Top NYPD Brass Clears the Air About New Marijuana Enforcement Rules in Communities of Color

BROWNSVILLE — Residents in over-policed communities of color have historically been disproportionately jailed for smoking pot. Now that state lawmakers have decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana, politicians and law enforcement want people in those neighborhoods to understand the new rules.

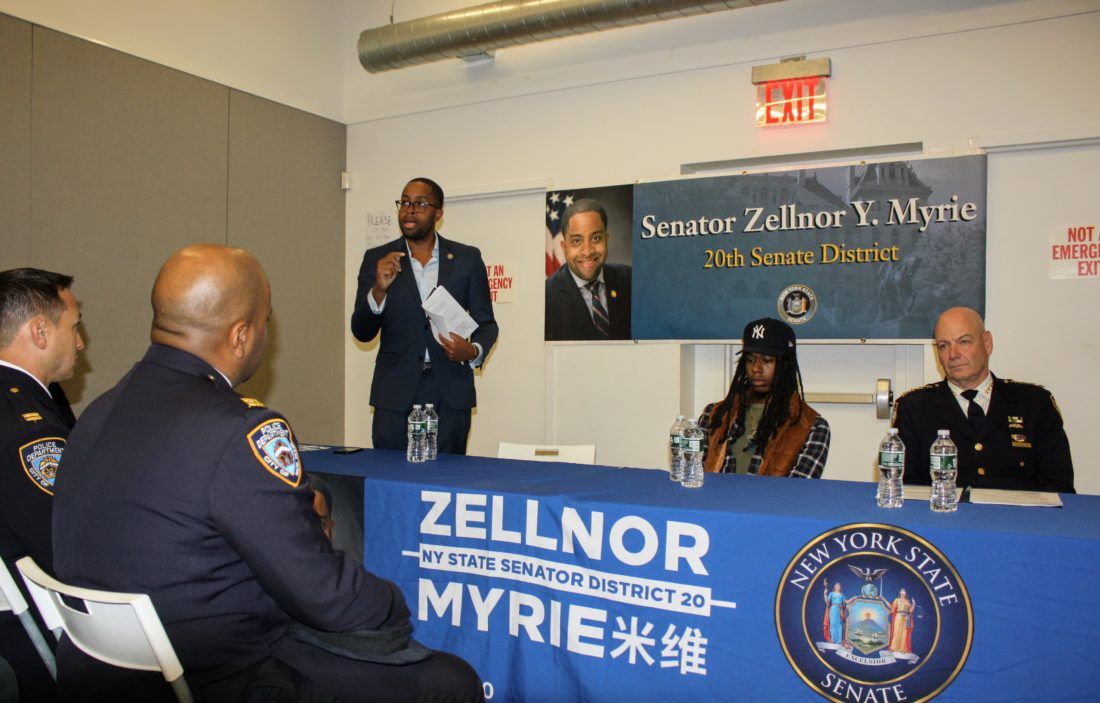

New York State Sen. Zellnor Myrie (D – District 20) held a town hall meeting on Tuesday night (Oct. 8) in the Brownsville part of his district. He moderated a conversation between NYPD high-ranking officers and residence about marijuana decriminalization.

Under state legislation passed in July, the penalty for unlawful possession of small amounts of marijuana has been reduced to a violation punishable by a fine—not incarceration. The new law also expunged some past convictions.

“It’s very important that we hear how they (NYPD officials) view enforcement and how they view the policing of the law because that will inform how the community interacts with law enforcement,” said Myrie, who co-hosted the event with fellow Brownsville lawmakers Assemblywoman Latrice Walker (D – District 55) and City Councilmember Alicka Ampry-Samuel (D – District 41).

NYPD Chief of Department Terence Monahan delivered an unambiguous message.

“I want to be clear on one thing: Marijuana is not legal. It was decriminalized. It is not legal to possess marijuana. It went from a crime to be arrested for to an offense that you could get a fine for,” he stated.

Monahan added that one of the most common complaints the police receive is about someone smoking marijuana in public places.

“I want to be clear on one thing: Marijuana is not legal. It was decriminalized. It is not legal to possess marijuana. It went from a crime to be arrested for to an offense that you could get a fine for,” he stated.

“When a cop catches you smoking a joint in the street, he has discretion about what he’s going to do. He could give you a summons to appear in court. If you ignore that summons, you could get a warrant,” the police chief explained.

This comes against the backdrop of a long history of disproportionate enforcement of marijuana laws despite relatively equal use among races and ethnicities. Will that history could continue under the new rules?

A reduction of prosecutions in Brooklyn for marijuana possession preceded the new law. There was also a reduction in arrests, but Black and Hispanic Brooklynites were still arrest at significantly higher rates than Whites. In the first three months of 2019, Blacks accounted for 62 percent of arrests for smoking weed in public compared to just 4.2 percent of Whites, according to NYPD.

“To put it diplomatically, we’ve had friction as a community with the police,” Myrie said, emphasizing to attendees that the forum was “not an opportunity for folks to bash law enforcement.”

Monahan acknowledged that many residents in communities of color resented what they viewed as an unnecessarily heavy-handed approach to law enforcement in their neighborhoods. Since 2014, the NYPD has adopted a less confrontational neighborhood policing approach, he said.

“We don’t need to blanket a community and arrest everyone. We know that there’s a small percentage of people who will do the violence,” the police chief stated. “The whole concept of neighborhood policing is to give cops discretion. Not every incident leads to an arrest, not every incident leads to a stop.”

Under this new way of doing things, police officers theoretically get to know residents in the community they serve. That will enable cops to distinguish a gang member from a youth who made a bad choice to smoke a joint in a playground.

Kwesi Johnson, an activist who works with several community-based organizations in Brownsville, said at the forum that he’s noticed a lot of positive changes in how cops police Brownsville, one of Brooklyn’s most violent neighborhoods.

However, he urged the commanders to train their officers to be “more thoughtful” of how they treat community members during policing encounters.

“There’s still a lack of communication,” said Johnson, who has lived in Brownsville for 20 years. “I’ve woken up to see a big police RV in the neighborhood. When that happens, people are scared. Sometimes it feels like you’re being watched.”

Monahan assured Brownsville residents that RVs are parked in the neighborhood usually because “something bad happened,” like a gang shooting. He encouraged them to just ask the officers questions.

“Come in and speak, human-to-human, with that cop,” he urged.