Off Their Plate is Helping Provide a Hot Meal — And A Paycheck — To Those On The Front Line

Off Their Plate is working to ease the overwhelming burden placed on both restaurant and hospital workers by the coronavirus pandemic, one $10 meal at a time.

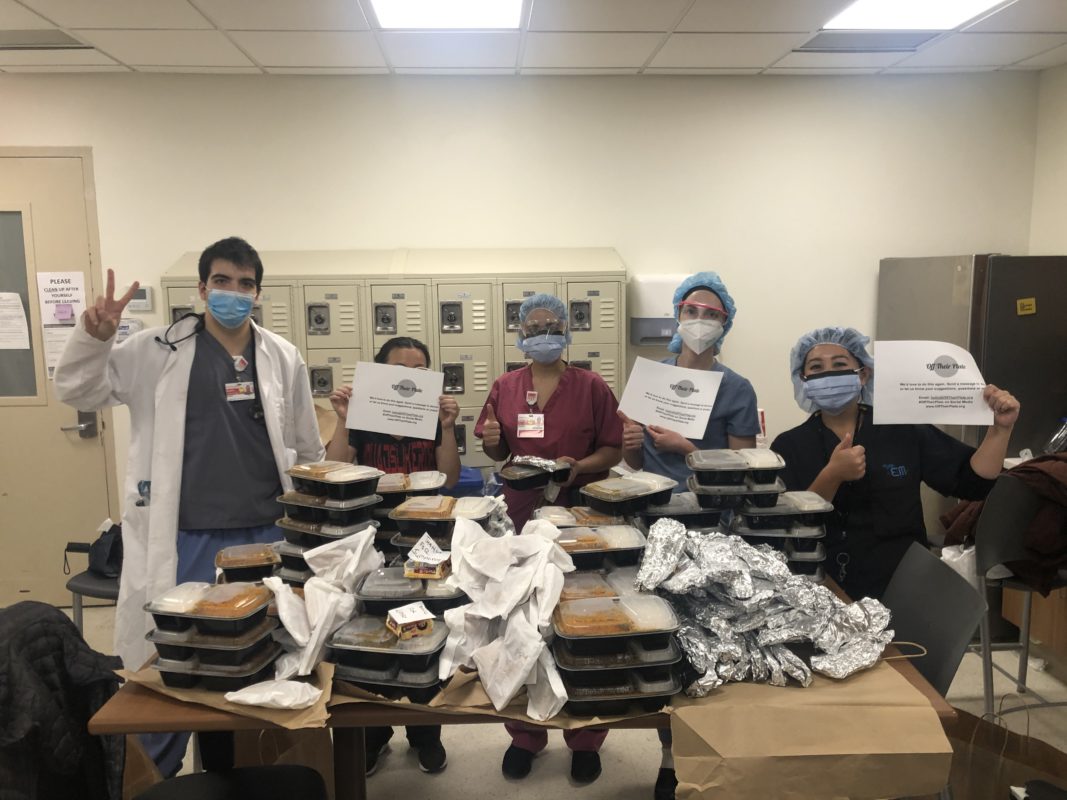

Started in Boston in mid-March by founder Natalie Guo, the volunteer-run national grassroots organization has been delivering thousands of what they call “hero meals” to frontline healthcare workers across the U.S. by partnering with local restaurants and hospitals in over nine cities, from Los Angeles to New York.

“Our work at Off Their Plate is about the human impact of the pandemic,” Guo said on Friday. “We exist to support those on the dual frontlines of this unprecedented crisis – our healthcare workers healing the sick, and our restaurant workers fueling the fight.”

The New York chapter, which launched just one week after the organization kicked off in Boston, has already delivered over 10,000 meals to hospital teams across the city, partnering with restaurants like the Lower East Side’s Golden Diner and Thai spot Fish Cheeks. Their rapid growth was helped along by their partnership with Chef Jose Andres’ hunger relief organization, World Central Kitchen, which, as a 501c3, allowed Off Their Plate to begin processing donations. 100% of these donations provide economic relief to restaurant workers, who in turn prepare fresh meals for hospital workers. In the next week alone, they aim to donate another 10,000 meals.

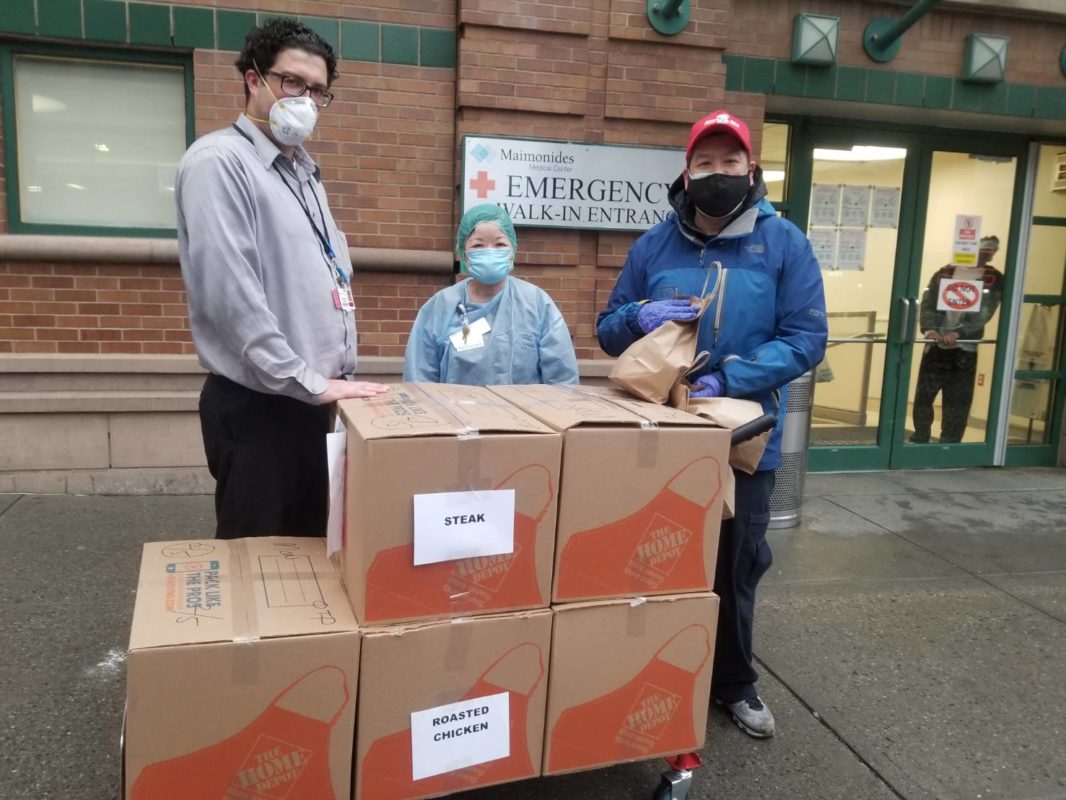

New York organizer for Off Their Plate, Leah Wong, explained that the New York team has recently begun focusing mainly on hospitals that are currently underserved, particularly public or community hospitals that may not be receiving the same level of funding as larger, academically affiliated institutions, such as Mount Sinai. At hospitals getting an influx of donations, the administration will collect and centralize inbound donations, explained Sherman Leung, New York City Healthcare Lead for Off Their Plate. The administration will then order the meals, and coordinate delivery to branch hospitals.

At certain, more underserved hospitals – like Brooklyn’s Interfaith Medical Center and Maimonides Medical Center – workers still have to take care of their own meals. That’s exactly what the organization has been working to address, Wong said.

“The last thing we want our hospital frontliners to have to do is worry about bringing dinner when they’re also saving lives,” said Wong.

Wong believes that a good meal can not only boost workers’ morale, but help restore a sense of normalcy to their lives – especially for those forced to live separately from their families for the foreseeable future. The meals go to attending physicians, but also to residents, nurses, technical staff, and all other frontline workers.

“After weeks of fighting this pandemic the best we can while some of our own are also sick, having a hot, healthy plate of delicious food with one other while decompressing for a moment greatly helps raise morale and keeps us smiling,” Dr. Minh Evans, Emergency Medicine Chief Resident at NYP Brooklyn Methodist Hospital. “It also means a lot to us healthcare workers to support back our local neighborhood restaurants that we miss enjoying in person.”

To keep these frontline workers fed, Off Their Plate turned to another hard-hit community: restaurant workers, many of whom, if they haven’t been laid off already, are at risk of losing their jobs and associated benefits.

Since many local restaurants are not accustomed to preparing meals at such a large scale, Off Their Plate operates by setting recurring orders with the same restaurants. That model helps restaurants plan better, and allows them to predict how much they’ll need to order on a weekly basis to keep up with demand. On average, each order consists of about 100 meals.

One benefit of this system, Wong said, is that it lowers the barrier to entry for smaller restaurants. Otherwise, “you might lose out on finding a good local restaurant that wants to get involved because they can’t step up to the challenge,” she said.

Off Their Plate also orders meals at a set price — $10 a meal. That price ensures that each restaurant is “contribution margin positive,” explained New York City Restaurant Lead for Off Their Plate, Katherine Degnen. That means that they won’t lose money from their partnership with Off Their Plate, and can still pay their workers and cover rent and other costs.

Another distinctive feature of Off Their Plate is the fact that 50% of the donations restaurants receive is directed to their staff, “often those who are undocumented or otherwise unable to subsist on unemployment” Wong told us over email. That agreement operates mainly, Wong, said, “on good faith,” though they try to focus on building sustainable and long-lasting relationships with owners, instead of rapidly signing on new partners, to ensure that they can trust each restaurant to uphold the agreement. And, while anyone can apply for partnership, Off Their Plate first makes sure that each potential new partner is on board with their health and sanitation protocols, which they’ve created in tandem with a group of experts in medicine, science, and food preparation. They’ve also begun doing virtual kitchen tours via Zoom to make sure each restaurant is sticking to these protocols.

Thus far, Off Their Plate only has one restaurant partner in Brooklyn, but is in discussion with a few more.

Bryan Chunton, Zen Yai’s owner, has already been able to bring four more workers back on the payroll after he was forced, at the beginning of the pandemic, to let most of his 20-person staff go. Before they signed on with the organization, it was just him, the chef, and one other staff member, he said.

Chunton had tried to apply for a loan from the PPP – Payment Protection Program – as soon as the application went live, but the application crashed, and he was forced to wait two or three days before he could even submit his application. At that point, he said, “all the money ran out.” It’s been several weeks, and, like many businesses who applied, he has yet to see a single cent.

“I think I heard all the big guys got it – Shake Shack, all those people,” Chunton said. Still, he said, “Off Their Plate helped us, so whether we get the PPP or not, I think Off Their Plate will help us to survive until this is over.”

Restaurants interested in partnering with Off Their Plate can sign up here. Individuals and organizations interested in supporting Off Their Plate with a financial contribution can do so here.

The article had mistakenly attributed the statement about hospital administrations collecting and centralizing donations to Katherine Degnen. It has been updated to show that it was actually from New York Hospital Lead, Sherman Leung.