Side Hustle To Big Business: Low-Income Entrepreneurs Could Help Brooklyn’s Economy Recover—How Can the City Support Them?

Entrepreneurship and self-employment could be the key to economic recovery in Brooklyn’s low-income communities, but supporting the effort is no simple task.

Despite some strong recent gains, Brooklyn’s unemployment rate sits at a staggering 11.3%, one of the highest rates in the state, and more than three times what it was before the pandemic. The city lost a record 631,000 jobs last year. And though many of the disproportionately low-wage and service sector industry jobs that disappeared will eventually return, most experts say the process could take years.

What’s more, new research from the think tank Center for an Urban Future (CUF) finds that many of the New Yorkers hit hardest by job loss are also those most vulnerable to automation, a trend accelerated by the pandemic that could displace even more workers in coming years.

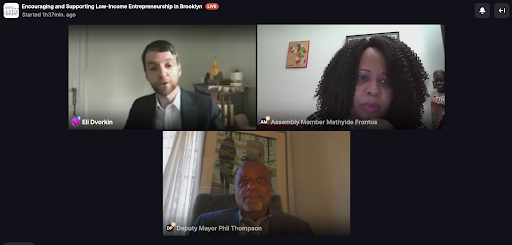

It was in that context that CUF convened a series of conversations to explore how entrepreneurship and self-employment could offer an alternative pathway to economic recovery in low-income communities. A recent panel focused on “Encouraging and Supporting Low-Income Entrepreneurship in Brooklyn” featured Deputy Mayor Phil Thompson, State Assembly Member Mathylde Frontus, and a collection of local economic development leaders and small business owners.

While all the panelists at the Brooklyn event agreed that the city and state can do more to help low-income New Yorkers start and grow businesses, their opinions about how best to make that happen varied.

Thompson, for example, seemed less interested in launching new businesses than figuring out how to scale up existing ones.

“If the community has little money to begin with, then serving each other coffee is not going to get us very far in terms of entrepreneurship,” Thompson said. “We need businesses that connect to other parts of the economy that have money.”

He said there were already 10,000 Minority or Women-Owned Business Enterprises registered with the city, and cited several industries where, he said, “there already are businesses of color in Brooklyn” that could scale if given access to larger private and public sector contracts. Among them: long-term health care and telemedicine, electric car manufacturing, green building retrofits, broadband and housing infrastructure.

Those industries could receive significant money through President Joe Biden’s recent pandemic rescue package and proposed infrastructure spending plan, and Brooklyn could be poised to take advantage.

“Many black and brown people are very familiar with entrepreneurship,” Thompson said. “It’s in the veins. That’s how people survived. We know how to do that. The problem is growth. If we want to grow businesses that have the capacity to really change people’s lives at scale, it’s going to have to be in the sectors where we are not getting the big contracts right now.”

But Frontus—who represents a swath of southern Brooklyn and who unveiled a 6-Point Economic Mobility Plan earlier this year which offers “entrepreneurship training, workshops and individual consultations” for those seeking to start a business—said the government still needs to play a role in getting businesses off the ground.

“When you’re talking about people who need to get started, now you’re talking about my side of town,” she said. “That’s what we’re looking at here in southern Brooklyn.”

She said the government should increase funding to nonprofits that offer aspiring entrepreneurs grants and offer “a whole pipeline” of services, “starting with the starting costs, being able to do the mentorship, being able to help with the fees, which we’d like to get rid of to be very honest, and being able to serve as an incubator.”

“We need to get people off the ground, and that’s the first step.”

The need for the city to fund more one-on-one technical assistance was also emphasized by several of the business leaders who spoke, among them Camille Newman of the Brooklyn Women’s Business Center.

“It’s not only seed capital” that low-income entrepreneurs struggle to access, Newman said. “Hand-holding is not a bad thing,” because low-income entrepreneurs may be trying to teach themselves the mechanics of running a business while juggling multiple jobs and family responsibilities.

La’Shawn Allen-Muhammad of the Central Brooklyn EDC lauded city’s Brownsville Plan and the state’s Vital Brooklyn plan as worthy investments in Brooklyn’s infrastructure, but said Brooklyn’s low-income neighborhoods need more “investment in people.”

Many organizations in the borough, she said, know how to help low income entrepreneurs navigate many hurdles to new business formation and begin generating revenue, but there’s not enough funding to help everyone who needs it.

She cited her organization’s O.W.N. Brownsville initiative, a COVID-19 response effort which she said emphasizes “ownership, wealth-building and networking.”

“We are not funded to run a full-out program,” she said.

The panel also featured two entrepreneurs who have benefitted from investment in such programs: Ras Omeil Morgan, who created the health food truck iaRas iTal, and Latoya Meaders of Collective Fare, a Brownsville-based education and catering company operating out of Brownsville Community Culinary Center (BCCC) that has made use of grants and partnerships to pivot to an emergency food service during the pandemic.

“We start our side hustles, they grow into businesses, they grow into magnificent things with the right guidance, the right partnerships and the right resources,” Meaders said.