Thirty-Third Anniversary Of The Southwest Brooklyn Bus Route Changes

THE COMMUTE: In this three-part series, Allan Rosen discusses, in Part 1, the back-story and success of the 1978 Southwest Brooklyn bus route changes, and why this is how the MTA should do its bus route planning. Last June, Allan explained what is wrong with how the MTA does its short-range planning. In Part 2 of this series, he goes into more detail explaining how their approach is leading us toward disaster. Part 3 shows the future direction the MTA must take to avoid destroying the local bus system, the path it is currently on.

The date November 12, 1978 probably means nothing to you unless it was the day you were born or got married. For me it was a very special day. It was when the MTA implemented the southwest Brooklyn bus route changes I had been working on for four years at the Department of City Planning (DCP). It was the day that the B21 was replaced by an extension of the B34 and the B1 was rerouted to Brighton Beach Avenue from the Sheepshead Bay Station it previously served. It was the day the B49 was rerouted to the Sheepshead Bay Station to replace the loss of the B1. It was the day the B4 was extended from Bay Ridge (not my idea) to replace the B21 on Emmons Avenue and the day the B36 was moved from Neptune Avenue to Avenue Z to provide a through route along Avenue Z also replacing the B21. If you are having a difficult time following this, that is because it was the largest and most complex routing changes ever made in Brooklyn or the entire city on a single day until last year’s service cutbacks. Except in 1978, routing improvements were the focus, not service reductions.

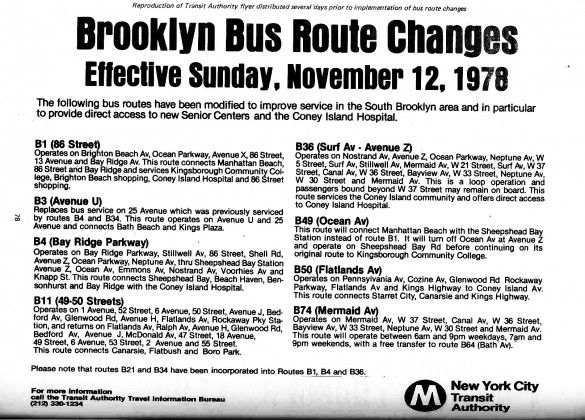

The MTA also chose that day to initiate service on the B50 along Flatlands Avenue, a route it had received a franchise for three years earlier but chose not to operate until 1978. It was later combined with the B5 to form the current B82. Altogether there were major changes to 10 local Brooklyn bus routes that Sunday, resulting in massive confusion around Sheepshead Bay Station due to inadequate public notice and an impossible-to-read black and white map on the reverse side of the flyer shown above, distributed only three days prior to the changes. Every route passing the station was new and now stopped at a different bus stop or went to a new destination. Last Saturday marked the 33rd anniversary of those route changes.

Getting them accomplished was no easy task. It was the only time in history that another agency successfully instructed the MTA how to alter its bus routes. It required two years of the MTA stalling and two years of negotiations as well as a lawsuit to make those changes a reality.

Why Those Changes Were So Important

The changes proved that comprehensive bus routing studies really do work. The MTA has long insisted that they do not work and vowed around 1995 never to do them in the future, and they have kept that promise. Comprehensive studies just haven’t worked when the MTA conducted them, because they refused to negotiate with the communities when some of their suggestions met opposition.

Subsequent to the DCP Study, the MTA conducted comprehensive studies in Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island and in Manhattan in the early 1980s because they never wanted another agency to do their planning for them ever again. (Their Bronx Study was conducted at the same time as the DCP study.) All those studies resulted in changes to only two bus routes in Staten Island. Two more comprehensive studies conducted by the MTA in the Northeast Bronx and Southern Brooklyn around 1993 also failed, resulting in no changes at all.

The MTA presents their plans on a take it or leave it basis, or else disregards community opinions altogether and just goes ahead with its plans anyway. Their refusal to negotiate with Co-Op City buried their Northeast Bronx study, and the results of their 1993 Southern Brooklyn Study were withdrawn when the MTA claimed there was no money to make their proposed changes. Between $3 and $6 million were wasted by the MTA undertaking these studies. The successful Southwest Brooklyn Study conducted by DCP cost only $250,000.

Around 2001 when the MTA proposed to extend the B13 to the Gateway Mall in Spring Creek (a good idea), they combined it with eliminating the B18 (a poor idea). They also combined the B40 and B78 to form the B47 (another good idea, one which I also proposed in my 1972 Masters Thesis), but they also insisted on eliminating the east-west portion of the B40, making bus connections between Crown Heights and Ocean Hill more difficult (a poor idea). At the public hearing for all those changes, not one person spoke in favor of any of them, but the MTA proceeded anyway without any making any alterations. In Planning, the idea is to minimize any inconvenience while doing the maximum amount of good. When the MTA plans, they just mix good and poor ideas, so that some are helped and others are needlessly hurt.

By contrast, the DCP didn’t have to make any modifications to its plan. Three of the community boards approved all the proposed changes outright while the three boards that were minimally affected took a neutral position. That proves if you make sensible proposals that do not needlessly hurt communities and are honest with them by telling them the entire story — the advantages as well as the disadvantages of your plan, as DCP did — they can come to an informed decision and they will support your plan. After a large section of the B1 was eliminated along Avenue X east of Ocean Parkway as part of the 1978 changes, the MTA received only one written complaint.

Compare DCP’s honest approach to how the MTA approached the communities with their B44 Select Bus Service Proposal, providing conflicting and partial information as well as failing to respond to questions such as the number of parking spaces to be eliminated. That was why CB15 had to request a second presentation. In fact, the only opposition the 1978 changes received was as a result of two of the three modifications the MTA insisted on making, which ultimately failed. Rather than extend the B11 from 18th Avenue to Coney Island Avenue as a trial as DCP proposed, the MTA insisted on extending it all the way to Canarsie. The alternative given to the community was to leave the route unchanged. Reluctantly, CB14 agreed to the MTA’s proposal. The length of the new route proved unworkable and, a few years later, it had to be cutback to Brooklyn College where Community Board 14 originally requested it terminate as a compromise.

The MTA also insisted on the B36 using Surf Avenue in only one direction. That decision was reversed in six weeks after Coney Island residents took to the streets to demonstrate by the hundreds against the change. Full two-way service on Surf Avenue was eventually restored. Because of the MTA’s alterations to DCP’s plan, the agency refused to support the plan it initiated and took a neutral position on the final MTA proposal.

What The Southwest Brooklyn Changes Accomplished

The theory behind the plan was to fill service gaps, make bus routing simpler and more direct where possible, and to encourage bus usage by enabling more trips to be completed using one or two buses — and it worked. The lightly-utilized B1 and B21, which operated every 20 and 15 minutes, respectively, were restructured, and the resulting B1 now operates at eight-minute intervals and in some portions of the route as frequent as every three minutes. It made a one-bus trip possible from Sheepshead Bay and Brighton Beach to Bay Ridge and Bensonhurst. Before 1978, those trips required two, three or even four buses. It extended the B11 from 18th Avenue to Midwood, vastly improving connections there, providing direct bus service where formerly three buses were required. Bus frequencies increased as well, while service on many other routes in the borough were being reduced.

It increased the number of routes serving Coney Island Hospital from one route stopping at its door, (B21 only serving Brighton Beach and Sheepshead Bay) and another a quarter-mile away, the B68 serving Central Brooklyn, to three routes stopping at its front door serving a good portion of Brooklyn and leaving the B68 unchanged.

Other proposed changes, initially rejected, were implemented years later such as the extension of the B82 from Canal Avenue to Coney Island and the extension of the B68 from West Fifth Street to Coney Island.

What The Southwest Brooklyn Changes Did Not Accomplish

As complex and successful as it was, the MTA only chose to implement 25 percent of DCP’s plan. It also included rerouting the B1 along 86th Street to Bay Ridge, a long overdue change finally accomplished last year and first proposed by the Bay Ridge community in the 1960s, unbeknownst to me when I recommended it in 1975. (The DCP plan however, would have served the entire 86th Street from end to end and the route would have been numbered B86 for it to be easy to identify.) However, I would have accomplished that change not by flip-flopping the B1 with the B64 as the MTA did, an alternative I ruled out after reviewing the results of our origin/destination (O/D) study that showed too many people would be inconvenienced. The MTA never performed any O/D study and relied solely on passenger counts, a method that is supposed to be used only to plan schedules, not bus routes.

The DCP proposal recommended the meandering B16 serving Fort Hamilton Parkway and 13th Avenue be split into two direct routes along each of those streets in order to make bus transferring more direct and to better serve Maimonides Medical Center. This important traffic generator has only one east-west bus route serving it and an elevated line over a quarter-mile away. The DCP proposal would have added a north-south bus route greatly improving access to the hospital, like we did with Coney Island Hospital. You can see all my proposals for southern Brooklyn including the DCP proposals here (Note that the site has not been updated in four years.)

Every single proposal described there was presented to the MTA and rejected except for the B83 extension to the Spring Creek Gateway Mall, a simple change that they finally adopted after five years of study and initially rejecting it. Where the MTA gave reasons for their rejection of my proposals, their logic was flawed, contradictory, or they responded to a different proposal than the one I suggested. Not one of the proposals was objectively analyzed because of their arrogant attitude that no one tells the MTA how to plan.

The B16 connecting the lower half of Fort Hamilton Parkway with the upper half of 13th Avenue once made sense when it was created in the early 1930s. Back then, Maimonides was just a small hospital known as Israel Zion Hospital and the lower half of 13th Avenue was mostly undeveloped with no street connection over the Sea Beach tracks and Long Island Railroad. A through 13th Avenue bus route was not possible and a through Fort Hamilton Parkway route was not necessary. A bridge over the tracks was built a few years later, and the hospital became a major borough institution in the following decades, but the bus routes were never modified to reflect those changes.

Even when there is a major land use change today, the MTA makes the minimum bus route alterations possible and only after elected officials prod them to take action. The Aqueduct Racino opened last month and the MTA’s response was only to reroute one local bus a quarter-mile without considering the impact to the current riders, adding 10 minutes to their trip rather than making substantial route changes to adequately serve a change of that magnitude.

Next Week: Why the MTA is on the Wrong Track

The Commute is a weekly feature highlighting news and information about the city’s mass transit system and transportation infrastructure. It is written by Allan Rosen, a Manhattan Beach resident and former Director of MTA/NYC Transit Bus Planning (1981).