Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead: “As Much About Theater As It Is About Shakespeare”

RED HOOK – The Cave Theater Company wasn’t planning a site-specific production of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead when they arranged to perform Tom Stoppard’s 1966 comedy at the Waterfront Museum in Red Hook. But the venue, a rescued barge docked at 290 Conover Street, certainly lends a frisson to one of the show’s signature lines.

“Our intention wasn’t to put in on a barge to begin with,” said director James Masciovecchio. ”We were looking for a non-traditional performance and came across this space that’s beautiful. It’s exactly what we were looking for, so now we’re on a barge. How cool is that?”

To avoid spoilers, this article will leave aside any more explicit references tying the play to the venue. But that textual reference is far from the only way Masciovecchio exploits the singular setting of Cave’s production.

Stoppard’s play famously takes two minor characters from Shakespeare’s Hamlet and brings them to center stage. “It’s a play that’s as much about theater as it is about Shakespeare,” Masciovecchio said. He cites a line where Rosencrantz shouts, “Fire,” riffing on the adage that free speech doesn’t give license to yell fire in a crowded theater. It’s one of many instances when actors remind the audience that they are watching a play. Many of the characters in the play are actors—as in the original Hamlet, they are performing a play within a play. (And, as Stoppard’s work literally re-stages parts of Shakespeare’s original, Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead offers a play within a play within a play.)

Cave Theater’s staging turns Stoppard’s self-conscious theatricality on its head, because in this production, there is no stage; all the action takes place in the middle of a single room—no sets or props—with the audience seated around the performers. But the barge puts yet another twist on that, as the boat gently rocks as other ships sail past outside, and the creaking of the old wooden craft mixes in with the recorded sound effects. In a play where no one ever knows what’s truly real and what’s false, or even if they are alive or dead, these ambiguities are a very clever riff.

That aspect of the work makes it an inspired choice for this company. Masciovecchio explained that Cave’s aesthetic “focuses a lot on the storytelling aspect, and the shows have some kind of hook where we’re letting the audience in on something or showing them behind-the-scenes machinations of it.”

He cited a production of Gruesome Playground Injuries, where the actors applied makeup and prosthetics on-stage to depict the titular wounds suffered by the characters. “We try not to do things that are that realistic from the get go because you can always go see a movie or watch a TV show,” said Masciovecchio.

When Stoppard’s play debuted in 1966, it challenged many of the prevailing notions about how a play could be structured. At its premier, Masciovecchio said, “no one knew what it was.” The audacity of the show provided much if its appeal, but because the work broke new ground, much of what was ingenious in the original production is now commonplace.

That makes Stoppard’s language crucial to any modern production of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern; if the cast cannot conjure a rhythm that highlights the playwright’s wordplay, it falls flat. Since not much happens in the show, everything depends on what is said.

Cave Theater’s production benefits from an absolutely stellar performance by Arshia Panicker in the central role of The Player. Crackling with energy, she exhibits a sarcastic wit that foregrounds the comedy of her lines without neglecting the serious existential themes Stoppard uses them to express.

Her frequent foil is David Hernandez III in the double role of Gertrude and Alfred, one of many in the cast who is cross-gendered. Hamlet is played by a woman, Esther Ayomode Akinsanya, and Ophelia by Garrett K. Lyons.

These gender reversals barely register, proving the quality of the actors’ performances. Hernandez takes it a little further. As Alfred, an actor in The Player’s company, he plays a man often commanded to act as a woman in the play-within-a-play.

Hernandez, in a scraggly beard and on-again/off-again skirt, provides an impressive depth to the character with a performance that consists mostly of facial expressions, whimpers and nervous laughter. A pornographic dumbshow in the second act featuring Khalid “DJ” Bilal, who doubles as Claudius and a Tragedian, is the comic highlight of the evening.

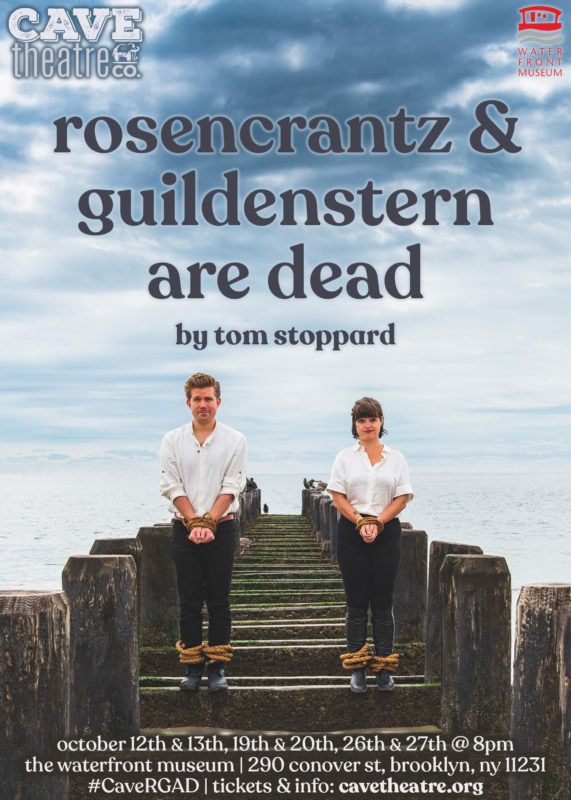

Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead

Friday and Saturday at 8pm (October 19, 20, 26 and 27)

The Waterfront Museum, 290 Conover Street, Red Hook

Tickets available online ($30)