State budget cuts threaten 9,000 teacher jobs and NYC’s in-person learning plans, Carranza warns

By Reema Amin, Chalkbeat New York

Carranza’s comments came during an hourslong public meeting, during which dozens of New Yorkers pleaded with the city’s education department to delay its plans to reopen school buildings on Sept. 10.

If the state follows through on threatened cuts to schools, New York City will be forced to lay off 9,000 teachers, and students will have to learn from home for the year, schools Chancellor Richard Carranza said Wednesday night.

Carranza’s comments came during a nearly 10-hour public meeting that bled into Thursday morning, during which roughly 200 New Yorkers pleaded with the city’s education department to delay its plans to reopen school buildings on Sept. 10. In recent weeks, city educators, citing health and safety concerns, have intensified calls to put off reopening campuses.

For months Gov. Andrew Cuomo has warned that New York State’s fiscal crisis could mean cutting up to to 20% of state funding for various local services, including for school districts, if federal officials did not offer up more coronavirus relief for states. School officials in the city and elsewhere said they learned last week that the state would temporarily withhold payments to districts. (A Cuomo administration spokesperson said the state has withheld these payments since June). Cuomo can move to make these cuts permanent, provided he notifies the legislature, which has 10 days to come up with an alternate plan for saving money. If the funding isn’t restored, the whole school year could be fully remote because officials won’t have enough resources to operate buildings, Carranza said. A shrunken budget could also cost 9,000 city teachers their jobs, he said.

“This is not smoke and mirrors; this is, if we get a 20% cut, we will not be able to open up our schools for in-person learning,” Carranza said at the Panel for Educational Policy, an appointed board that approves major education policies and contracts. “That means that parents who have no other choice will not be able to go out and get a job. It means we will not be able to man our school system.” (Many families have argued that the current hybrid schedules also do not allow parents to work full-time.)

One way to avoid that outcome, he said, would be to borrow money, but that would require approval from the state legislature, which lawmakers have previously rejected.

After days of dismissing calls for a delayed reopening, Carranza signaled support for such a plan Wednesday night, saying that spending more time to plan and communicate with teachers “sounds like really good practice.” But, he said the state could withhold money from the city for not holding the mandated 180 days of instruction. Districts can request a waiver for meeting this requirement. Carranza said he’s talking to the state education department but did not say whether his office has applied for a waiver or what exactly he’s seeking. He has not yet received “in writing, an assurance” that the district won’t be financially penalized for a delay, he said.

Without such an assurance, delaying reopening would mean making up for lost instructional days by canceling breaks, which Carranza said he’s unwilling to do since educators lost their Spring break and the summer while planning for reopening.

Students, teachers, lawmakers, and parents testified over several hours during Wednesday’s meeting, often expressing deep criticism and distrust in the city’s ability to protect students and staff from contracting the coronavirus. Speakers floated several alternate plans, but one after another said the city’s plans to roll out hybrid learning could not happen in the next three weeks without major compromises.

“I feel like a prop to reopen the economy,” said Meril Mousoom, a rising senior at Stuyvesant High School, who was one of nine students of varying ages who spoke at the meeting. All opposed a return to school buildings but called for varying alternatives. A 7-year-old said it would be too difficult for her peers “to stay silent all the way during lunch,” when students will have to remove masks to eat in their classrooms. A rising sixth-grader advocated pivoting to outdoor learning, “especially for younger kids who felt really cut off during this remote learning.”

Speakers raised myriad concerns about the city’s reopening plan. They worried about the risks of virus transmission in school buildings, how the city’s fiscal crisis would impact its ability to buy health and safety supplies for schools, who exactly will teach students learning remotely, and how teachers could be properly trained in trauma-informed instruction before buildings opened.

Naomi Peña, a member of the parent council in Manhattan’s District 1, on the Lower East Side, said parents she spoke with want school buildings to remain closed, but favored learning outdoors, where virus transmission is less likely. They also want to expand city child care centers from the spring, with priority given to students with disabilities, those who are homeless, learning English or are the children of essential workers, she said. (The city has said it will provide child care for 100,000 students this fall, but no other details have been revealed.)

Many speakers said they were part of a parent group called PRESS NYC, which had recently described their concerns in an op-ed for the Washington Post. The group had asked families and elected officials to speak Wednesday in support of a delay. Many teachers who spoke were with MORE, a caucus within the teachers union that has forcefully scrutinized reopening plans.

Families can opt for full-time remote learning at any point during the school year. About 30% of students have so far chosen a fully remote schedule. That number grew by nearly 41,000 students between Aug. 7 and last Friday, and will likely continue to rise ahead of the September start date.

“I sympathize with students and parents who are like, ‘I need to get my kid back in the building because the level of learning is not the same.’ But I have to say, we hear over and over again from our parents that it’s not safe and the plan doesn’t make sense — instructionally, pedagogically, it doesn’t make any sense because these kids aren’t replicating the actual classroom environment they had before,” said Eric Crump, a member of the parent council in District 4, which includes East Harlem.

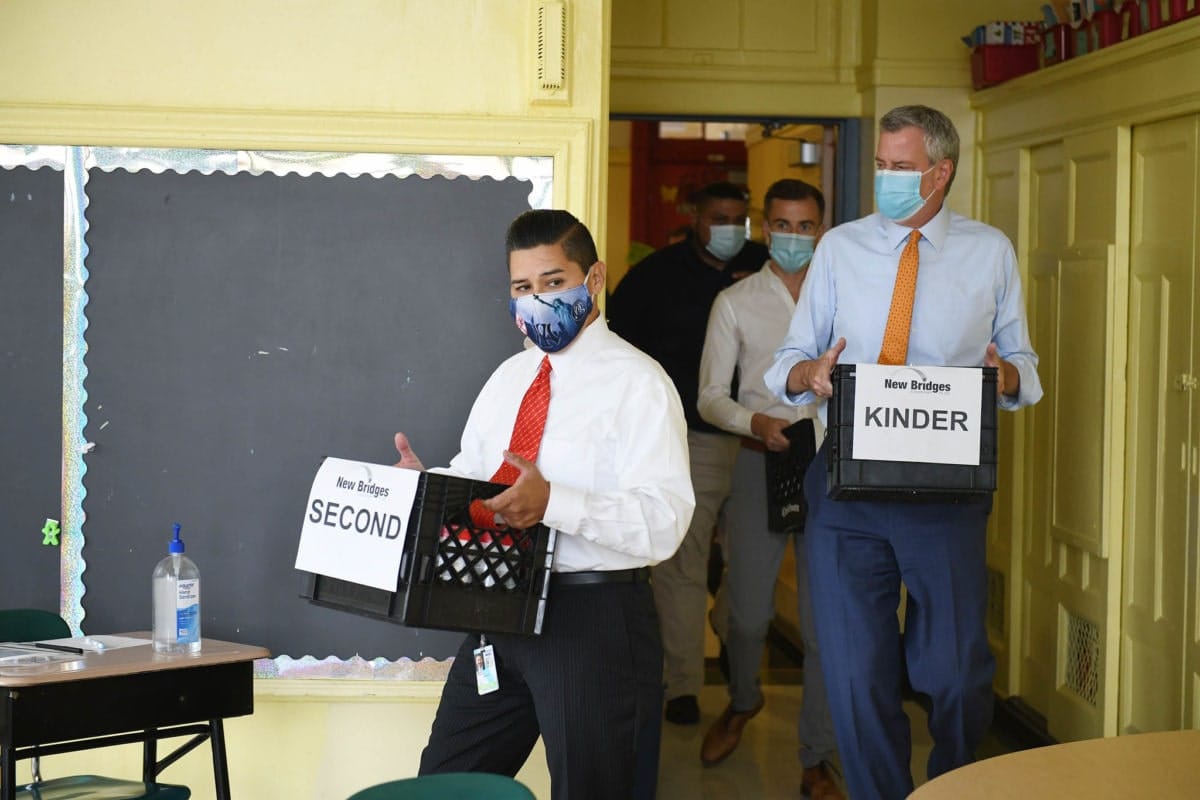

Pressure to delay reopening has intensified in recent weeks from the unions representing teachers and principals, but also from rank-and-file educators who have banded together to publicly share their concerns. Mayor Bill de Blasio and Carranza have dismissed their calls to delay a reopening, instead announcing safety measures, such as equipping every school building with a full-time nurse and creating a hotline for principals who need additional masks and cleaning supplies. During Wednesday’s meeting Carranza emphasized the city’s 0.24% coronavirus positivity rate announced Wednesday morning, a record low since March.

“We are the only school system of the 10 largest in America that is in this position, because of the science, to be able to plan for in-person learning,” Carranza said. “Don’t fall for the urban myth, don’t fall for science fiction. Look at the science.”

Several public health experts have said it’s safe to reopen school buildings in New York City if various safety measures are in place. Education department officials say they have been working for months to repair hundreds of faulty ventilation systems and have put in place robust sanitizing, mask-wearing, and social-distancing protocols.

But some speakers, wary of the massive virus death toll in New York City, questioned the safety of congregating at all — echoing the recent concerns of a longtime health advisor of de Blasio. As the meeting neared a close around 3:40 a.m., three of the 11 panel members also called for a delay.

“We have an overwhelming desire to return to school, but I stress again, one case of positive [coronavirus] — whether it’s from one staff member, a child — is too much,” said Paullette Healey, a parent and member of the Citywide Council on Special Education.

Separately, several people became alarmed after Carranza raised his voice and cut off a parent who leveled allegations of racism against the principal of her Brooklyn elementary school. That parent’s comments came after multiple others raised similar concerns, all naming the principal.

Carranza said he wouldn’t allow the principal to be accused of something in a public forum, where she could not defend herself, and told the parent to contact administrators before asking the facilitator to “take control of the meeting,” who muted the parent’s microphone. Several speakers, including that parent, said they had already unsuccessfully contacted administrators. They criticized the chancellor’s reaction and tone. Carranza defended his comments multiple times during the meeting and forcefully shot down insinuations that he did not care about communities of color.

“I will fight for our children of color, which I’ve done since I got here, but I will also protect the due process of our employees, so do with that what you may,” Carranza said, who later said one of his deputies would look into their complaints.

Panel member Tom Sheppard said he felt that parents were disrespected.

“Mr. Chancellor, with all due respect, I understand what you are saying about slandering someone, but I’m sitting here feeling like a degree of trauma has been inflicted on me and on parents of 1.1 million children,” Sheppard said.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.