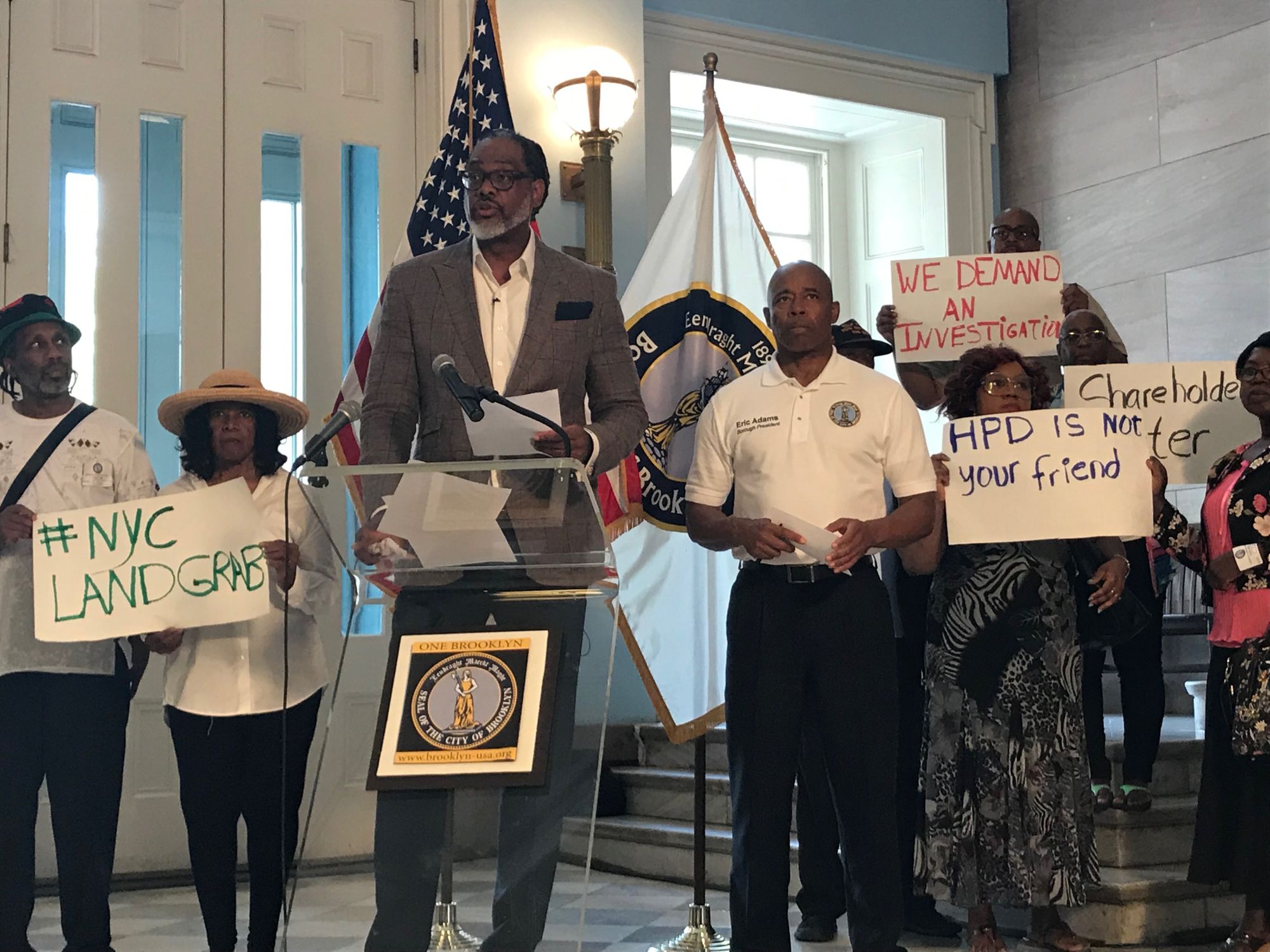

Borough President Adams Calls Third Party Transfer Program ‘Racist’

BOROUGH Hall — Borough President Eric Adams on Thursday said the city housing agency’s implementation of a controversial property transfer program is “racist,” and that its practice of taking homes away from black and brown homeowners is “intentional.”

“What they’re doing to black and brown property owners is malfeasant at best,” he said at a press conference at Borough Hall. “There is a clear conspiracy to remove homes from black and brown people, and we need to call it the way it is and not try to sugarcoat it.”

“This unbelievable that this is happening,” he added, lamenting the “overly broad application” of what he said was a fundamentally well-intentioned program.

“We are committed to fully reviewing the program through our collaborative working group with Council Member Cornegy,” Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) spokesperson Juliet Pierre-Antoine said, without addressing Adams’ accusations of city-sanctioned racism. “We ultimately hope to improve the transparency and effectiveness of the process while doing all we can to assist building owners with addressing arrears and avoiding escalation of financial strains or physical distress.”

Third Party Transfer Program allows the city to transfer property with municipal debts like property taxes and water bills, as well as properties with city-identified hazardous conditions, to non-profit and affordable housing developers. The program was created by the City Council in 1996 in response to decades property abandonment and the city’s failure as a landlord, and works to ensure troubled properties are in a state of good repair and taxes as well as bills get paid to the city.

Adams’ comments come after Council Member Robert Cornegy, who hosted the press conference, said earlier this week that he would this fall push bills in the housing and buildings committee, which he chairs, to fix the Third Party Transfer Program. The unveiling of potential legislation, first reported on Tuesday by Bklyner, followed a hearing on the program last Monday, when the city’s housing commissioner was put on the hot seat over how the city has carried out TPT.

At that hearing, HPD Commissioner Louise Carroll adamantly denied claims that the city was targeting homes owned by people of color for third-party transfers.

“Council member, when we do the selections, we are not looking at racial data. All we are looking at it how much money is owed to the city,” she said at last week’s hearing. “TPT does not target any specific neighborhood or community. It selects properties through a thoughtful process grounded in local law and focused on tax enforcement and rehabilitation for residential properties with municipal arrears.”

And, notably, many of the neighborhoods where properties have been selected for the controversial program the had been redlined and disinvested from, bringing structural, historical factors that predate, and reach beyond the scope of, TPT into the equation.

Cornegy remains unconvinced.

“I was unimpressed with the city’s response to our questions, and it’s clear that there’s more work to be done to make sure the Third Party Transfer Program is meeting its intentions in an equitable and fair way,” Cornegy, who represents Bed-Stuy and the northern part of Crown Heights, said Thursday of the hearing. “Given the wide latitude that’s given to HPD on this program— and their targeting of black and brown communities— the program should be subject to a higher level of scrutiny and more Council oversight.”

He went on to cite statistics from a City Council report on TPT that showed a disproportionate amount of properties selected for the program during the latest of ten rounds were in predominantly black neighborhoods in Brooklyn like Bed-Stuy, the northern part of Crown Heights, Stuyvesant Heights, East New York as well as Bushwick.

Specifically, out of the 420 properties selected in the last round, which had a total value of about $315 million, 46 percent of those selected were in Brooklyn. Thirty-two of them were in Crown Heights North, 18 in Stuyvesant Heights, and 17 in Bed-Stuy—neighborhoods that are part of Cornegy’s district.

“District 36 is ground zero for gentrification,” he said, citing rising property values there in recent years.

The report also showed that HPD had strayed from its playbook for selecting properties. According to the report, four properties owed less than the current $1,000 threshold, which would be raised to $100,000 if a Cornegy-proposed bill is passed, and three did not owe any money at all. In addition, the report found that HDFC coops comprised 118 of the properties that the city chose for the latest TPT round, as well as 27 of the 65 properties that ended up being foreclosed on.

“The practical implication of an HDFC’s inclusion in TPT is that the HDFC converts from a cooperative to a rental building post-transfer,” reads the report in part. “This meant that the economically vulnerable New Yorkers who were shareholders in such properties—and may have spent years rehabilitating and maintaining such properties when the city no longer wished to do so—stood to lose ownership of their units as a result of TPT.”

In turn, Cornegy said in the coming months his committee would be workshopping bills to fix “fundamental flaws in the program,” as part of a process that will move forward concurrently with a working group— which was created in June and of which HPD is a member— that’s tasked with reexamining the program and proposing changes to it.

“I’m encouraged that the HPD commissioner has said everything is on the table for the working group,” he said, referring to Carroll’s comments during last week’s hearing. “I’m joining the working group in good faith, [and hope] that we’ll find an equitable and fair solution. I’m optimistic about that.”