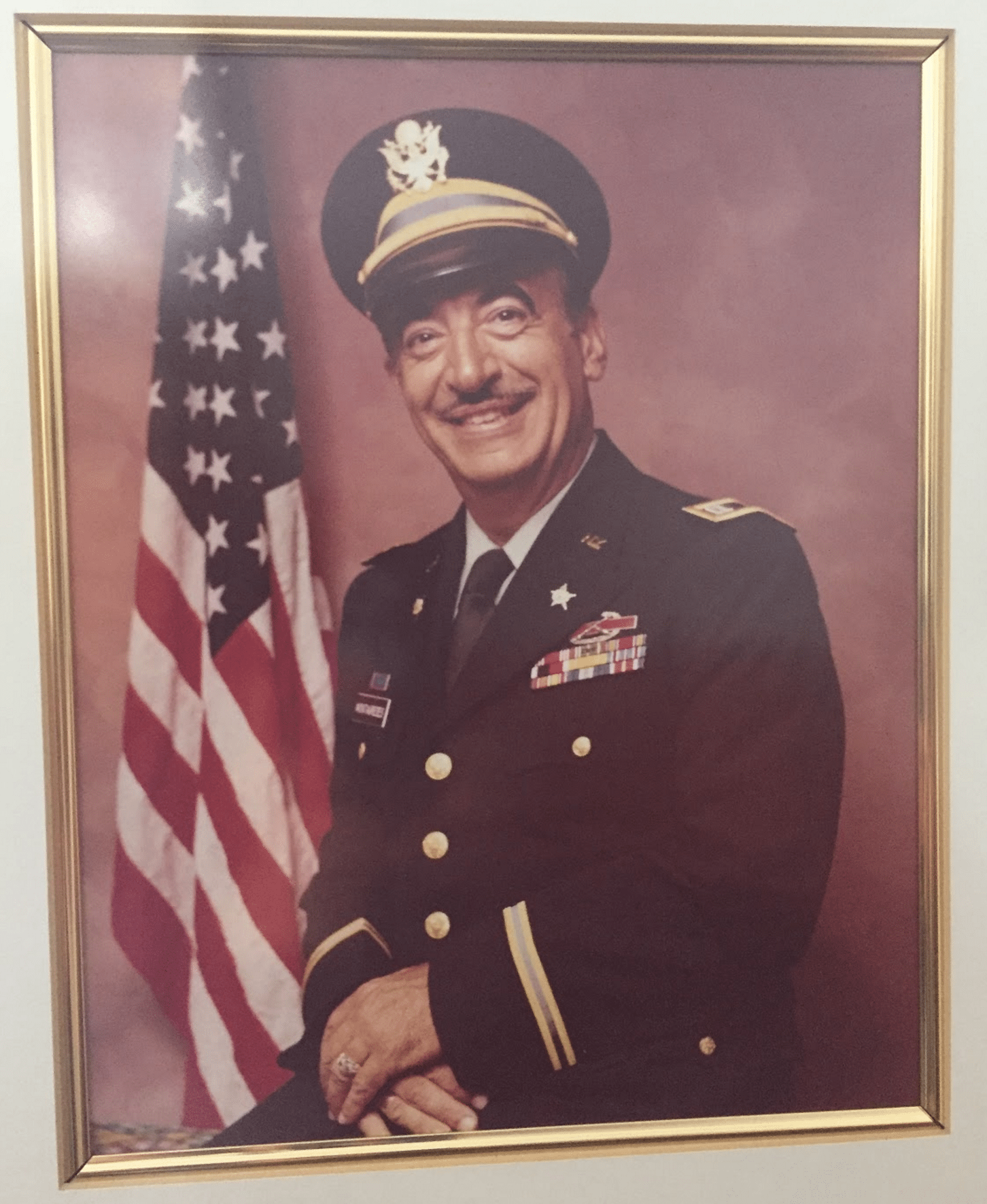

“All of them!” answers Peter. “Marty Markowitz was a fixture here. He’s Mr. Brooklyn. He’s not the BP anymore but he’ll always be Mr. Brooklyn,” affirms Peter. He called my dad, The Patriarch.”

Back in April Councilman Matthieu Eugene held a ceremony in honor of Mary Montauredes, who had recently passed, and where they dedicated a City Council Citation to George’s.

“She did know about the citation,” Peter says. “They renamed this section of Coney Island Avenue George’s Way, for my dad’s World War II service in the 63rd Infantry Division. He got back in ‘45 or ‘46.”

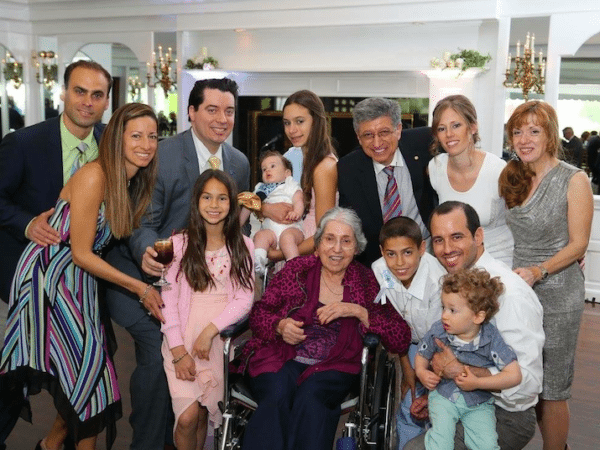

“You have children?”

“Yes! three children, five grandchildren, and my beautiful wife Paula of 45 years, who I also met in George’s!”

“Any of them interested in this business?”

“They all are, to some extent, but they went in other directions.”

Did you ever consider another direction, Peter?

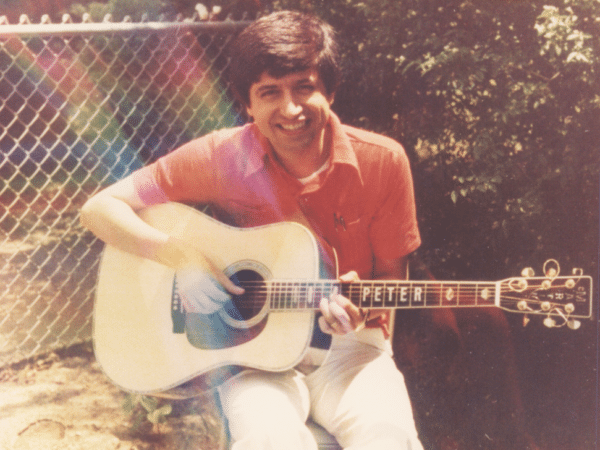

“Yes, as a professional musician. Back in ‘69 I went to the Berklee Conservatory of Music in Boston and was doing well, but I couldn’t tolerate the drug culture. The ‘60s was a very troubled time in our country, both culturally and politically. So it was back to George’s, guitar and all.

Our family, like many others, tried to make a difference back in the sixties, even before that.

Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne and Jackie Robinson all lived in St. Albans, not far from my grandfather’s bakery. In that time of segregation, my grandfather would invite them to the front of the line, give them whatever they wanted: coffee cake, muffins—Satchmo loved cinnamon rolls.

/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Record_0008-2.wav

Anyway, we keep the faith and the beat goes on… My civil rights songs got recognition at the Woodstock Square & Playhouse, some standing ovations on the Jersey shore back in ‘68 and ‘69, in the shadow of the folk rock world.”

Do you envision ever expanding again? Would the demand be there?

Peter noodles this one, “Will the energy be there?”

“Sure we have the energy!” jumps in Michael. “But let’s see how things develop. I dunno, these people still have a lease next door. Maybe another year or two?”

Clientele Now

“We’ve got everyone. We get the nanny crowd, during the daytime, there’s a lot of them. Law and Order used to rent the whole store for a while, but not lately. The bar [Highbury] stays open until four. Saturday and Sunday mornings,” Michael whispers, “they wait at the door for us to open.”

“Do you know how many people come in and say: ‘This place makes me feel so good!’” asks Michael. “One day there was a party of four. When they got up to leave they said, ‘Thank you for opening today because there was no other place to have a meal.’ People are very, very thankful.” And this is how Michael crushes it with his 18-hour-days.

He notices my cup, empty again. “You want one more?”

Ahhh… nothing like a homey coffee served in a chunky cup. Top notes, bottom notes. Who cares? It satisfies.

While some of the baking is still done on premises, most of the baking is outsourced. “Muffins we do in the morning, sometimes danishes,” offers Michael. “A lot we get from the Bay Ridge Bakery, which is one of the best suppliers.” “They’re family also; we’re also related,” interjects Peter. “We can put in an order for French crullers and jelly donuts. And the Linzer tarts,” Peter chuckles.

Menu Now

A platter of golden steak fries sails by, eye level. George’s clearly meets high standards for starchy foods, but we have to get into the real test: soup.

Every diner worth its salt makes a daily soup from scratch—seven soups for seven days. A cycle of soups is critical to customers, reassuring in its repetitiveness, consoling as consomme.

“Yea, every day there’s a soup,” says Michael. “The only standard soup is chicken noodle. Sometimes we make that with bowtie pasta. Monday we have Yankee bean, Tuesday we have lentil, Wednesday we have minestrone, Thursday we have split pea, Friday we have New England clam chowder, and Saturday we have potato, kale, and vegetables. And cream of turkey on Sunday.”

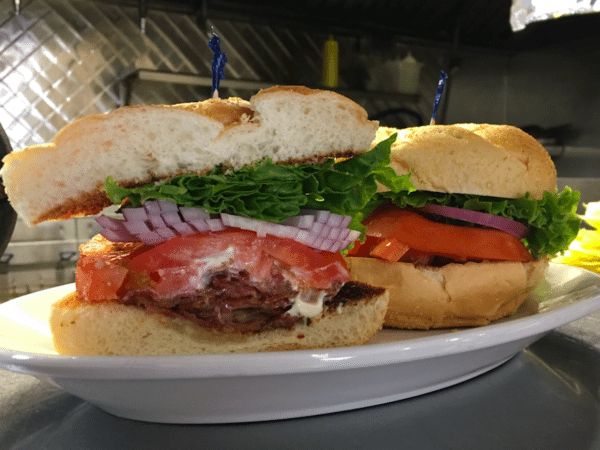

What’s the top seller?

“I would say burger deluxe,” Michael replies. “Also, souvlaki platter and spinach pie.”

“The key to the spinach pie is to wash it. Real good,” asserts Peter. “And then the phyllo has to be right,” adds Michael thoughtfully. “Some places, they make it too thick, like ¾.” It’s not supposed to be like that. The bottom gets soggy that way.”

“You sure you won’t have anything to eat?” Peter says, sliding the menu my way.

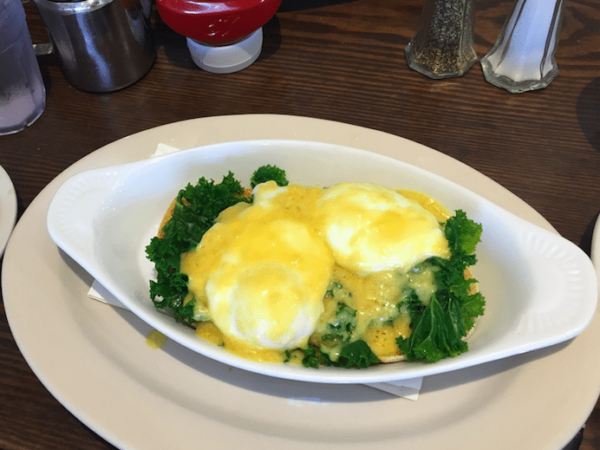

“Eggs Benedict with kale?” I remark. “Daring! I’ll try that. Can I have it on a bialy instead of English muffin?” “Sure, why not? We’ll call it The Maria,” proclaims Peter. I’ve arrived.

What you feel in George’s is the collective vibration of every heart that’s ever beat under that roof at 753 Coney Island Avenue. Everyone who’s flipped a fried egg, or eaten it, who’s swept crumb cake off their lap or swept crumbs up off the floor, they’re still all here, cooking, cleaning, serving, eating, laughing, connecting over a cup of Vassilaros.

You feel the life force of Mary and Harry, and little Peter, and all the aunts and uncles, teachers, politicians, policemen, firemen, film crews, and nannies, causing a gridlock of strollers. Even the hungover from the Highbury, they’re here too, reluctant to leave, like me.

I stand to leave. “Oh, and you better put Harry’s cheesecake in your story somewhere too,” Peter calls after me, “or he may hit me with a lightning bolt from Heaven!”

“Cheesecake,” I say. “Got it.”