NYC’s Small Landlords of Color Among Those Battling for Survival Amid Rent Moratorium

By Greg David, THE CITY. This article was originally published by THE CITY

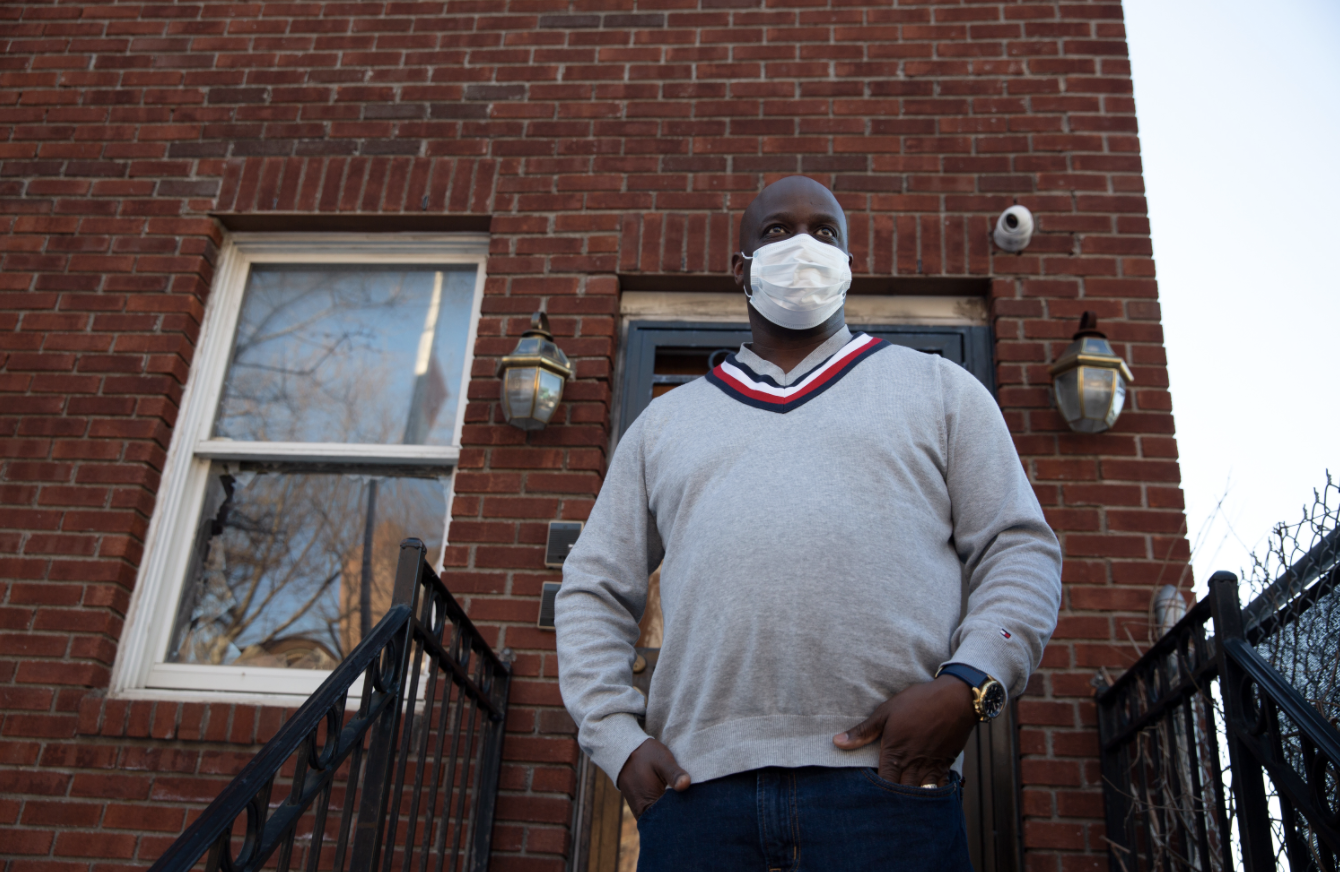

In 2019, Clarence Hamer bought a house and moved to upstate Harriman, turning the two-family home he had owned in Brownsville since 2007 into an investment property that he could one day leave to his son and daughter.

His plan blew up when the tenant who had moved into the unit he formerly occupied stopped paying rent in the summer of 2019. With the eviction moratorium in place, Hamer hasn’t been able to collect rent or proceed through the courts to have the tenant removed. He isn’t paying his mortgage on the Brooklyn building and says he expects to be foreclosed on when his bank eventually moves to collect what it is owed.

“I know I am in jeopardy of losing my home,” said Hamer, 46, “a home I was going to be turning over to my kids and it doesn’t seem like I am going to do that.”

While the plight of New Yorkers who have lost their jobs and have been unable to pay the rent has been in the spotlight of coverage of how the pandemic has upended the New York City economy, less attention has been given to the plight of small landlords, many of them people of color.

Some small landlords interviewed by THE CITY say they are desperate. While part of the problem can be traced to the pandemic, the landlords are also frustrated at being at the mercy of some tenants who stopped paying before the COVID-19 crisis.

At the same time, they say, officials seem oblivious to their plight.

“If government provides relief for tenants they need to provide some sort of relief for property owners,” said Sharon Redhead, a daughter of Caribbean immigrants who co-owns four small buildings in Brooklyn.

Avoiding a Repeat of 2008

The consequences for the city could be a repeat of the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, when a disproportionate number of homeowners of color lost their properties.

“We cannot come out of the pandemic where large rent arrears mean owners are in default in majority Black neighborhoods,” said Matt Murphy, executive director of the NYU Furman Center, a real estate research institute. “The last thing anyone wants to see is a repeat of the foreclosure crisis with a disproportionate impact on Black and Hispanic landlords.”

In 2007, 28% of Black New Yorkers owned their homes before falling almost three percentage points by 2014. Ownership still has not bounced back to the 2007 peak, according to Furman Center research. Hispanic home ownership peaked at 16.7% in 2007, fell almost two percentage points, but has recovered.

No data exists on the number of landlords of color in New York City. Research from the Urban Institute suggests that nationally 13% of owners of small properties with four or fewer units and Black and 15% are Hispanic, the largest percentage of owners of color of any housing segment.

‘We Have Bills to Pay’

Owners of small properties generally have more fragile finances than larger owners who often boast more diverse portfolios of rental units, Murphy noted. But many properties are listed as owned by limited liability companies, leaving no data to break down the differences.

Tenants of small landlords were also more likely to be affected by the pandemic downturn, research from both Furman and the Urban Institute shows. Early in the pandemic, Furman reported that 31% of renters in one- to four-family homes were vulnerable to losing their jobs, the highest of any category of housing.

Redhead operates a family real estate firm with her sister that owns four, four-story walk-ups in East Flatbush with a total of about 50 units, all rent stabilized. She traces her problems back to the 2019 changes in the rent regulation rules that limited the increase in rents after an owner renovated an apartment.

Since all her buildings were built before 1940 and many of the tenants have lived there for 20 years or more, it would cost $30,000 to renovate a unit when a resident moves, she says. The new law allows her to raise a typical $850 rent by $89, making renovation too costly.

The pandemic has increased the financial strain she is under because the number of vacancies has doubled to about eight. About 70% percent of her tenants continue to pay rent, while 15% are paying partial rent and 15% are paying nothing.

“I have tenants who aren’t working and haven’t missed a payment and tenants who are working who haven’t paid the rent,” she said. “We have bills to pay and whatever cushion we had has been used up.”

Costs Outpace Income

For others the situation is far more dire.

Hamer paid $450,000 for his Brooklyn home. His mortgage and expenses like property taxes and water bills push his monthly costs past $5,000. Since his tenant is not taking care of the property, Hamer says, he is also hit with weekly $300 sanitation tickets.

His upstairs tenants’ rent of $3,250 covers only about half his expenses.

Cynthia Brooks, a single Black woman in her 50s who works for a transit agency, brought a four-unit building in Brownsville in July 2014 for $520,000. She spent another $120,000 renovating it and rented one unit to a previously homeless family under a program where the city subsidizes the rent for a transition period.

The tenant’s rent payments were erratic, said Brooks, adding she gave them notice in December 2019 that the lease would not be renewed and they should move out at the end of February. But a judge allowed the tenant not to pay back rent, ordered her to make future payments and gave the tenant until June of last year to move out.

Aided by the eviction moratorium, the tenant stopped paying in May 2020 and won’t leave, she said.

Brooks said the tenant and her children have destroyed property and are so unruly that two of the other tenants have left. She doubts she can rent the empty units until her problem tenant leaves.

“The courts are closed, the (eviction) warrant is sitting on the sheriff’s desk and I am not allowed to evict,” Brooks said. “My lawyer has gone through all the hoops and the case just gets delayed and delayed.”

She can’t wait any longer.

“The situation I find myself in has been going on so long with no end in sight that I have been forced to put the building up for sale,” she said. “I have a couple of offers and soon I will have to accept one.”

A Lost Year

Landlords of color are at a particular disadvantage because they have been discriminated against by lending institutions for decades, their advocates say.

The Community Housing Improvement Association, a group that represents primarily nonprofit and smaller landlords, has been trying to convince banks to increase lending for minority landlords for the last two years, with limited success.

“It has not been easy,” said CHIP Executive Director Jay Martin. “The pandemic has cost us a year.”

One effort has been launched in Albany to help these owners. The second-ranking Democrat in the State Senate, Michael Gianaris of Queens, is pushing a $2 billion Housing Stability Relief Fund that would pay rent arrears for tenants in buildings occupied for small landlords.

Some tenant activists see that as a way to bridge the gap with landlords.

As Al Scott, president of the East New York Community Land Trust, recently told THE CITY’s NYC Rent Update newsletter: “People get scared when they hear ‘cancel rent,’ but the thing we have in common is whether you call it eviction or you call it foreclosure, that’s a form of displacement. Don’t let them separate us.”

A change of administrations in Washington may help give those landlords a voice.

Erika Poethig, then with the Urban Institute, drew attention to the crisis of landlords of color at a New York Federal Reserve Board conference late last year. She is now a member of President Joe Biden’s Domestic Policy Council.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who imposed the eviction moratorium, and Mayor Bill de Blasio, who supports it did not respond to requests for comment on the plight of small landlords.

‘Who’s Going to Step In?’

CHIP’s Martin is among those calling for direct aid to these landlords, saying they have been put in an impossible position.

“Government is saying keep providing housing, figure out a way to pay your expenses and hold the tenant harmless,” he said.

The Furman Center’s Murphy agrees.

“One intervention that treats all housing the same is not good policy,” he said. “We need to have programs ready for small landlords since losing that generation of ownership is unacceptable.”

People needing affordable housing will be hurt too, small landlords say.

“Our tenants are immigrants, legal and otherwise,” said Redhead. “We are the ones providing affordable housing in our neighborhoods. If owners like me go under who is going to step in and rent to these people?”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.