The History Of Manhattan Beach And Brighton Beach

In the 1870s, Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach were some of the poshest digs this side of fancy-town; an exclusive getaway for New York’s monocle wearing upper-crust. A fascinating report by Curbed traces this history, a time when the two beach communities were once dotted with lavish hotels and resorts.

Right off the bat, we learn that Manhattan Beach had a “creator” in the person of wealthy railroad tycoon (and notorious anti-Semite) Austin Corbin. Corbin began investing heavily in the area when a doctor told him that seaside living would improve his son’s health. Curbed describes the birth and subsequent expansion of the early Manhattan Beach community:

Corbin was a guest at the Ocean Hotel owned by William Engelman, a man who made his fortune selling horses to the government during the Civil War. While there, Corbin set his sights on the uninhabited swampland east of Engelman’s property, realizing its potential as a resort destination. He chose the name “Manhattan Beach” in the hope that its cosmopolitan flavor would attract a clientele of the same ilk. Also recognizing that the remote location required transportation access, he used his power as president of the Long Island Railroad to construct the New York and Manhattan Beach Railway, bringing the shore within one hour of uptown New York.

After Corbin got the trains connected to the city, the luxurious Queen Anne-style Manhattan Beach Hotel opened for business on July 4, 1877. Attracting former President Ulysses S. Grant to the grand opening ceremonies, the hotel held the reputation as “the best hotel on the Atlantic Ocean” according to an ancient review in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Curbed described some of the amenities available at the four-story wooden hotel as well as Corbin’s continued expansion of the area:

[T]he hotel featured 150 guest rooms as well as an assortment of restaurants, ballrooms, and shops and offered first class entertainment—John Philip Sousa performed here and wrote the musical piece “The Manhattan Beach March” in the hotel’s honor in 1893. In addition, exclusive New York clubs such as the University Club, the Union League, the New York Club and the Coney Island Jockey Club used the resort as their summer headquarters. Based on the success of his first hotel, Corbin would build another three years later—the Oriental Hotel. An opulent hotel with a Moorish motif, this hotel catered to the wealthiest of families, offering them suites for extended stays throughout the entire resort season.

Engelman, the hotel proprietor who originally hosted Corbin in his own Ocean Hotel, was not to be outdone. He created his own resort, which he dubbed Brighton Beach, inspired by the British seaside location. Engelman built the Hotel Brighton in 1878 right by the shore but in 10 years time, Mother Nature had intervened forcing dramatic action to save the hotel:

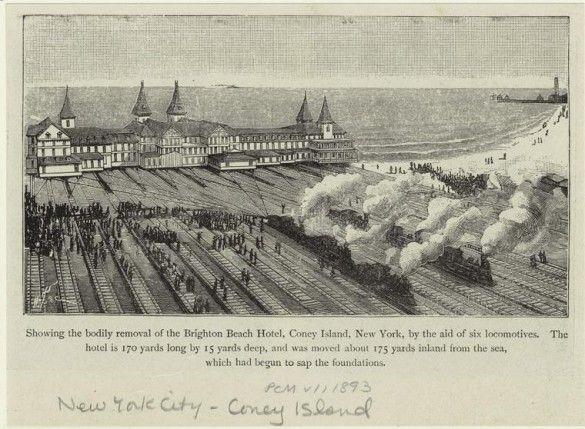

The beach in front of the hotel would become so badly eroded that the ocean waves would lap up against the hotel’s façade. To save it from destruction, the hotel was placed atop 120 railcars and moved inland 500 to 600 feet [pictured above]. This massive job only took three months to complete, meaning the hotel was open for business again in the summer of 1888. Engelman failed to lure Corbin’s wealthier clientele, however, because they did not wish to be any closer to Coney Island.

The resort business was booming in the late 19th century as wealthy patrons enjoyed horse-racing particularly. The area soon became the top horse-racing spot in all of America. Despite the success of all the hotels and resorts, their popularity quickly waned due to a ban on gambling which killed the horse-race loving crowds. Curbed describes the gambling prohibition and other factors which led to the end of the resorts by the 1920s.

The amusement parks opening in West Brighton, the suburbanization of parts of Brooklyn, and the Manhattan Beach Improvement Company selling off parcels of land for residential development. But what truly destroyed these areas was the prohibition of gambling, forcing the once very lucrative horse tracks to close, thus causing many patrons to stop coming to these resorts. Between 1910 and 1920, both the Manhattan Beach (1911-2) and Oriental Hotels (1916) were torn down and the land was sold for residential development. Although once considered a negative, the Brighton Beach Hotel’s close proximity to Coney Island, which was at its peak during this time, meant that the Brighton Beach Hotel fared a bit better—it stood until 1926. Although these hotels were gone, the area remained popular for its Manhattan Beach Baths, a bungalow and bathhouse community with daily concerts and dance. The baths closed in 1942, marking the end of Manhattan and Brighton beaches as resort destinations.

While Brighton Beach has transformed into a Russian immigrant stronghold and the resorts of Manhattan Beach have given way to private homes, the last remaining artifact of that bygone Victorian era is the boardwalk and the view of the ocean. Am I the only one who wishes they had a time machine to visit the 1880s and see what these areas actually were like in fancier times?