Yakhil Yakubov On Uzbekistan, Democracy, And Unclaimed Shoes

It’s rarely a simple transaction when you visit Yakhil Yakobov, the cobbler of Foster Avenue. You don’t just hand him two sawbucks to get your Timberlands resoled, or a five dollar bill for a new watch band. It’s a conversation with Yakhil too.

The store is small. There are usually at least two people ahead of you in line when you enter, making small talk. If there are three, you have to wait outside. I chose a Sunday evening for my interview. Every reasonable cobbler is closed, but not Yakhil Yakobov, he’s open, but less busy.

While you wait on the sidewalk, you window shop—what’s displayed in front of the glass, not behind. Vacuum cleaners, in candy colors, are lined up on the street, slim in the sunlight, like Vegas showgirls. There’s a motorcycle and locked mysteries, poking out from under tarps. Plastic market bags of finished jobs, knotted tightly, with tickets affixed, hang everywhere in festive rows, like holiday garland.

He’s bending over his workbench, in a plaid flannel shirt and latex gloves, wearing a magnifying contraption on his brow that makes him look like he’s been through the disintegrator-integrator transporter in The Fly.

“Where were you born?” I ask.

“In Soviet Union. In Uzbekistan.”

“So you speak Russian and Uzbek?”

“I speak many languages. I speak Farsi.”

“Farsi? Where did you learn Farsi?”

“In that country. They speak different languages: Uzbek language, Farsi language, but most of them speak Russian, too. That’s why in Soviet Union, we spoke mostly the Russian language. Uzbekistan is Muslim.”

“So you’re Muslim?”

“No, Communist. No religion, no mosque, no church, no nothing!”

“So where did you grow up, near the capital?”

“No, in the city of Surxondaryo, near Afghanistan border. When the Soviet Union went into Afghanistan, they got there from my city. 16 years ago.” Yakhil shrugs. “We do the same mistakes now.”

“Did you come here with your family?”

“Yes, in 2000. That’s when it became separate. It’s a small country now. Nothing to do. You can see the people don’t like it, their own country! Same head of government for 25 years, one person. What kind of democracy is that? It’s not democracy.”

I’m incredulous. “So you’ve had the same person in power in Uzbekistan for 25 years?”

“Yes, one president. Only one. In 25 years!”

“The Soviet Union started to dissolve in what year…? ” I ask. Boy, do I need a refresher.

“In 1998, it started, the collapse. After that, a lot of people left. Even before that,1995. After the collapse the president said: ‘Everybody go home!’

“There’s too much corruption. The police, they catch you, check your pockets and cry ‘Terrorist!’ and whatever you have in your pockets, they rob it. I saw, by my own eyes, they robbed! They said ‘Where’d you get this money? 200 dollars! Where is the paperwork for this money?’ What kind of paperwork do you need for this money? It’s not their money. They take it from you anyway.”

Yakhil, hammering at a sole softly, seems resigned.

“Just for this holiday, I sent $2,000 to my family back home, but the banks didn’t give it to them. They told them: ‘We can’t give it to you now. After the holiday, we give it to you. But it was for the holiday, this money. I don’t know when they got it.”

“The bank was closed?” I ask.

“Yes, before the holiday. Big corruption!”

A guy with shoulders too wide for this store enters.

“I’m looking for shoelaces for work boots,” he asks.

“Big boots? Like this?” Yakhil holds his hands a couple of feet apart like he’s holding a pizza box.

“Yea.”

Communication through hand gestures, usually with exaggerated facial expression, this is our universal language.

Yakhil points to a pair on the pegboard: “It’s 45 inches, it’s okay? Black?”

“Brown.”

He frees the right laces and hands them over, “4 dollars.”

“Thank You,” says the guy lumbering out.

“You’re welcome.”

Done. Shortest transaction I’ve watched go down in the shop. While he’s always open to chatting about broken bicycle seats, Bosnia or where to get the best blinis in Brooklyn, Yakhil is also respectful of people’s time. Don’t want to linger and shoot the Shinola? No problem. “Next!

“What were you like as a child?” I wish I had his mother here to ask. I’m imagining her living room rug, strewn with transistor radios and clocks, backs opened and guts spilling over… “Were you curious to see how things worked?”

“No. No. In Soviet Union, when everybody was together in one country, the schools taught us. For girls stitching. For us boys, small furniture, they showed us sharpening, how to use the hammer.”

The bell hanging over the door tinkles. The greengrocer next door enters and wants Yakhill to break a C-note. No problem. This is an all-cash, small-bill business.

“So that’s where you learned how to do basic repairs, in school?”

“In Soviet Union, this was not a bad time. Everything free. Nobody talked about money. When a student went to a factory, the government even paid children small money.”

“So as a child, after school you’d go work in a factory?”

“Yes. They asked: ‘You a student? You want to learn something?’ I applied, and the government paid me money, for learning.”

“Then what Yakhil?”

“After school, when you’re 18 you must go into the army. It’s a big place with different people from different places. If you’re smart, you’re enjoying it. You’re learning many things, this and that, you’re learning weapons. After you leave the army, you’re more smart! In army they said: ‘Who knows how to cook?’ I said: ‘If you want, I try it. You can tell me if it’s good or not?’ They said ‘Okay, go try.’ They said ‘It’s good. ‘Where are you learning this?’ I said: ‘I know this job, from everything cooked at home. My mother, she showed me how many you put it the oil, how many you put it the meat, how many you put the rice. She teached me. They said, ‘Okay, you wanna cook for us? 300 persons.’ So at eighteen-years-old, I cooked for 300 persons in Russian Army!”

“What happened after you fed all those happy soldats in the Russian Army?”

“Well after army, if you have the brain, you do something in business, whatever you want to do. You go to the government, you say you want to open a shoe store, and they say ‘Okay, you want to be a shoemaker? Go to him, he’ll help you. Okay, we open for you a place. Before you start this job, you have to apply.’ It belongs to the government, everything, not by yourself.”

The phone rings. “Allo?”

Yakhil is speaking Russian, I think. He hangs up and turns to me,

“You understand me? Maybe I explain you not in correct English? My English from street.” He laughs.

“Didn’t you learn English in school?” I ask.

“No, in school we spoke German. Sprechen sie Deutsch.”

“So you’ve only been speaking English for 15 years?” I’m impressed. “You’re doing just fine Yakhil.” I can’t fathom what it would be like today, for my middle-aged cerebral cortex to acquire a new alphabet. But that’s just what Yakhil’s did.

“So after the army, at twenty, I went to a photographer. I had learned something with cameras in school. He saw that I knew this job, not exactly, but I knew the darkroom, the small camera. He said, ‘Okay, you can start with me. I show you darkroom. I know almost everything.’ He teached me with bigger camera, studio camera. That’s it. Thirty years, my whole life, I worked in the studio. But more than a photo studio, we had big room for everybody. Everything below the government. I managed this. We had a shoemaker, a watchmaker, we had a barber shop, and a photo studio, also fixing the gold. I could open this store, that store…”

“Was it all under one roof?” I marvel.

“Yea, we didn’t pay rent, nothing.”

“So you managed this big department store of repair?”

“Yea, yea – I put some people together to do this work, and everybody had to pay the government.” He chuckles softly. “People were coming from any place to my city. You know, some people are smart some coming from schools in capital city, from factory, learning digital watches. Old people teach the younger.”

Really? Living with a twelve-year-old who maneuvers his phone like Magellan circumnavigating the Earth, I think it’s just the opposite, young people teach the older.

“Most of the time if you didn’t understand how to do something, older people taught you, or if I knew, I taught someone else. People have to be a little bit smart. In my brain, if you hand something to me, I do it quickly. I catch on quickly.”

I look around and take it all in, Yakhil’s projects from A-Z: belts, bicycle wheels, boots, clocks, coats, handbags, irons, knives, lamps, radios, scissors, sewing machines, shoes, shredders, suitcases, vacuums, trumpets. Even a Cossack’s curved saber. Obviously, Yakhil catches on quickly.

“Let’s talk about this store now. What is the most unusual thing someone has brought you to fix?”

He motions to a computer monitor. “Electronics. They come in and say: ‘Oh, doctor, I need help! I tried to fix it myself. You smart. You try.”

“Did you fix the thing?”

“Yea. Or clothing iron. I know the electric things also. I learned everything. I never say, ‘No, I don’t need to learn that.’ Children have to be interested. I was interested in everything. Children have to be smart doing things with their hands. I had two children here, in the shop. I showed them ‘Look, this is how the watch looks inside. I told them ‘You see the small screw. You have to try to open it.’ Their fingers were not working. ‘Look, this is how you have to hold it.’ They sat 10 minutes and said ‘I don’t like it.’ They weren’t interested. They’re looking on their phones. The phone, the internet, killed the young generation. I think so. They are only smart on their phones. I use a regular phone, to make calls: ‘Hello!’ ‘Bye bye!’ I don’t have time for more.”

What about your own kids?

“They don’t like it either. ‘Shoemaker! They say, ‘this is bad name. What is this?’ They don’t want it. My son, he’s a mechanic for cell phones. He doesn’t like this kind of job. It’s a dirty job.

And sometimes Sundays, I’m also open, because I need to take care of the people.”

True. Whenever I pass by, the gate is up. “You open seven days a week?”

“No six.”

“Except some Sundays,” I argue, “like this one.”

“From 8 to 8. I have to work. The people call me the night before ‘Can you meet me in the morning? If you open 10 minutes early, I drop the stuff.’ ‘Okay,’ I say, I do what I have to do.”

“How long have you been at this location, 1221 Foster Avenue?”

“Since 2004.”

“You rent this store?”

“I bought the business from a Russian man, and rent the store space. Before that, Italian people. When the building went up, also the shop was opened, same time. It’s about 90 years old, and the shop was shoe repair.”

“I bought this business, but really I started this job myself.” Yakhil continued. “When you change the owner, people are scared. They don’t know you. You have to make your own customers, at the start.”

“Now they come to me. They pick up the shoes. Nobody checks my work. They trust me. ‘I know your job,’ they say. ‘That’s it. I don’t need to see.’”

“That must be satisfying, Yakhil, that level of customer trust.”

“They trust me. Any problem, I’m here. And then I try to work with good stuff only. Not the cheap stuff. I want to fix it one time only, and that’s it.”

While Yakhil’s repair projects pack the walls, counter tops and workbench, I see that above eye level too, any unoccupied space is an affront to Yakhil’s vision. It’s an art gallery. The four walls, convening at the tin ceiling are crammed with curios and purring clocks, pendulums wagging gaily. Welcome to a Swiss tourist trap.

“Why do you have so many cuckoo clocks Yakhil? Are they for sale?”

“Yea, but nobody buys. I collect them. People don’t have room at home, so they give them to me, to make a nice store. I say okay, leave it like that. That’s it.”

My eye wanders to a dishy blonde; a full-body nude in needlepoint. Masterful embroidery, she could hang amongst the best medieval tapestries at the Cloisters.

“I like your girlfriend up there,” I smirk.

The cobbler follows my gaze, “She’s expensive, all by hand stitch work. I brought her in to sell. Because at home, who could see her? People say ‘She’s nice, I give you 200 or even 300 dollars for her.’”

“I guess you get more offers on her than on the cuckoo clock,” I say.

“Oh yea, but I changed my mind. She’s not for sale. Just leave her like that. I look up at her. She gives me happy eyes.”

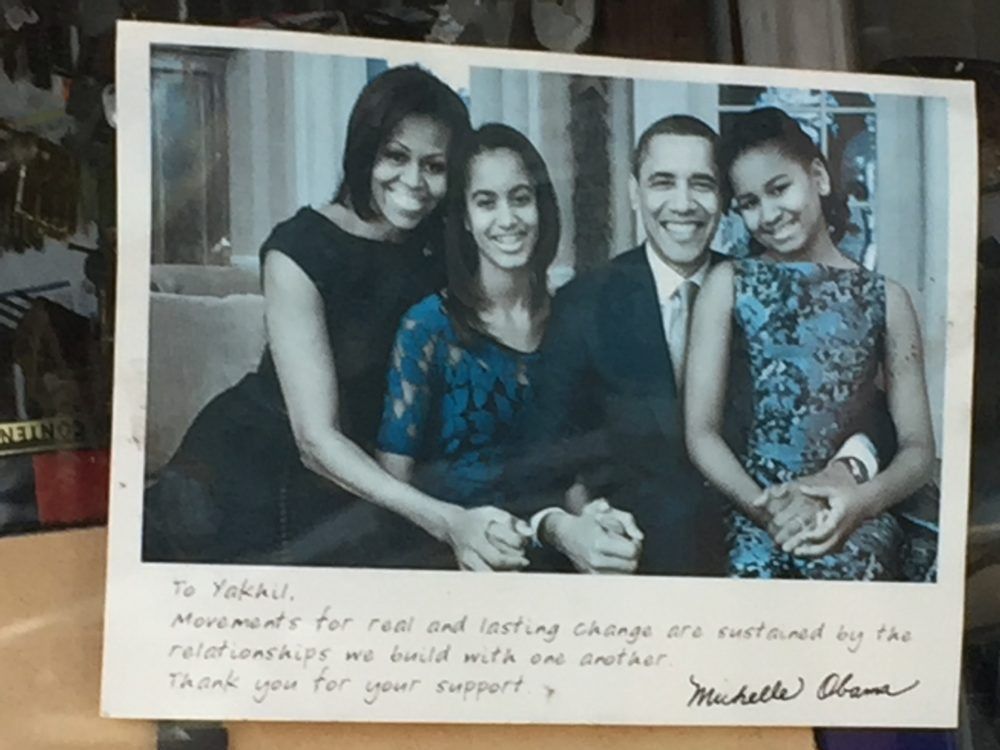

My eyes wander to a picture of the Obamas in the window.

He sees this and offers: “When I got my citizenship, I registered Democrat, in Clinton time. They sent me picture.”

“What do you think of Obama? How’s he doing?”

“I think he’s young. He doesn’t have experience. They put him in without experience. It’s not small job, the presidency.”

I marvel over the distended shopping bags everywhere, round like ornaments, filled with the promise of second life for old shoes. I lean over the counter and whisper the question in the back of my mind since I was old enough to drop off my own ballerina flats for resoling: “So what do you do with shoes people never pick up?”

He doesn’t answer right away. Instead, a smile starts below his nostrils and broadens gradually, in both directions, to his ears.

“I Collect… Collect in basement… You wanna see? About ten years of shoes in basement!

I don’t know how many bags I put there. Some guy came after three years. He was a police officer. He came back after he retired. He bringed his ticket for his work boots. I have many things, the people don’t pick it up. But I can’t sell it because after a while, they coming back…”

“So that’s nice of you,” I reply, but I think: hoarding, imagining a mushroom cellar of stuffed Shoprite bags.

“But what about the stuff that’s over 5 years old, Yakhil? Has anyone come back after 5 years?””

“Yea, yea, there’s some people coming. Some guy from jail came, ten years later. If you want it, I find it! If you have ticket, I have it! I keep the shoes all my life!”

“Ha! You’re a pushover Yakhil. People know you don’t throw anything away. They get lazy, and keep forgetting to come back.”

On second thought, that’s sorta nice, isn’t it? In ten years, species go extinct and polar ice caps melt, but an ex-con still gets his Hush Puppies back. People still matter, over time.

When do the shoes go downstairs anyway, after 3 months?”

“No, 30 days. After that I am not responsible.“Yakhil, would you ever think about putting unclaimed shoes, the really old ones, out on the sidewalk to sell them?”

“No, no, I not sell them! People would try on these shoes, then they would ask ‘You have smaller or bigger size instead?’ It’s a headache! I don’t have time for that.”

“Do you have any shoes downstairs that you’ve had for, say, fifteen years? For as long as you’ve been here?”

He laughs. “My mistake is, I not put the date at first. 5 years ago I started putting the date.”

“Okay, so you know anything downstairs without a date is over five years,” I say. “Yakhil, you should really think about selling the stuff over five years old.”

“No, never!”

I put my bossy on. “On a nice day next spring, we’re gonna have a sale. We’ll put it all out there on a blanket. I’ll help. We’ll make you some money! Enough to buy your family a really good meal in Queens.”

“Maybe I have to do like that…” he softens. “I have good shoes. Brand new. They leave it and they forgot it. They don’t give me phone number, or they mistake their phone number.”

Yakhil is a good old-fashioned handyman. Like a veterinarian is to the field of medicine, treating gerbils to Great Danes, Yakhil is to repairs, fixing stilettos to Singer sewing machines. But some objects that make their way to his workbench have got to stump even him.

“I know you’re close to perfect Yakhil, but what have you ruined? Somebody’s leather coat?”

No response.

I press: “Something didn’t behave the way you thought it would… You were working with a piece of leather… and all of a sudden… Oops! something went wrong! A mistake!”

“No,” he replies.

“Ha!” I laugh, “well, I guess that’s why you’re still in business. You don’t screw up.”

He turns thoughtful, “I try not to make mistake. I don’t know. I think it’s experience. If you have experience, you’re not afraid for this job. Sometimes I am tired, and I say to myself ‘Leave it.’ and after a while, something is coming in my mind to try…”

“You go home and sleep on it,” I observe.

“Yea, yea, and then the next day I say, ‘Oh, it’s okay, I do it like this.’”

“Do you ever ask for help?”

“Yes, if there’s a big problem, I go to the supply store where many shoemakers go, and I ask: ‘What do you do with this?’ because sometimes we can’t find the right glue.”

The right glue? I wonder. Are there more than three?

“Yea, there are different types of glue, ten or twenty different types of glue…”

“We spend more time talking than to do the job,” Yakhil laughs.

An Uzbek man enters, chatting in the mother tongue. He opens a box on Yakhil’s workbench to reveal black ladies’ boots with kitten heels and intricate white side stitching. The master shoemaker turns them over slowly, again and again, like a radiologist reading a mammogram. There are zippers on both sides of the boot, one functional, one faux. The customer is begging. Yakhil is nodding, listening, while his critical eye never leaves the leather. He shakes his head.

“Da, da it’s the design,” he says in English, turning to me. “Boots too tight. This guy says he wanna use this other side to open, to loosen them, but there’s no real zipper there, It’s only the design. Only little bit opens that side, that’s it.”

He puts the lid on the box, gingerly, like closing a coffin, looks the man in the eye, and breaks it to him: “This is too big job. Return them.”

Ahh… the wisdom that comes with experience: know when you’re licked.

I’m wrapping up. Yakhil has been generous with his time. “I’ll be back soon to pick up my own shoes.”

“Do you have here shoes?” he asks.

“Yes, I do, I but I don’t have the money today.” Truth.

I retreat towards the door, embarrassed that my cash flow has slowed to a drip. I’m suddenly sympathetic to all customers whose shoes dangle unclaimed from hooks. And I think about Yakhil patiently safeguarding everything, every pair of resoled boots and mended purse strap, keeping everything until the customer returns, flush from a cashed paycheck.

“What color?” he asks. He may be a hoarder, but Yakhil also knows how to move finished jobs out the door, whenever possible. He’s not letting me go without my shoes.

“They’re gray I have the ticket though…” I’m rifling through my purse; I come up with an accordion sleeve of photos of my sons, and an unclaimed dry cleaner receipt (I also don’t have funds to fetch my slacks this week.)

“Gray heels,” I say.

“No, the ticket color, not the shoes,” he counters.

“Red! I finally come up with the red ticket. “You change the color of your ticket every month?”

“No, When the roll runs out, I switch color.”

“When you switch to a new roll, the unclaimed shoes go downstairs?”

“Yea”

“Oh boy, so what color did you just send downstairs?”

“Any color. It doesn’t matter. It’s mixed.”

I’m skeptical of the system, but it works for Yakhil and he never loses anyone’s shoes. It’s a point of pride.

He hands me my shoes, beautiful work, as usual. Gray heels with a peek-a-boo detail—on the heel—not the toe, a fetishist’s delight.

“I don’t have the money to pay you today…” Tail between my legs.

“No problem. Come back when you can.”

I slip on my beautiful gray heels before I leave, impractical yes, but wearing new (or resoled) shoes, straight out the door, is one of life’s little pleasures… so is having a friendship with your cobbler. As I leave, he chuckles softly, betraying that enviable, easy confidence in himself, that has always made him comfortable tackling any job, big or small.