Naseem Khan Alizai Keeps The Tradition Of Gold Jewelry Alive

LITTLE PAKISTAN – Naseem Khan Alizai for the last 28 years has spent his days selling gold jewelry on Coney Island Avenue. Some days, he closes his shop making zero bucks. Yet, every day (except on Fridays) he comes back.

Alizai, 50, owns the property located at 1064 Coney Island Avenue. His shop, Farrah Gold & Diamond is named after his first-born daughter and sits sandwiched between his two rivals – Meena Jewelers and Kangan Jewelers – as it has for almost two decades. He handpicks the jewelry sold at his store from six different countries around the world: Pakistan, India, Dubai, Bahrain, Singapore, and Turkey. But even with the variety, in a span of two hours, three customers came inside and left with nothing.

“It happens. Most people bought gold five years ago and when they come back, they expect it to be the same low price. That’s not true. The price of gold is always increasing,” Alizai said. “It’s a luxury item. People don’t need to buy it.”

But he keeps going.

Alizai came to America when he was just a teenager. He emigrated from Islamabad, Pakistan where he was the son of a family of landlords. He came for the same reason many other people immigrate to the country – for a better life. When he arrived in New York, he went straight to Manhattan. There, he visited Times Square, the Statue of Liberty, and the Brooklyn Bridge. Then, he spent one night and one day in Jackson Heights. He didn’t like it there very much and came over to Brooklyn. He’s been here ever since.

Soon enough, he opened a few businesses. One was Pak Bazaar, one of the three grocery shops in Little Pakistan back then. He also opened Pak Jewelers. He shut them both down after September 11, 2001.

“There was no business after 9/11 here. People were gone. There were no customers,” he said. “How can you survive? I used to have three women working for me. After 9/11, they all left. I was working for myself.”

A few years later, he opened Farrah’s Gold and Diamonds and he’s had it open ever since. The shop is located on a busy stretch of Little Pakistan. People pass by it every day, and though women may not always enter, they marvel at the jewelry from outside and whisper amongst themselves. To enter the shop, you must make eye contact with Alizai or his son working inside. They’ll buzz you in. Once you open the first door and are inside, someone will buzz you in again. The second door will open and you will be faced with two beautiful chandeliers and lots of gold. Gold bracelets, chains, small necklaces, rings, and earrings.

In 2015, Alizai got robbed at gunpoint. A woman customer had come in and asked to look at a necklace set. She was constantly texting somebody from her phone. Then, she had said her husband was outside the shop and wanted to come to see the jewelry. Alizai buzzed two men in and the lady left.

“They took my golds and bangles. I had a big loss, about a quarter to a million dollars,” he said. “And nobody helped me. I gave the police the video recording, everything. I don’t know why they didn’t help me.”

We asked Alizai multiple times if we could take photos of the beautiful gold. He smiled and shook his head no. Most of the jewelry are unique pieces, he said. People can easily take the picture and get it made elsewhere. A son and his mother came inside the shop. They were looking for gold rings, preferably with a blue emerald stone as a graduation gift. Alizai showed them a few designs. The customer, not meaning any harm, took a photo to show his sister. Alizai explained that he could not do that. Instead, the customer decided to Facetime and show the pieces live to the person across the line.

After 20 minutes, they left with nothing. They had tried to negotiate, but Alizai would not budge.

“This is not a grocery store or a clothing store in Pakistan where you can change the price,” he explained when they left. “It’s hard for people to understand that gold is very expensive and I need to make money.”

Making money the halal way is very important to Alizai. Part of the reason why he also shut down Pak Bazaar was that he was selling alcohol and lotto tickets. In Islam, both things are not allowed. But though the business isn’t necessarily booming now, he is still content with the shop he has built thus far.

“A human is never satisfied. If I have a million dollars today, tomorrow I’ll say I want two million,” he said. “It’s better to just trust in God.”

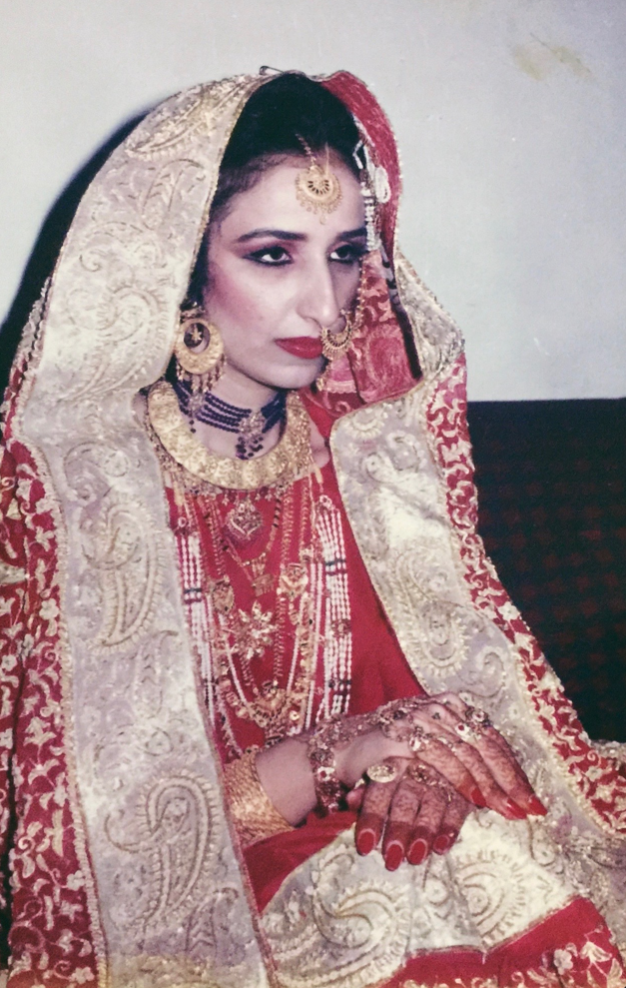

The bigger purchases are done by mothers and fathers, Alizai says – the heavier necklaces, earrings, and bangles – jewelry a South Asian bride would wear, according to custom and traditions that date back centuries. But now, even that is evolving.

“In our culture, during wedding times, you have to have a big necklace. We used to sell a lot of Iranian necklaces here. But, right now people cannot afford that anymore. It’s too heavy,” Alizai said. “Now, people like lighter stuff. When people cannot afford those kinds of stuff, it causes a little bit of change in tradition. But of course, if someone has money, they’d buy it.”

Though traditions are evolving, Alizai still has not gone fully online with his shop yet. He explained that he does have customers from about 15 states in the U.S. Some would choose designs from his Facebook page. Some would call him and ask him for bangle or necklace designs. He’d send them photos and videos, and they’d end up purchasing them. He’d deliver it to them with insurance.

“I even have customers in Canada. In Canada, jewelry stores are selling in very high prices,” he said. “Smart people call us to save money.”

Selling jewelry isn’t the only thing that keeps Alizai busy. The man also has his own organization, Alizai Foundation, where he provides charitable assistance to people in Pakistan. For example, he explained the concept of jahez, dowry. In Pakistan, it’s become common for the parents of the groom to demand a high dowry from the bride before marriage. The dowry can include a high sum of money, furniture, dishes, etc. If the bride’s family cannot give what is demanded, they won’t let their kids marry. In Islam, such a thing is not allowed. In Islam, only a mahr is required, where the groom gives what he can. Yet, Muslims in Pakistan do it anyway, Alizai explained.

“There are a lot of women in Pakistan who are poor. Most of them, their parents aren’t alive. And they’re not getting married because of jahez,” he said. “So, I help them. I buy them jahez.”

If he makes $100 in one day, about $25 to $30 will go to that fund. Every year, he helps about 15 to 20 women get married in Pakistan.

“Everyone has a right to live their lives, get married, and have a family,” he said. “When people, especially the boy’s mother, demand a lot of money, girls are just sitting there and getting old. So, I help them.”

The money he sends over takes care of furniture, clothing, dishes, and other necessities for the bride.

“When they start their new life, they won’t feel different,” he said. “They can say they had everything and the boy’s side of the family will not say anything to them.”

Alizai still plans on keeping and working in his business for years to come. When he is ready to retire, he plans to move back to the country he calls home.

“There’s no place like Pakistan,” he smiled. “When you have a wedding, the wedding lasts a month. When you die, every single day hundreds of people are coming over to your house to pray for you. And they don’t even know you. It’s just a beautiful culture.”

“In Pakistan, we have a rich culture. In Pakistan, there’s a family system, which I love. That’s not the same as in America,” he said. “I would like to say that everyone here is selfish. Everyone lives for themselves in America. Am I right or wrong?”

But retirement won’t come in a long time for Alizai. He’s still planning on standing inside his jewelry shop for about seven hours every day. Except on Fridays. He does not work on Fridays, he told a customer. Why? she asked.

“On Fridays, we work for Allah,” he smiled.