Report: With or without Industry City rezoning, Sunset Park has a housing crisis

As City Councilmember Carlos Menchaca faces off with developers and his own colleagues over the plan to rezone Industry City, affordable housing advocates warn that the rising rents, gentrification and displacement that the plan’s opponents fear it could bring to the neighborhood are already well underway thanks to a severe housing shortage.

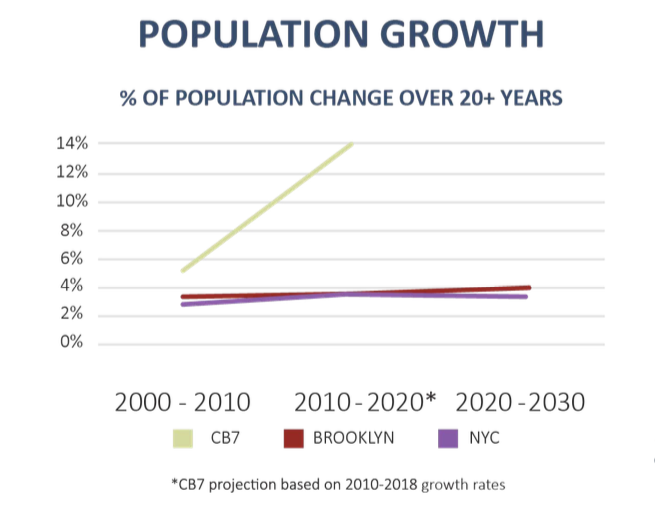

The population of Community Board 7 (CB7), which encompasses Sunset Park, increased by over 17,000 residents between 2010 and 2018. Meanwhile, the predominantly Latinx and Asian neighborhood saw a net loss of more than 3,700 housing units, according to a new report from the nonprofit Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC).

“For many decades, little to no investment in new housing development occurred in Sunset Park, even while the population of the neighborhood continued to swell to welcome new immigrants,” the report reads. “This has contributed to severe overcrowding in the neighborhood, placing Sunset Park in the top 10% citywide.”

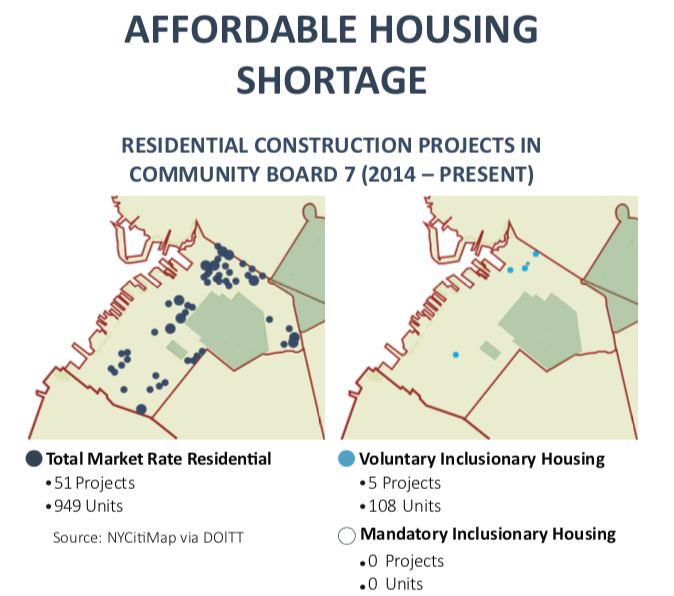

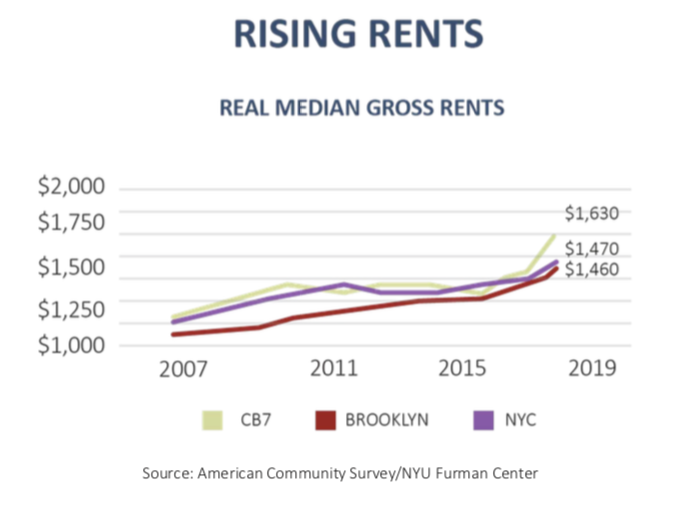

Only about 1,000 new housing units have been built in CB7 since 2014, and only 80 of those units are affordable. Median market rate rents in the area have climbed from $1,230 in 2006 to $1,630 in 2018, and incomes haven’t kept pace. Just over 30 percent of Sunset Park residents are severely rent burdened, meaning they spend over half their income on housing.

“Gentrification is really a convergence of low-income populations experiencing extraordinary rent increases, which leads to displacement,” said Matthew Murphy, executive director of the NYU Furman Center. “Sunset Park doesn’t get openly discussed in the same way as some of these other neighborhoods, and I think it needs to be because it is an affordable housing issue.”

The dearth of new affordable units may be traced to the neighborhood’s 2009 rezoning, when the Bloomberg administration declined to map Mandatory Inclusionary Housing — which requires a minimum number of affordable units in new residential developments — despite pressure from community organizations like FAC.

The city instead mapped Voluntary Inclusionary Housing in the area, offering developers a chance to construct higher density buildings than would otherwise be allowed in exchange for a minimum number of affordable units.

Only five Sunset Park developments have taken advantage of the voluntary program since 2014.

“We see the impact of that. Five projects, a handful of affordable housing sites,” said Michelle de la Uz, executive director of FAC, adding that targeted rezonings should be considered in Sunset Park to trigger MIH. “It’s a real opportunity to address some of the community’s needs, and quite honestly, do it faster than the 100% affordable housing projects can do.”

But zoning changes in New York City are contentious, and carry with them displacement concerns of their own, as the Industry City battle shows. As the city approaches its current zoning capacity — about 12 million — it’s important that the burden of absorbing more residents doesn’t fall entirely on lower-income communities of color, according to de la Uz.

“We want to see MIH used on a broader scale in a number of communities, not just Sunset Park,” she said.

The report proposed some creative solutions to the housing shortage, such as combining municipal buildings with affordable housing, an experiment that’s currently underway at the Sunset Park Library & Affordable Housing Project, converting industrial land for residential use, and remediating brownfields — unused sites deemed potentially contaminated by the EPA — for affordable housing developments.

De la Uz would also like to see the city provide tax credits to homeowners who rent apartment units at below-market rates, and to fully implement its delayed Neighborhood Pillars Program, which provides loans to nonprofits purchasing multi-family properties to preserve their affordability.

“I know it’s tough to talk about government financing at this moment in time, given COVID and its impacts,” said de la Uz. “But low interest rates, capital budgets, prices coming down. That’s when honestly we should be thinking about acquiring assets that might be vulnerable.”