Why The MTA Is On The Wrong Track

THE COMMUTE: In this three-part series, Allan Rosen discusses, in Part 1, the back-story and success of the 1978 Southwest Brooklyn bus route changes, and why this is how the MTA should do its bus route planning. Last June, Allan explained what is wrong with how the MTA does its short-range planning. In Part 2 of this series, he goes into more detail explaining how their approach is leading us toward disaster. Part 3 shows the future direction the MTA must take to avoid destroying the local bus system, the path it is currently on.

Last week I discussed the Southwest Brooklyn bus route changes made in 1978, which was the correct path toward improving service. This week I discuss the current path the MTA is on, where that path will lead, and the need to regain control of the system.

The MTA’s Misguided Mission

Unlike DCP’s goal, to cultivate ridership by restructuring bus routes to improve connectivity between neighborhoods, the MTA’s mission is to reduce costs by cutting service even if those service cuts result in more inefficient services. They mix improvements with service cutbacks, necessitating the use of three buses to complete a trip where only two buses were required previously, or severing bus connections entirely, forcing former bus riders to rely on car services or make a longer more inconvenient subway trip. When that is the way you plan, there is no wonder why bus ridership keeps going down, but the MTA finds that a mystery.

The MTA’s Current Direction In Bus Route Planning And My Predictions

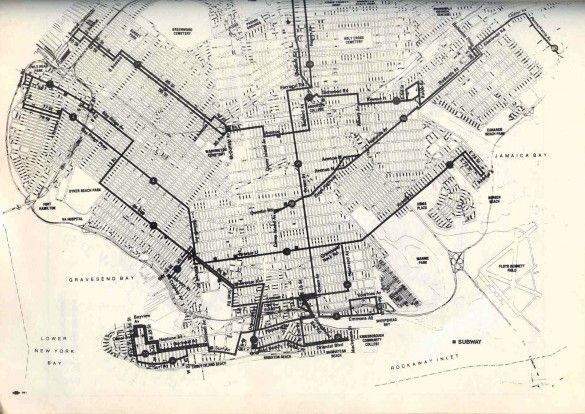

The MTA is attempting to create a few “super routes” with its local bus system [some of them Select Bus Service (SBS) routes] spaced every mile with good headways compared to the current standard of half-mile spacing, eliminating all other routes except for routes necessary to feed the subway. Those routes, because they serve only one purpose — to get people to the subway — are only well-utilized during rush hours and inefficient at other times. Increased spacing between local bus routes and increasing distances between bus stops, which is what they are also doing, will increase walking distances to bus routes more than the quarter-mile walking standard used in the industry, making them less attractive. In some cases, increasing bus stop spacing does make sense, but sometimes it does not.

The MTA is taking these steps to force more passengers away from local buses and onto the subway because it is cheaper for them to operate the trains since they carry more people and use less direct labor. If those subway trips take longer, are more inconvenient, or are more indirect for the passenger, that is not the MTA’s concern.

What the MTA does not realize is that in order for many passengers to use those super bus routes they are creating by destroying parallel routes, moderately- and lightly-used routes must still exist to permit access to those super routes because most people do not live near thoroughfares such as 86th Street, Flatbush Avenue, Nostrand Avenue, Utica Avenue, Church Avenue or Flatlands Avenue, where those super routes operate. Those routes targeted for eventual elimination are the ones they are reducing service on and truncating, for example the B48 and B64, where the process has already begun.

In another example, the B49 along Ocean Avenue used to operate at eight-minute headways. Service has been reduced to 12 minutes, even during rush hours. The B44 SBS, with more frequent service, will divert some B49 riders to the SBS, resulting in the MTA further reducing B49 service to perhaps every 15 minutes. This will have the effect of increasing the actual frequency you have to wait for a bus to 30 or 45 minutes due to bus bunching or buses not stopping due to overcrowding. That will further discourage bus usage, causing more riders to use longer, indirect subway trips to get to where they are going, resulting in additional reductions to bus service. The MTA is not dumb; this is their intention; they want to provide less bus service.

I will go one step further by predicting that, within a few years, they will propose to reroute the B44 SBS northbound local from New York Avenue to Rogers Avenue beside the SBS and seek to terminate the B49 at its northern end at Foster Avenue and Flatbush Avenue, cutting it back from Fulton Street. This will further erode ridership due to fewer connections with other bus routes and cause headways to be reduced to every 20 minutes. By 2020, the MTA will declare the B49 redundant and not necessary because it parallels the Brighton subway, and will seek to eliminate it entirely. The B44 SBS will also siphon some passengers from the B4 due to its superior headways when compared to the B4. That will be enough reason for the MTA to once again propose that the B4 be entirely eliminated east of Coney Island Hospital. Since there will be no public outcry, this time they will succeed.

The B44 SBS will result in a degradation of service on the B44 local, the B49 and permanent elimination of the eastern end of the B4 within the next few years. It will only be a significant improvement for a few, attracting riders from other bus routes, which will suffer, and not cause anyone to leave their car at home to take the bus instead. Parking availability or lack thereof at someone’s destination is the major reason one decides whether to leave his car at home or not; a savings of four minutes to the average SBS passenger will not alter that decision.

If you find these predictions difficult to believe, just look at the history of the B2. The MTA took a route that used to have one of the best service levels in the borough during rush hours — a bus every two minutes — and steadily reduced service until it barely operates at all despite the opening of Kings Plaza in 1971 at its eastern end. Overnight service was eliminated a few years ago and weekend service was eliminated just last year. The route is one step away from total elimination.

The MTA had numerous opportunities to make the B2 successful again by turning it from a subway feeder, primarily used during rush hours, to a multipurpose route by extending it westward, filling a service gap along Avenue P and extending it into Bensonhurst or Bay Ridge. They chose not to.

Monthly passes will become increasingly more expensive and more people will be forced into buying them as increasing numbers of trips require three buses and a double fare. The MTA would like that. This is what happens when your only concern is reducing costs, and you do not care about your customers.

Regaining Control Of The System

A sensible route restructuring plan for the B49 with the implementation of the B44 SBS would be to reroute it straight along Ocean Avenue to Empire Boulevard, a thoroughfare lined almost exclusively with six-story apartment buildings, making it more direct, and removing some of the mystery to new users of the system. However, the MTA believes that no one chooses to use the bus system but does so only because they have no other choice. They also believe that Ocean Avenue is too close to Flatbush Avenue for a route to be viable there because Flatbush Avenue already has a bus route of its own. The fact that the Flatbush Avenue route veers away in an opposite direction toward Kings Plaza and Bergen Beach, whereas the B49 goes toward Sheepshead Bay and Manhattan Beach, is not a consideration by the MTA. Nor do they consider that where the B49 currently operates — on Bedford Avenue and Rogers Avenue — is also one block away from two other bus routes and the residential densities there are lower than on Ocean Avenue.

No one questions why there are four routes in Manhattan all operating along the same portion of Fifth Avenue, so what would be wrong with straightening the B49 and making it more direct to ease transferring? Currently, someone traveling north along Ocean Avenue wanting to go to Kensington, for example, must first veer out of their way to Rogers Avenue, adding a needless 15 minutes to their trip. Needlessly complex routing discourages bus usage.

The MTA must not be allowed to continue down its current path — one of destroying many local bus routes. We must regain control of the system by insisting they fill long-standing service gaps like the ones along 13th Avenue and Fort Hamilton Parkway in Borough Park, and in East Flatbush, where bus travel has been difficult for 70 years. They must not be allowed to create new service gaps like they did when they cut back the B4 and eliminated the B71 on Union Street in Park Slope, a route that saw ridership increase 29 percent in the past five years, a fact the MTA chose to ignore when making its decision to eliminate that route.

MTA’s Planning Assumptions

When you plan under the following assumptions: 1) That you lose money with every bus passenger you carry; 2) No one uses your service unless they absolutely have to because they have no other choices; 3) When you cut service all passengers will use an alternate mass transit route and you will not lose any revenue; 4) When you add service you will not attract new passengers; 5) When you do lose passengers to other alternatives like car services, they no longer need to be considered as part of demand; and 6) You make no attempt to attract new passengers who are not currently using the mass transit system; you are dooming yourself to failure. This is the course we are on.

You assume the only way to cut your deficit is by reducing service and therefore you erode service, causing further patronage losses. Your reduction of service is accomplishing your goal of reducing your deficit by driving passengers away to other modes of transportation or causing them not to make trips they otherwise would have made. You do not care if your service reductions make the system more inefficient by increasing the cost per passenger to provide service. You only care that you are spending less money to provide service.

Next Week, in the final part: My experiences in Operations Planning and the Correct Path for the MTA.

The Commute is a weekly feature highlighting news and information about the city’s mass transit system and transportation infrastructure. It is written by Allan Rosen, a Manhattan Beach resident and former Director of MTA/NYC Transit Bus Planning (1981).