Mayoral Candidate Dianne Morales Water-Meter Bribe Probe Preceded 2004 Departure from Big City Schools Job

By Yoav Gonen and Greg B. Smith, THE CITY. This article was originally published on May 16 by THE CITY

Brooklyn Democratic primary contender lied to an investigator before acknowledging she directed her dad to pay $300 to make a $12,500 utility bill vanish, city records state.

Mayoral candidate Dianne Morales years ago participated in a $300 bribe of a city Department of Environmental Protection inspector who offered to make her $12,500 water bill go away, city investigative records obtained by THE CITY show.

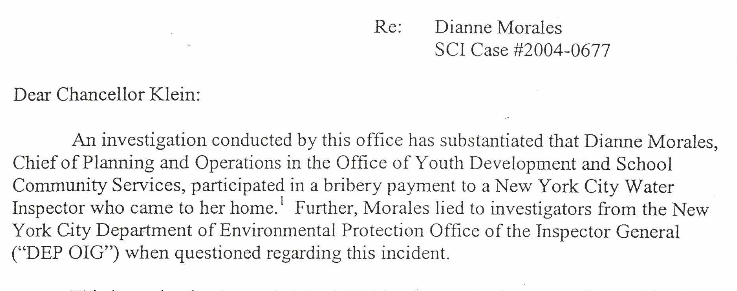

Morales was working as a senior employee at the city Department of Education when the probe concluded in June 2004. The DOE’s Special Commissioner of Investigation, which conducted the review, recommended in a letter to the schools chancellor summarizing the findings of the probe “that Morales’ employment with the DOE be terminated.”

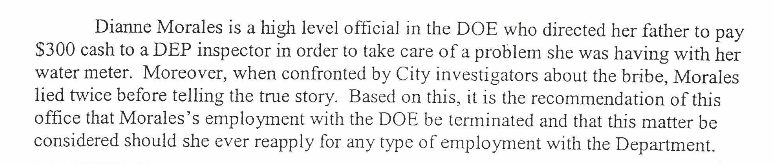

“Dianne Morales is a high level official in the DOE who directed her father to pay $300 cash to a DEP inspector in order to take care of a problem she was having with her water meter,” concluded the special commissioner, Richard Condon.

“Moreover, when confronted by city investigators about the bribe, Morales lied twice before telling the true story.”

She ultimately admitted to investigators that she had directed her father to pay the city water inspector $300 in cash on Oct. 23, 2002, the letter detailed.

According to a DOE spokesperson, Morales resigned from her post as chief of planning and operations in the Office of Youth Development and School Community Services in May 2004, before the findings were finalized.

Morales arranged for the payment after being pressed by a DEP inspector later prosecuted for targeting at least nine home and business owners for cash to make bills or fines go away. In six of those nine cases, the victims didn’t pay the bribes.

Her campaign spokesperson, Krysten Copeland, called Morales an “unfortunate victim.”

“Nearly two decades ago, Ms. Morales was a first-time New York homebuyer who received her first water bill for $12,552.15,” Copeland said in a statement. “Deeply concerned about the exorbitant amount, Ms. Morales requested an inspection through the appropriate city channels to determine the bill’s accuracy.”

She added: “Ms. Morales’s resignation from the DOE had nothing to do with the water bill situation and this is clearly an attempt by unscrupulous forces to draw conclusions where there are none.”

City Appointment Nixed

Morales, a former nonprofit executive who lives in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, is one of eight leading Democratic contenders for mayor, raising enough money to qualify for the official primary campaign debates that kicked off May 13.

Prior to her mayoral run, Morales had been poised to be appointed by Mayor Bill de Blasio and City Council as chair of the city’s Equal Employment Practices Commission, a little-known entity that acts as a watchdog over the diversity of hiring at city agencies.

She told THE CITY shortly ahead of the planned May 2019 appointment that she was raring to go.

“I have every intention of raising the profile of these topics and taking them head on,” she said at the time.

But the appointment never happened.

Weeks later, Morales told THE CITY she had withdrawn from contention for the position because she had decided to launch a new venture instead. In August 2019, she told The Bronx-based Norwood News that she planned to run for mayor, and the following year she made her bid to become the city’s first Afro-Latina mayor official.

But according to a former City Hall official, the appointment to the employment commission had fallen apart during the course of a standard background check.

The office of Mayor Bill de Blasio didn’t respond to questions about the background check, while a City Council spokesperson said the Council doesn’t comment on those types of reviews. DOI officials declined THE CITY’s request to release the background-check findings on Morales sent to the Mayor’s Office.

Asked whether the findings would have included the allegations of Morales lying about bribing the water inspector, a DOI spokesperson stated, “As part of its background investigation, DOI would share with a hiring agency any adverse information it was aware of regarding the person being backgrounded.”

A Progressive Run

Morales has gained a passionate following as the most boldly progressive major candidate in the running, vowing to cut the budget of the NYPD in half, promote worker cooperatives and create community-owned affordable housing.

A recent PoliticoNY analysis showed Morales with the third-highest number of contributors and the smallest average donation, at $74 — a marker of strong, grassroots support.

After working as the CEO of the antipoverty nonprofit Phipps Neighborhoods for 10 years, Morales stepped down in early 2020 to run for mayor. She formally announced her candidacy on Nov. 19.

She was recently co-endorsed by the progressive Working Families Party, along with former mayoral counsel Maya Wiley.

WFP had initially endorsed Scott Stringer as its top pick in ranked-choice voting, followed by Morales and Wiley. But the party withdrew its Stringer nod following sexual misconduct allegations that the comptroller has denied.

Morales, 53, has struggled to make headway in recent polls. The latest, by Schoen Cooperman Research, placed her eighth among the top candidates, at 4%.

Different Versions of Account

At the time of the reported 2002 incident, Morales was employed by the nonprofit New Visions for Public Schools under a DOE contract, the letter to the schools chancellor indicates. Property records show she had recently purchased the multi-unit home where she still lives.

Morales was first interviewed by a Department of Investigation official by phone in March 2003, after the agency had received complaints from a number of homeowners about a water inspector seeking bribes, according to DOI and SCI documents.

In her first version of the story, Morales said she made an appointment with the water inspector after receiving a $12,000 bill — but that it was her father who had handled the entire affair because she “did not know the first thing about meters or mechanical things,” according to Condon’s letter to then-Schools Chancellor Joel Klein.

Morales recounted that the inspector told her father that the family had to hire someone to install a water meter, they were facing a fine, and they would have to settle the entire $12,000 bill. The worker then offered to install the meter and take care of the outstanding bill if they paid him between $150 and $300, the SCI report says.

Morales told the DOI investigator she couldn’t remember the exact amount.

The inspector installed the meter, her father paid him $300 in cash, and the $12,000 charge was removed from the subsequent water bill, Morales told the investigator.

Four days later, however, she “gave an entirely different version of events,” according to the SCI report.

This time, she said she personally dealt with the water inspector, who explained the same set of issues with the lack of a meter, the outstanding water bill and the need to levy a fine, the report said. The worker said something about how he “could take care of it” for her and “they could work it out.”

Morales says he told her he could install the meter for $300 in cash, which she understood would also eliminate the fine and the outstanding water bill — which in this telling was $11,000, according to the report.

The SCI report notes the water bill was $12,552.15.

Morales said in this second account that she paid the water inspector $300 in $10 and $20 bills, that he provided no paperwork and that the outstanding water tab was eliminated from the next bill, according to the SCI report.

In a third interview with the DOI investigator, Morales said her father had been at home and she had been at work when the water inspector showed up, and that she had communicated with both of them by phone.

This time, she said it was her father who relayed to her the inspector’s offer to “take care of this for $300” — and that her father paid the man with three $100 bills, the SCI report found.

When Morales was later interviewed under oath by SCI, with her attorney present, she acknowledged lying to the DOI investigator — though she maintained she had told only one false version of events, in order to protect her father — and affirmed that the latest version of the story was the truth, according to the SCI report.

(The report noted that investigators talked to Morales’ father and that he’d confirmed he was at her house and dealt with the inspector.)

Morales said she asked her father to pay the inspector the $300 with the understanding that the cash would correct the bill, waive the fine, and have a meter installed, the SCI report says.

Morales summarized her actions as “responding to a city official’s order basically to do what [she] needed to do in order to bring [her] account and [her] status up to par,” according to the SCI report.

Wider Net

Morales wasn’t alone among home and business owners hit up for payments by the same DEP water inspector.

In December 2002, a Brooklyn couple contacted DEP officials to complain that veteran inspector Herbie Barnwell had asked them for $500 in cash to install a meter and to skip issuing them a notice of violation.

That investigation found that between October 2001 and December 2002, Barnwell had solicited $3,350 in bribes from nine home or business owners in a similar manner. Six rejected paying bribes, while three others ponied up a total of $600 in payoffs, according to the DOI memo.

Morales’ campaign said Barnwell is the water inspector who came to her home in October 2002.

“Ms. Morales, as an unfortunate victim of Mr. Barnwell’s actions, has made several attempts throughout the years to seek official resolution through the appropriate city channels but was repeatedly told there were no findings or outstanding claims about her or her property,” said Copeland.

In 2003, DOI referred the case to the Brooklyn District Attorney’s Rackets Bureau and Barnwell was charged with multiple counts of bribe-receiving, attempted grand larceny and official misconduct targeting four customers, according to a criminal complaint.

Three of the four customers cited in the case brought by the Brooklyn DA’s Office refused his demand for bribes; the fourth coughed up $200 cash.

Court records obtained by THE CITY show Morales’ case is not part of the complaint.

One victim in the case against Barnwell said the inspector threatened to impose a $2,500 fine for what he deemed to be a meter in violation of DEP rules. When Barnwell said he could make the fine “go away” for $1,250 cash, the victim refused and the inspector issued him a $250 fine, according to the complaint.

A second victim was washing a customer’s car outside his auto body shop when Barnwell accused him of violating the city’s drought regulations. The victim refused his demand for a $100 cash bribe and got hit with a $250 fine for “using public water to wash vehicles.”

The victim who paid a bribe told DOI that Barnwell installed a new meter in his building and dropped his threat to issue violations.

Barnwell went to trial and was convicted of official misconduct in April 2006. He was later sentenced to three years probation and died in 2017.

Copeland, the campaign spokesperson, said the experience left a lasting impression on Morales.

“Ms. Morales’s commitment to ensuring that other mothers, families, and vulnerable communities are not subjected to similar incidents, especially the many Black homeowners and seniors in Brooklyn who are often targeted by such schemes, is based on her personal experience with predatory practices, abuses of power and bureaucracies that do not serve all communities equally,” Copeland said.

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.