Working to Make Brooklyn’s Indigenous Communities Count

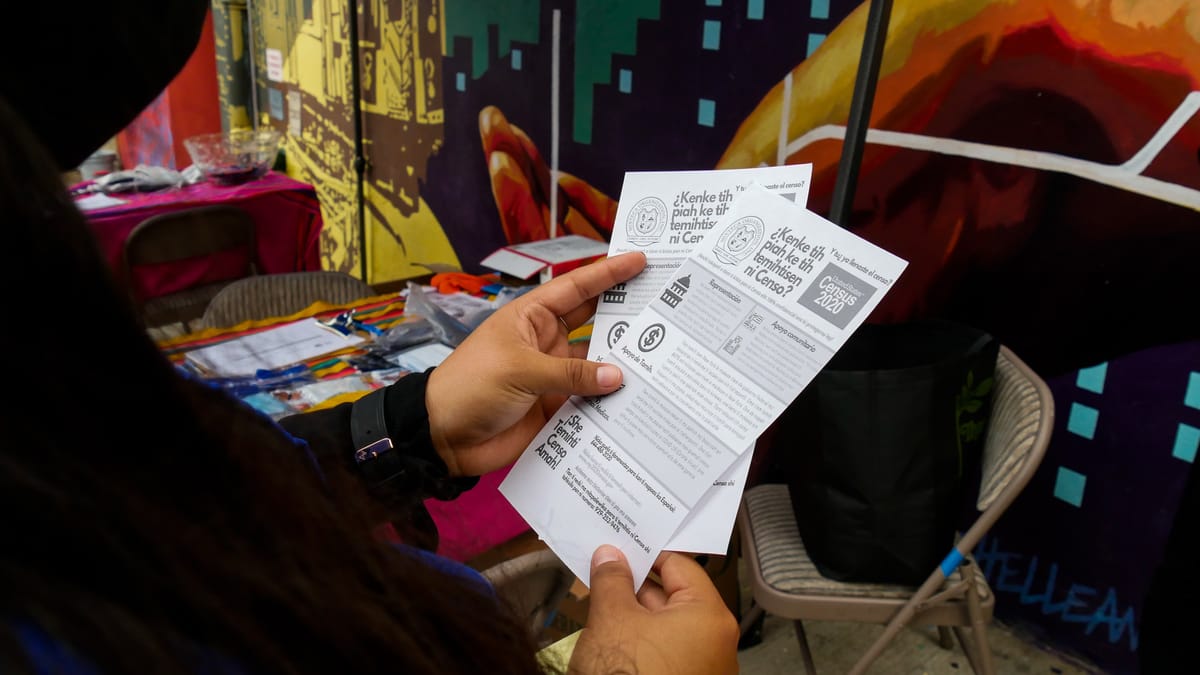

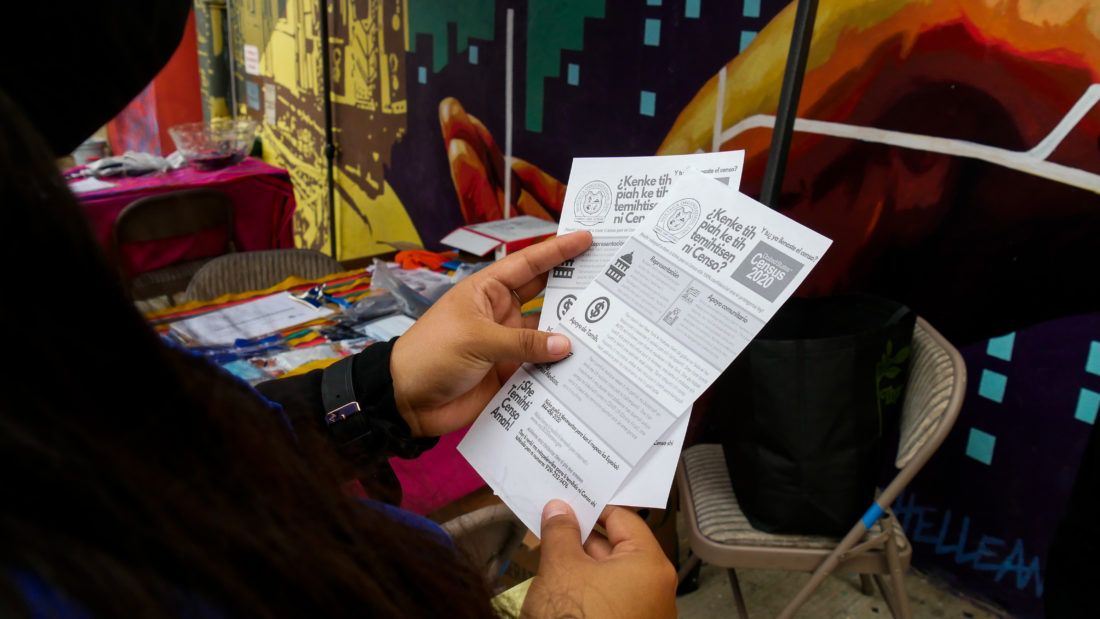

Mixteca Organization, serving Sunset Park’s Central American community, has been doing census and COVID-19 outreach in four different Indigenous Mesoamerican languages in addition to English and Spanish: Tu’u Savi, Ki’iche, Nahuatl, and Mixe, which are all spoken in Sunset Park.

While no one knows exactly how many speakers of Indigenous Mesoamerican languages there are in the neighborhood, Mixteca held events almost every day in September to make up for time lost to do in-person outreach earlier this year due to the pandemic restrictions. At these events, Indigenous speakers were present to engage with the portion of Sunset Park’s Mexican immigrant community that is not comfortable with Spanish.

“The only thing I don’t do in Sunset Park is sleep,” said Lorena Kourousais, the director of Mixteca who is originally from Mexico and has been the Executive Director of Mixteca for almost a year. Kourousais and her team have been working around the clock to make sure Sunset Park has an accurate count.

Sunset Park is located in Brooklyn Community Board 7 in which 46% of residents are foreign born and 40% are Hispanic or Latino, according to data from the New York City Planning Department. Dr. Daniel Kaufman, the founder of the Endangered Language Alliance, said that recently “the major sending zone from Mexico for immigrants to New York expanded from Puebla into Guerrero. Guerrero is really one of the most neglected rural states in Mexico. And the majority, especially from the sending region, are Indigenous and speakers of an Indigenous language.”

In April, many Sunset Park residents were struggling to pay for food and rent. “We realized that the community really needed access to money at that time,” said Kourousais, and Mixteca launched an online application for aid. It was filled out by more than 4,000 people in 59 languages, Kourousais told Bklyner. The Indigenous languages of Tu’u Savi, Ki’iche, Nahuatl, and Mixe were among them, prompting her to find a way to help the Indigenous language speaking part of the Mixteca community.

“I think this is one of the reasons why the census completion rate is still low in Sunset Park, there are many communities that speak Indigenous languages. It is another way for this population to really be left out of everything,” Kourousais said. The current self-response rate is 59% for Sunset Park’s congressional district, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

According to the most recent census data, there are over 15,000 people of Hispanic or Latino descent in New York City that speak a language other than Spanish and English at home. While it does not specifically identify speakers of indigenous languages, and would include speakers of other tongues, this is the only representation of New York City’s Indigenous language speaking Central American immigrant community in census data.

Jeff T. Behler, the New York Regional Director for the U.S. Census Bureau said that the strategy for 2020 census count was to partner with local trusted voices. Behler said that neighborhoods that are “hard to count” are, “typically communities of color where there’s a lot of renters, where there’s a language barrier, and where there’s children under the age of five.”

Dr. Kaufman’s organization, the Endangered Language Alliance, has made census outreach videos in Indigenous Mesoamerican languages. Kaufman said, “people were just excited to hear their language and see people from their community presented that way and working as if they count, because these communities are really invisible, not only here, but they’ve also been made invisible in Mexico.”

Reyna Martinez is a Nahuatl speaker who helps Mixteca with outreach. She told Bklyner, in Spanish, “I’ve been in this country for 17 years. Yes, I have met people who speak my language. But, many have told me that at times they feel ashamed to speak the language.” She said she feels good that she can help Nahuatl speakers fill out the census because “the purpose of the census is to be counted, which helps the children’s schools and programs for adults.”

Staying in the shadows can be a method of survival for undocumented communities. “One of the strategies for these communities is to be invisible. But on the other hand, if we are not providing this information it is like we continue erasing communities that are there,” said Kourousais.

Samantha Ciriaco, the Census Community Organizer for Mixteca, said that she has noticed a lot of participation because the community has built trust in Mixteca. Providing information in Indigenous languages helps to build that trust. She said, “this community has been historically undercounted, I personally spoke to members that didn’t even know what the census was.”

Kourousais worried about not being able to pay the “lenguas originales” team. She said, “we had a challenge because city initiatives or funding from the state wouldn’t allow us to hire anyone without employment authorization.” Mixteca ended up securing funding from Robin Hood, an organization fighting poverty, to hire and train Indigenous language outreach workers to support census outreach.

Ciriaco thinks the census could do more. “I would like to see more community information collected in Indigenous languages,” she said. Ciriaco acknowledged her community’s initial distrust of the census, but thinks “people would be willing to give more information because Mixteca has shown them the census is trustworthy and it is important for the next ten years.”

Behler praised groups like Mixteca for the work they have done. He said, “They truly are amazing. They reengineered themselves, they went virtual, they went via social media, and now they’re doing things at food distribution sites. So they are finding the places where people are gathering and putting the message out there.”

The census deadline has been extended until October 5th.