New York’s Rents Drop as Vacancies Increase. Could Rent Regulation be Next Thing to Fall?

By Greg David and Rachel Holliday Smith, THE CITY. This article was originally published by THE CITY

Since the pandemic struck the city, mover Dan Menchini has picked up the belongings of 200 New Yorkers and put them in storage as they left town.

The customers, he said, either allowed their leases to lapse or talked their landlords into terminating their leases — but weren’t ready to decide on a permanent place to live.

“This has never happened before,” said Menchini, the owner of U Santini Inc., a 90-year-old moving company in Brooklyn. “They send me their keys and say, ‘Pack it up and put it in storage and we’ll figure it out later.’ There are so many people in flux.”

With thousands or more leaving New York, rents are dropping for the first time in years, and residential housing experts say the decline will continue for the rest of 2020. What happens after that is unclear to even the experts.

Meanwhile, vacancy rates are increasing — and if the trend holds, New York’s system of rent regulation could be endangered since it is based on a housing emergency defined as a vacancy rate of 5% or less. A key official vacancy survey is expected to begin next year.

“I view the summer as the spring market that never took off because of the shutdown,” said Jonathan Miller, chief executive of Miller Samuel and the author for decades of the Elliman reports that track the region’s residential markets. “Then after Labor Day all bets are off. I think the rental market hasn’t found its level yet.”

A Downward Trend

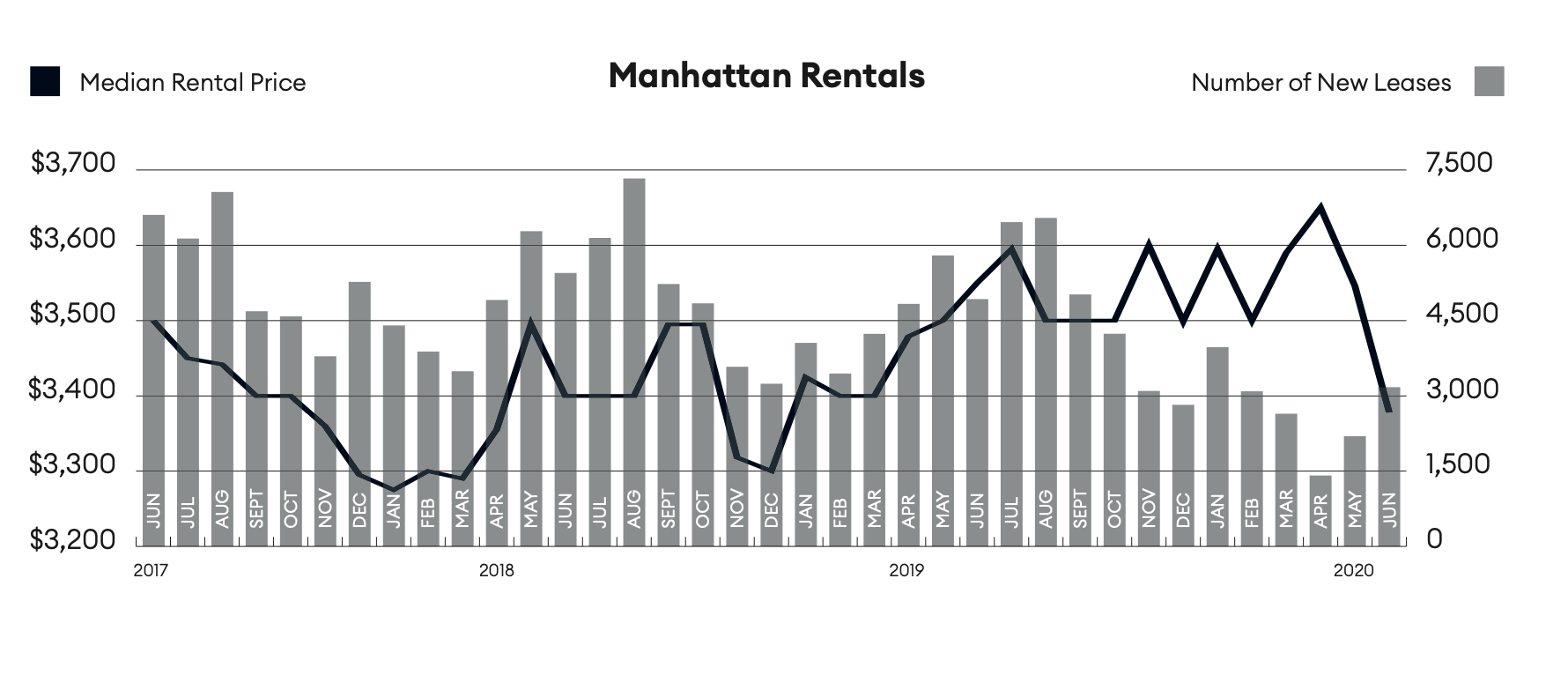

Recently released numbers show a dramatic change in the market where rent increases once seemed relentless.

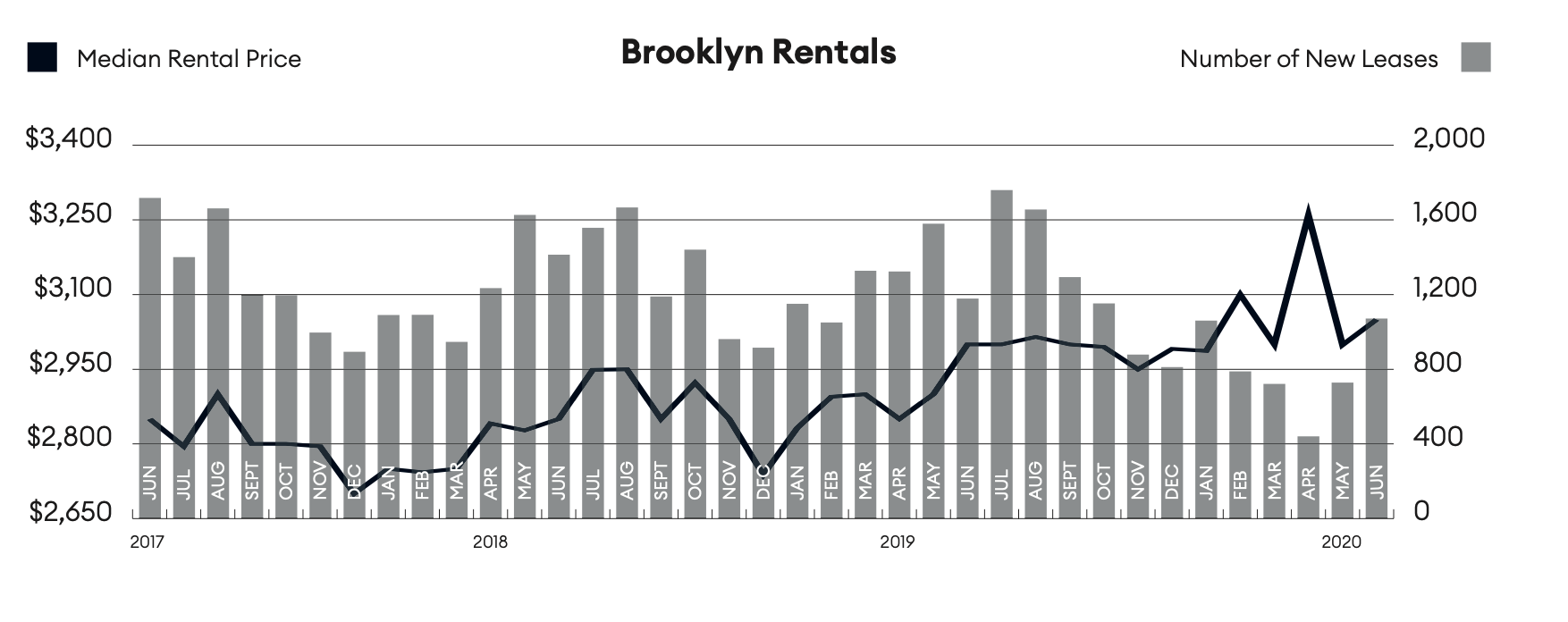

The median rent in Manhattan dropped 4.7% in June, the first decline since 2018 and reversing all the increases of the past two years, according to Elliman. Rents fell a little less in Brooklyn and by more than 5% in northwest Queens. The report doesn’t track The Bronx and Staten Island.

One-third of Manhattan rents were discounted from their asking price, by an average of 7%, according to data from StreetEasy.

The Manhattan vacancy rate, Elliman found, jumped 2 percentage points to 3.67%, a 14-year high.

The data is only available for new leases and significant concessions on lease renewals would also show declines in rent, Miller said.

Neither Miller nor Nancy Wu, an economist at StreetEasy, was willing to make a prediction of how much more rents will decline.

But Wu noted that many leases are expiring this summer which will translate into lower rents as demand falls and inventory rises. One factor: It isn’t clear how many college students will return with many classes exclusively online.

‘We Love New York’

The key, however, is the decision of many people to leave the city, either temporarily or permanently.

Sean Sullivan and his family made the agonizing decision to leave New York temporarily during the quarantine.

He and his wife, both attorneys, stuck it out working remotely with their 4- and 6-year-old kids in their Prospect Heights two-bedroom apartment until the end of May. That’s when the kids began refusing to go outside, unwilling to suit up with masks and gloves just to play on a small patch of sidewalk near their building.

“They felt a lot of anxiety,” he said. “It was just a lot.”

The couple debated leaving “for weeks,” he remembered. She was born and raised in Manhattan and he had lived in New York for more than 20 years. Neither wanted to flee the city “in a time of crisis,” he said.

Ultimately, they decamped to his in-laws’ house in Vermont. Now, they go on hikes every weekend, and the kids have room to run around. But they plan to leave Vermont in late August.

“We will be back,” he said. “We love New York.”

More and more, however, neighbors in their building in Brooklyn are moving away — for good.

The city’s population had been falling before the pandemic. After initially claiming declines reported by the U.S. Census Bureau were statistical blips, the City Planning Department in March conceded that population had decreased by about 85,000 people between 2017-2019.

Though no one has any data to back up the claim, experts generally agree that people have left the city during the pandemic in large numbers — but disagree on who those people are. Some believe that the move outs and concentrated among upper income families. Others say millennials have fled, most of them to move back in with their parents.

Burbs Boom

All agree suburban areas are benefitting as city residents move to buy homes or rent apartments. Mortgages rates below 3% have given many renters the means to buy.

Miller noted signed contracts in Westchester for home purchased soared 50% in June from the previous month. “On the ground, brokers in Westchester, Fairfield, Nassau and Suffolk have seen a tremendous inbound traffic from residents from the city looking to become first-time buyers,” he added.

Wu notes that while people are moving out across the city, the Manhattan market is the weakest because people no longer are interested in shared amenities like workout spaces that come with pricey rents and instead simply want more space.

That’s not what she expected: In March, she wrote a blog post noting that rents following the 2008 financial crisis declined the most in the boroughs outside Manhattan and among lower-cost apartments, and said she expected to see the same trend this time.

She now believes that interest in moving from Manhattan to Brooklyn and Queens might help bolster those areas.

Miller predicts rents will soon fall just as much in those boroughs and for lower-cost units because those areas and lower-income service workers who live there have been hurt the most in the economic meltdown.

‘Laundry Room is Deserted’

Developers know they have no choice but to cut rents if they are going to fill apartments.

Camber Property Group is beginning to market a 132-unit market rate apartment building on Starr Street in Ridgewood, Queens, and expects to offer two or even three months free rent to lure people to the building after cutting rents by about 5%. The total discount is almost 20%.

“It is the worst time in history to be leasing up units,” said principal Rick Gropper, said in a webinar on the market last week.

Renters know they have the leverage.

Monish Datta is hoping to find a better deal on rent in SoHo. The start-up vice president moved to the neighborhood just before the virus crisis and has watched his 60-unit complex turn into a “ghost town.”

“I never have to wait for the elevator,” he said. “The laundry room is deserted.”

He’s planning to ask for a decrease in his $3,800-a-month rent. If his landlord doesn’t go for it, he might break his lease. He’s seen a lot of good prices in listings elsewhere.

Joshua Maymir left Brooklyn in March as the pandemic hit to move back to his family in Texas. The 23-year-old data analyst for an educational nonprofit recently decided to return to New York and started searching for a new apartment on StreetEasy, spotting a one-bedroom apartment near Lincoln Center for $1,200 a month.

He and a roommate eventually settled on a two-bedroom apartment near the Parkside Avenue subway stop in Brooklyn for about the same $1,100 each a month they paid before — only with much more space, better views and a more convenient location.

“Because the rent is relatively low, it will be easy to sublease” if his or his roommate’s situation changes, Maymir noted.

Commuting Plans

After the pandemic ends, many real estate executives insist, the city’s economy will rebound, empty units will be filled and rents will move back to pre-pandemic levels. “When you are back in the office four to five days a week, you will want to be back in the city,” said Ariel Property Advisors President Shimon Shkury in the webinar where Gropper talked about his situation.

Miller and Wu are skeptical, saying the transition to working from home for many has raised the possibility that people will not return to the office full time. “Even after we have a vaccine, the ability of technology to lengthen the tether between work and home will allow longer commutes,” Miller said —especially if the commute is for two or three days a week and not five.

Wu independently used the same word — tether — to describe the likelihood people will choose suburbs if they don’t have to commute every weekday.

If Miller and Wu are right, the city’s system of rent regulation, which imposes price controls on about half the city’s units, could be endangered.

Every three years, the Census Bureau and the city’s Department of Housing Preservation conduct a study of the market to determine the vacancy rate, which must be 5% or less to justify a state of emergency and regulation. The next survey will be undertaken next year with the results available in 2022.

“It is relevant for housing advocates to think about the possibility that if flight from the city continues, there could be a question as to the need for rent regulation to continue,” said Sherwin Belkin, a lawyer specializing in rent law.

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.