Redistricting Is A Partisan Nightmare – Can New York’s New System Do It Better?

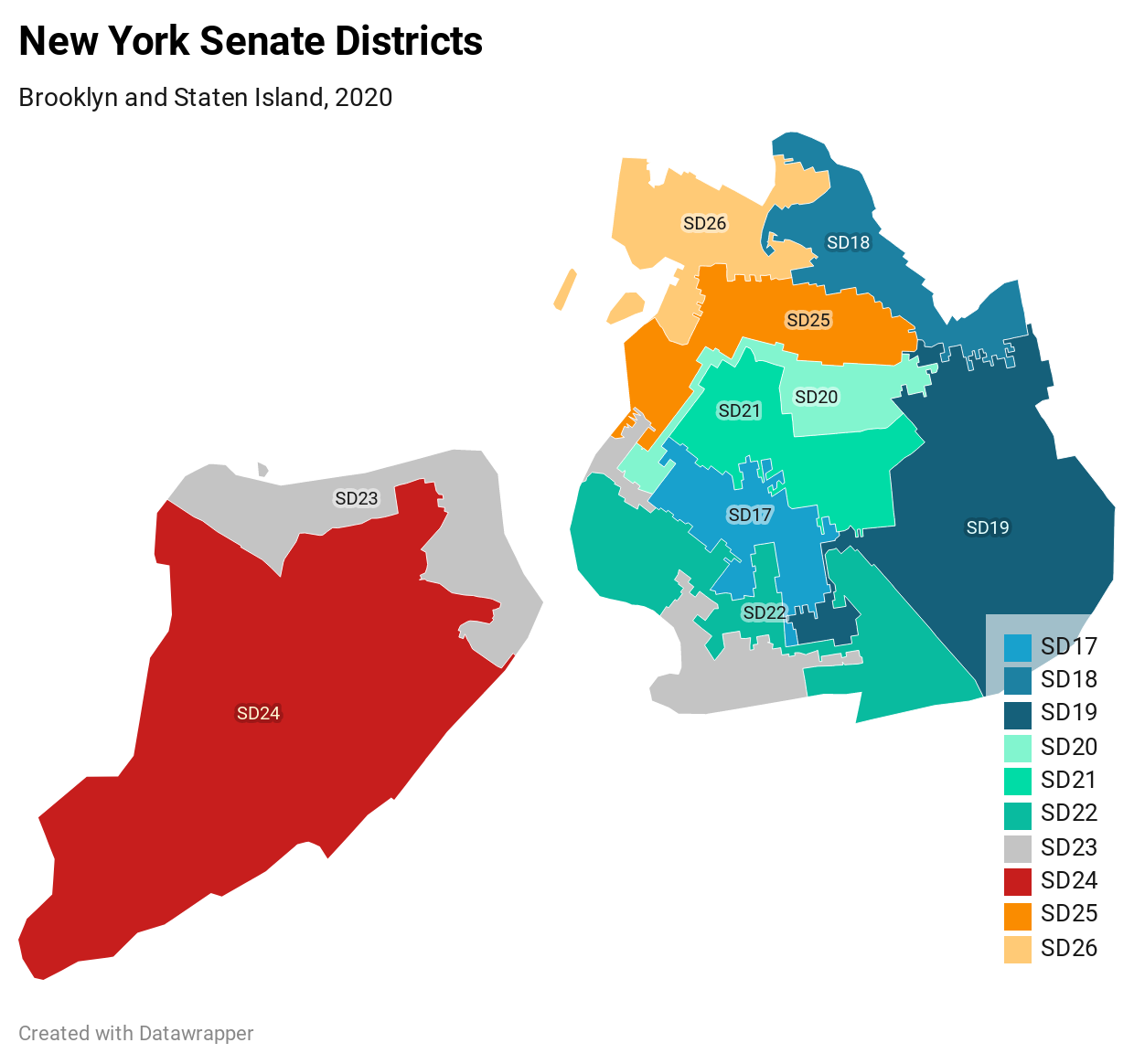

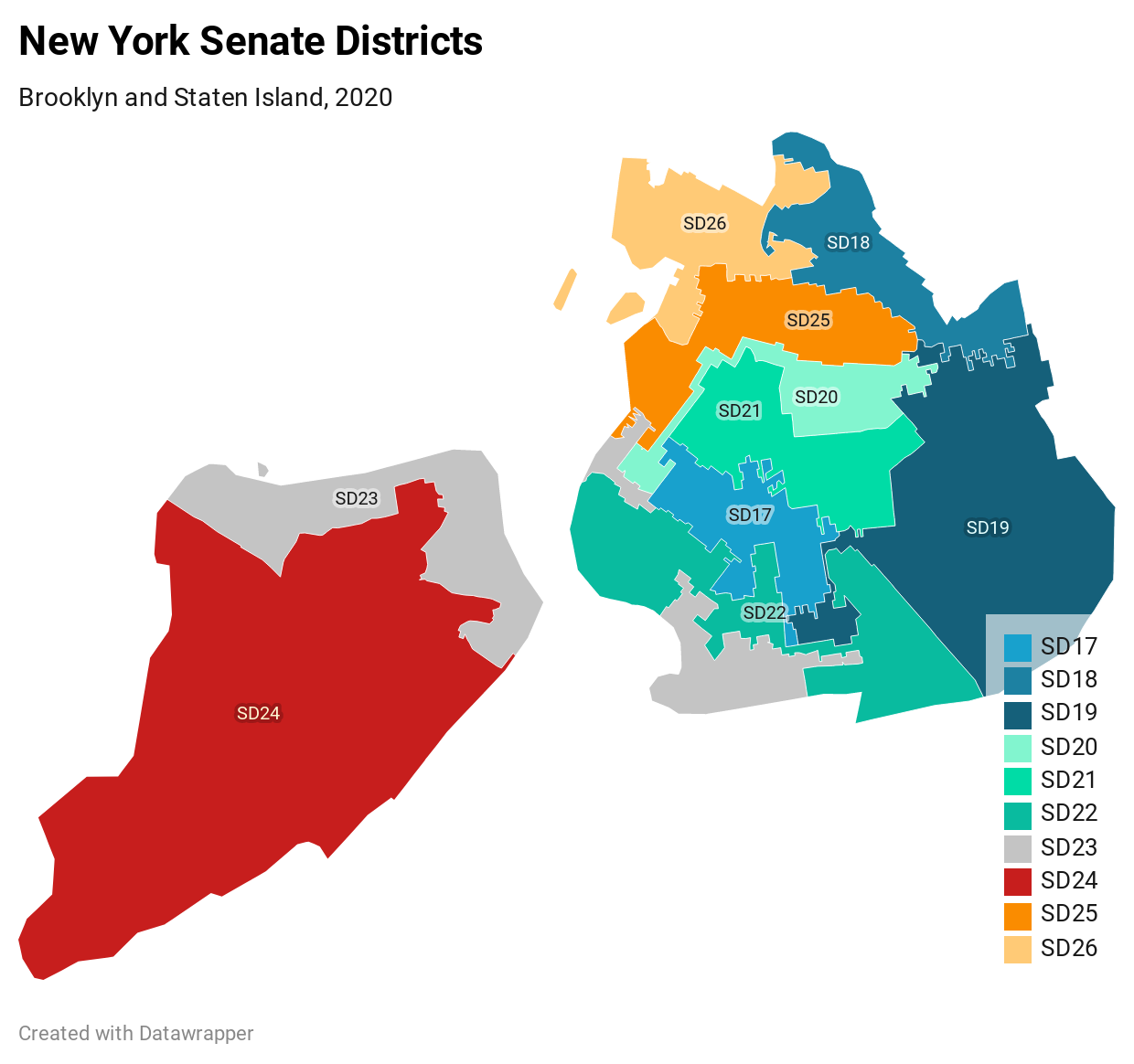

When you look at the map of State Senate districts that crisscross Brooklyn, what shapes do you see? Does Senate District 20, which winds its way from Brownsville to Sunset Park, look more like a backhoe or a bioluminescent fish? Does the bizarre tail, sometimes no more than a block wide, that connects Sheepshead Bay with the rest of Senate District 19, bring to mind a yo-yo or a mini-submarine? And does neighboring Senate District 22 evoke a scorpion’s tail or, as a friend recently suggested, “someone with a mullet getting a bikini wax”?

This game, in which oddly-shaped legislative districts are turned into Rorschach tests, is not new. In 2012, when New York’s current lines were drawn, the good government group NYPIRG awarded its “Salvador Dali/Pablo Picasso Award” for creative gerrymandering to five districts across the state, which were christened with names like “The Splattered Bug of the Bronx” (SD34) and the “Long Island Lobster Claw” (AD13).

“A district that looked like Abe Lincoln riding a vacuum cleaner,” said Blair Horner, NYPIRG’s Executive Director, referring to the winner of the group’s 2002 contest, “was something that people could see, and really underscored the political nature of how boundaries are drawn.”

Redistricting

Redistricting, the process of drawing congressional and state legislative boundaries that occurs every decade after the Census in all 50 states, has long been a highly partisan affair. New York is no exception. In 2014, voters approved a state constitutional amendment that created a new redistricting commission, with hopes of enabling a fairer, more transparent process. But though its members have yet to meet, the Commission is already being buffeted by challenges, ranging from Coronavirus and President Trump’s assault on the Census to a changing local political calendar and even the resignation of one of the Commission’s members.

For several decades, New York’s state legislature oversaw the redistricting process directly. Over time, a de facto arrangement emerged: Senate Republicans drew maps that helped them maintain their control in the chamber, in exchange for allowing Democrats to draw maps cementing their hold on the Assembly. At the same time, state courts became progressively less willing to challenge the constitutionality of the legislature’s distorted maps.

The current Senate map is the clearest illustration of these partisan priorities. According to a 2016 analysis by redistricting experts Todd Breitbart and Jeffrey Wice, “almost all upstate districts are underpopulated, and every New York City district is overpopulated, with the cumulative result that the city is apportioned one district less, and the upstate region one more, than the numbers of districts that would be proportional to their respective shares of the total state population.”

The analysis by Wice and Breitbart, both of whom worked under state Democrats on earlier redistricting efforts, identifies other problems, too. Black and Latino communities on Long Island are systematically split. The requirement that districts be compact is consistently ignored, as is the requirement that county boundaries serve as the basis for drawing districts. Senate District 34, the aforementioned “Splattered Bug,” was extended into Westchester to create a plurality of white voters, and to avoid the Latino majority that would have resulted from drawing a district entirely within the Bronx.

!function(){"use strict";window.addEventListener("message",(function(a){if(void 0!==a.data["datawrapper-height"])for(var e in a.data["datawrapper-height"]){var t=document.getElementById("datawrapper-chart-"+e)||document.querySelector("iframe[src*='"+e+"']");t&&(t.style.height=a.data["datawrapper-height"][e]+"px")}}))}();

Brooklyn’s map has plenty of its own peculiarities. Senate District 22, which cobbles together neighborhoods from Bay Ridge to Marine Park, “was obviously given its bizarre shape to link together as many Republicans as possible,” said Breitbart. At the time, the seat was held by Republican Marty Golden, who eventually lost to Democrat Andrew Gounardes in 2018. Meanwhile on the Assembly map, Bay Ridge, traditionally a Republican stronghold, is split into three different districts.

Just north, Sunset Park is split amongst four different Senate districts, including one that runs all the way to Brownsville. “The absurd tail of Senate District 20,” Breitbart contends, was created to keep Latino voters in Sunset Park out of any of the adjoining districts. On the Assembly map, the neighborhood is covered by just two districts.

The state’s current congressional districts, which unlike their state counterparts are almost perfectly balanced population-wise, were drawn by a court-appointed magistrate after Senate Republicans and House Democrats failed to agree on a map.

Reform has been slow to come.

In 1978, the state created the Legislative Advisory Task Force on Reapportionment and Demographic Research (LATFOR), which appointed two members of the public to serve as co-executive directors, the first time non-legislators had oversight over the process. LATFOR was also among the first redistricting entities to make use of digital mapping technology. Nevertheless, the entity remained under the thumb of partisan influence.

Then, in 2009, a group calling itself New York Uprising, led by 84-year-old former New York City mayor Ed Koch, launched an initiative calling on state lawmakers to “sign the pledge” to support reforms that would create nonpartisan redistricting. Senate Republicans, in the rare position of being the minority at the time, signed on quickly, to the chagrin of Senate Democrats, whose support came more slowly.

But after retaking control of the Senate in the fall 2010 elections, many Republicans balked, insisting Koch’s reforms required a constitutional amendment rather than simple legislative action. Governor Andrew Cuomo, who was elected the same year and who had campaigned in support of reform, threatened to veto any “hyper-partisan” maps created by the legislature. Eventually, a deal was struck: leave the old process in place for the 2012 redistricting process, in exchange for a constitutional amendment that would create an independent panel to oversee redistricting in 2022 and beyond.

The Independent Redistricting Commission

The Independent Redistricting Commission, as the panel was to be called, would be made up of 10 members: four appointed by state Democrats, four appointed by state Republicans. The remaining two commissioners would be selected by the first eight, and could not be registered members of either major party. The maps produced by the Commission would have to be approved by the legislature. If state lawmakers rejected the maps, the Commission would have to create a second set. If lawmakers rejected those maps too, the legislature could draw the lines themselves.

Reform advocates were split over the proposal. Some entities, like Citizens Union and the League of Women Voters, supported the amendment. Others, including NYPIRG and Common Cause NY, criticized it as “loophole-riddled changes favoring politicians” at the expense of voters. Indeed, in 2014, a state judge ordered the state to remove the word “independent” from the ballot question that would go before voters that fall. “Not only can the legislature disapprove the Commission’s decision,” Judge Patrick McGrath wrote in his ruling, “but it can do so without giving any reason or instruction for future consideration of these new principles…. the Commission’s plan is little more than a recommendation to the legislature, which can reject it for unstated reasons and draw lines of its own.” In any case, in November of that year, 57.7% of New Yorkers voted to approve the amendment.

The Commission’s creation, however, is just the first chapter in an ongoing story. Earlier this year, the legislature named the first eight commissioners. The Democratic appointees include Eugene Benger and David Imamura, both attorneys at Debevoise & Plimpton; John Flateau, a professor at Medgar Evers College; and Elaine Frazier from the Capital Area Urban League. The Republican picks included former state politician George H. Winner Jr; Charles Nesbitt, a former Assembly Minority Leader; 2018 State Attorney General candidate Keith Wofford; and Ed Lurie, a former director of the New York Republican State Committee.

Perhaps predictably, the selections provoked swift backlash. Several activist organizations criticized the inclusion of only one woman and no Latinos amongst the group. “How could this happen in today’s day and age?” asked Jose Luis Perez, Deputy Legal Counsel for Latino Justice PRLDEF, at a joint legislative hearing last month. “It’s inexcusable.” In May, the group sent a letter to state leadership requesting the Commission appoint a Latino to at least one of the two remaining nonpartisan slots, and identified five potential candidates for the role.

The hearing brought to light several other outstanding issues. When the 2014 amendment was passed, New York’s state primary elections were scheduled for September, but last year the legislature voted to move them to June, screwing up the Commission’s timeline. Old language dating to 1894 — crafted to favor rural upstate counties at the expense of denser, immigrant-heavy downstate counties — inexplicably remained in the text of the state constitution, even though it had been declared unconstitutional in 1964. A 2010 law requiring state prison populations be counted toward the population of incarcerated individuals’ home counties, rather than the county where the prison is located, was not enshrined in the constitution, making its applicability for the upcoming redistricting unclear. The Senate had not been fixed at a particular number of seats, despite ample evidence that Republicans had previously used the creation of additional seats for partisan advantage.

A week after the hearing, state Democrats proposed another constitutional amendment intended to address these issues. The amendment quickly passed the Democrat-controlled legislature (like all amendments, it will need to be approved by the legislature a second time, and then by voters, before it is added to the state constitution. The governor does not have a formal role).

Senate Republicans, however, were furious, because the proposal also removes the complicated partisan vote requirements established in 2014. Under that plan, if the Commission’s members approve maps by a vote of 7-3 or better, and control of the Senate and Assembly are split, then only a simple majority in each house is necessary to approve the plan. If fewer than seven Commissioners approve a proposal, that proposal will need 60% of the votes in each chamber. If the Senate and Assembly are instead controlled by the same party, as will likely be true in 2022, then at least two-thirds of each chamber needs to vote to pass the Commission’s proposal.

The new Democratic amendment would lower those thresholds, to a simple legislative majority for a plan the Commission approves with seven votes, and to 60% for a plan the Commission approves with fewer. There are also changes to partisan voting requirements amongst the Commission itself, and in the appointment of the co-executive directors the Commission will eventually hire.

“It eliminates, frankly, minority participation,” asserted Republican Senator Thomas F. O’Mara, who represents parts of Western New York. “Already, the Democrats have in excess of a two-thirds majority in the Assembly. The Republicans in the Senate have greater than a one-third representation. However, if you drop the two-thirds requirement to 60%, then that takes away any real voice of the minority party in the Senate.”

One Republican-appointed Commissioner, Ed Lurie, went so far as to resign over the Democrats’ proposed changes.

“Short version is when Senator Ortt became Minority Leader I thought he should have an opportunity to appoint his own person,” Lurie said via LinkedIn message, when asked why he resigned. “Longer version is the Democrat Majority doesn’t want it to work. Before one decision was made by the Independent Reapportionment Committee they already started amending the law to weaken its effect.”

Senator Robert Ortt, who replaced Senator John Flanagan as Senate Minority Leader in June, has since named Jack Martins, himself a former State Senator from Long Island, as Lurie’s replacement.

Civic society is again split over the best course of action; NYPIRG and Common Cause supported the amendment, while Citizens Union and League of Women Voters have released a statement in opposition, arguing that “changing redistricting midstream, in a highly rushed timeline and with no room for public input, would be disruptive and potentially damage public confidence in the process.”

Republicans also accuse Democrats of failing to release $750,000 in previously allocated funding to the Commission, preventing it from starting its work. Democrats contend that Commissioners don’t need the funding to meet and begin deliberations to fill the two remaining Commission slots, and that Senate Republicans have not completed the necessary paperwork regarding Martins’ appointment which, when filed, would allow for the money to be released.

Census & Pandemic Impact

Looming over this partisan dispute are the twin crises of the Coronavirus pandemic and Trump’s politicization of the Census, both of which have made it more difficult to get an accurate count.

The Census Bureau has asked Congress to extend its work deadline by four months, to account for delays caused by the health crisis. House Democrats included the extension in their most recent coronavirus relief package, but Senate Republicans have been reluctant to do the same. Meanwhile, in recent weeks President Trump has issued an executive order to exclude undocumented immigrants when Census information is used to apportion House seats to the states, and has instructed the Census Bureau to cut short its in-person counting by a month, ending on September 30th rather than October 31st.

Both changes, if they survive court challenges, would likely depress the count amongst the low-income, non-white and immigrant Americans that make up a sizable portion of New York’s population. Even before Trump’s orders, New York was predicted to lose at least one Congressional seat. An undercount could do further damage.

In the meantime, experts like Wice, who is an adjunct professor and senior fellow at New York Law School, are working to educate New Yorkers on the impact redistricting can have on their lives. In November, Wice helped launch the law school’s Census and Redistricting Institute, which plans to operate public mapping project that would allow students, reporters, and the general public to obtain free software, data and training to draw and analyze their own maps. Those efforts will ramp up next summer when the redistricting process is more fully underway. For now, though, Wice says New Yorkers should be focused on ensuring their communities are counted as accurately as possible in the Census.

“That’s going to be a process that we need all hands on deck to work on,” said Wice.