She may not call herself a feminist, but Ruchie Freier is smashing the patriarchy in Hasidic Brooklyn

BORO PARK – “This is a universal story of women’s empowerment that takes place in a very particular setting. We’re all fighting in some way in whatever communities we’re in,” filmmaker Paula Eiselt said. “This is a really powerful organization. They’re really breaking the ground for the next generation to come.”

As women across America fight new battles over their rights and run for office in unprecedented numbers, they are also stepping into new roles in one of the country’s most traditional religious groups: Brooklyn’s Hasidic community.

A new documentary, 93Queen, follows a central figure in challenging that community’s patriarchy from the inside, Rachel “Ruchie” Freier. Freier, the first Hasidic woman elected to the civil court in New York, is also the founder of an all-female voluntary ambulance service to assist women in Boro Park called Ezras Nashim (translates as Women’s Help).

The documentary follows her throughout the establishment of the service, which began six years ago when Frier sought to join Hatzolah, voluntary Emergency Medical Services (EMS) corporation serving the Hasidic community in Brooklyn. Created in 1969 to improve medical response in the Williamsburg community, which at the time had response rates of about half an hour for 911 calls, Hatzolah is now a community powerhouse and the largest voluntary EMS corporation in the world.

And it’s comprised of only Jewish men.

When Freier went to inquire, she was told women were not allowed. But Freier wouldn’t take no for an answer, and in 2014 Ezras Nashim, comprised only of Jewish women became a reality, with the main mission to respond to emergency labor and other OB/GYN emergencies, where care by female paramedics may be more welcome by the patient.

Ezras Nashim primarily operates in Boro Park and complements 911 and Hatzolah. If Hatzolah of Boro Park responds to 17,000 calls annually, Ezras Nashim is used by many pregnant women in Boro Park, and NYC’s neighborhood with the highest birthrate in NYC in 2015 was Boro Park, then that means the entirety of Boro Park has emergency services on the tip of its fingers.

Filmmaker Paula Eiselt’s documentary is the inspiring, and complicated, story of a woman who in the most literal sense challenged the patriarchy — but who doesn’t consider herself a feminist, and who says she’s at peace with a world of deeply traditional gender roles.

The documentary, 93Queen, premiered on July 25 (and on PBS on Sept. 17). The name 93Queen comes from Ezra Nashim’s call code given by the FDNY. The code, 93Q, depicts the women at Ezras Nashim perfectly, Eiselt told Bklyner.

“I just thought it was fantastic because it has ‘queen’ in it and Ruchie is a queen; they’re all queens,” Eiselt said. “They have that female empowered word in their call sign which I felt was quite perfect.”

The community’s first reaction, in the film, is skeptical: Rabbis were reluctant to endorse it. But Freier found plenty of Hasidic women who shared her vision — and wanted to become EMT’s.

Some of their male rivals still resent them.

In the film, Eiselt notes that Hatzolah bans its members from speaking to the media. We reached out to them three times but did not get a response. But, Eiselt did find one member willing to speak with her anonymously. Though his face was not shown in the film, he spoke about how no woman can ever match Hatzolah’s response time and that a woman’s place in Judaism is her home.

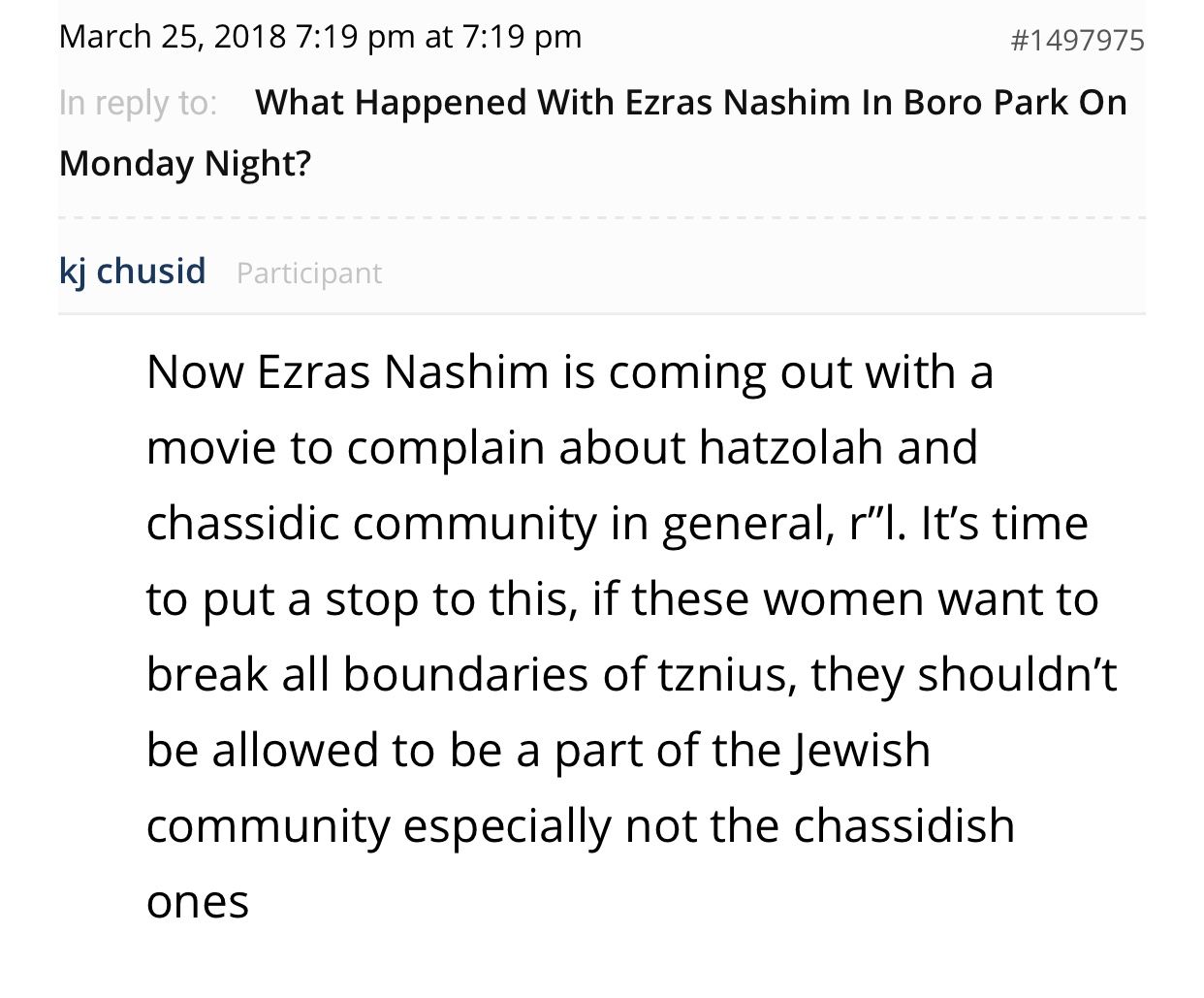

You can find some of that unvarnished sexism in the comments section of the Yeshiva World, a leading Orthodox Jewish publication. Its community section includes several threads related to Ezras Nashim’s service. “What Happened With Ezras Nashim In Boro Park On Monday Night?” “ANOTHER Ezras Nashim Horror Story?!”

The disputes in those comments are on very traditional grounds. One commenter pointed out that many people who have a problem with Hasidic women running an organization in any circumstance. Others pointed out that if Hatzolah had allowed them in its organization, they wouldn’t have to.

Eiselt describes the women in the film as “smashing the patriarchy in their community.” In the film, however, Freier says that these women are not feminists, “they are far, far, far from that.”

“Feminism is when a woman wants to be equal to a man or wants his job,” Freier says in the film. “I’m very, very happy with my role as a woman.”

In fact, once Ezras Nashim was created, Freier made the decision of not allowing single women to join.

“Having single women is controversial,” she says in the film. She didn’t want to be shunned by the community. Making that decision itself was very controversial. Several Hasidic women had a problem with it, and one EMT even resigned from Ezras Nashim. Though Eiselt doesn’t agree with “that notion of feminism, personally,” she does understand where Freier is coming from.

“This isn’t a black and white story. This is a very complex story,” Eiselt said. “Ruchie is complicated, they’re complicated, and I think feminism is really complicated.”

“This is what smashing the patriarchy looks like in the Hasidic community. The way feminism looks there is not the way feminism is going to look in hipster Brooklyn… in other communities and other countries.”

“I think this film puts forth a really nuanced and complex model of progress a community can discuss and embrace. These women should be supported especially by other women.”

Eiselt also noted that there is no single Hasidic community, so there’s no way of knowing if all Hasidic women are becoming more confident and are able to say no.

“There are so many types of Hasidic people. The ones in Williamsburg are different than the ones in Boro Park,” she said. “There are different sects and customs.”

Despite the hardships, Freier is not planning on quitting any time soon. Ezras Nashim is working to get bigger and better to serve the communities they love the most.

“It was really important for me to give Hasidic women a voice and platform,” Eiselt said. “There are a lot of stereotypes out there and misconceptions. I feel really lucky that I was able to give them a platform to say this is who they are on their own terms… and to humanize this community that’s often seen as mysterious.”

You can reach Ezras Nashim at 718-232-1300