Fight For Ownership In ‘Little Pakistan’ Continues — This Time Over A Beloved Mosque

MIDWOOD – An ivory colored structure stands sandwiched between two typical brick-colored three-story buildings between Avenue H and Glenwood Road on Coney Island Avenue. Though the stores next to it have closed and new ones have opened, Makki Masjid has stayed in that very spot since 1982.

The Mosque, whose official name is the Muslim Community Center of Brooklyn, has served as a place of refuge for Pakistani immigrants for decades. At every Jummah prayer, there are at least 3,000 congregants; there are even more during Eid and Taraweeh prayers. Makki Masjid is a place where many neighbors have grieved the death of their loved ones. It’s a place for activism. After 9/11, it stood as a reminder of hope. If the Statue of Liberty is a symbol of America, Makki Masjid holds the torch for Little Pakistan.

But now, everything is changing. People are fighting — literally. For what? A big ego? Money? A clash between nationalities? Transfer of power?

How about, all of the above?

Last Friday, Nov. 2, 66-year-old Akram Amin Khan, the president of the Mosque, was arrested outside the building. The NYPD tells Bklyner he was charged with assault after a victim claimed Amin Khan grabbed him by the shirt and punched him on the face numerous times, causing pain and swelling. Cops say the victim refused medical attention at the scene.

Every Friday, money is collected from the congregants for donation. Phrases like “But you aren’t doing anything for the masjid,” and “This is a masjid, why are you fighting?” can be heard in the video of a fight that happened one week before the arrest. “Why don’t you hold an election?” someone shouts. The argument gets physical.

“He shouldn’t have called the police,” Shahid Khan, founder of the non-profit, National Youth Organization of Pakistan said.

Shahid Khan is a community organizer and a very passionate one at that. He spoke over the phone; his tongue slipping from English to Urdu. He must have realized many jokes weren’t as funny in English, so he stuck with his native language.

“Zainab! Bring your mom’s big chappal and come down to Coney Island Avenue,” he laughed, referring to shoes that brown moms use to scold their children. “That is the only solution!”

“Where do I begin?” he sighed. There are a lot of factors contributing to fights at the Mosque. According to Shahid Khan, there’s a gap between the newcomers and ones who’ve been here a long time. “The old ones, they have a big ego, are conservative, and have complicated thoughts,” he said. “Many of the new ones are educated, were born here, can compromise, but they don’t have anything.”

It turns out the “newcomers” have had enough. They argue that the Mosque isn’t being run the right away. Where is the money going, they say?

Shahid Khan estimates that in one Jummah, people donate a total of $3,000 – $4,000. The money is supposed to be used on the Mosque; at least, that is why people donate. But that is not what it is being entirely used for.

It seems like the Mosque has always been under construction. Living in the neighborhood since one was born, it could be seen that scaffolding was routinely put up and donations boxes were always placed inside stores asking for money to “fix and build the Mosque.” But somehow after tremendous amounts of money, there is still scaffolding outside the Mosque (this time to build a pillar). And in a structure with over 3,000 congregants praying during the hot nights of Ramadan, there are still no air conditioners. So where does the money go?

“This is a big mafia,” Shahid Khan claimed. “Their intention isn’t good. Think about it, if the masjid is entirely built, who will give donations? Where will these people get the money to do their businesses? How will they get the money to use on the multiple gas stations that they own?”

Another contributor to the downfall of the Mosque is family. The old ones and the newcomers are all, one way or another, related to one another. “This masjid is a family enterprise,” Shahid Khan said.

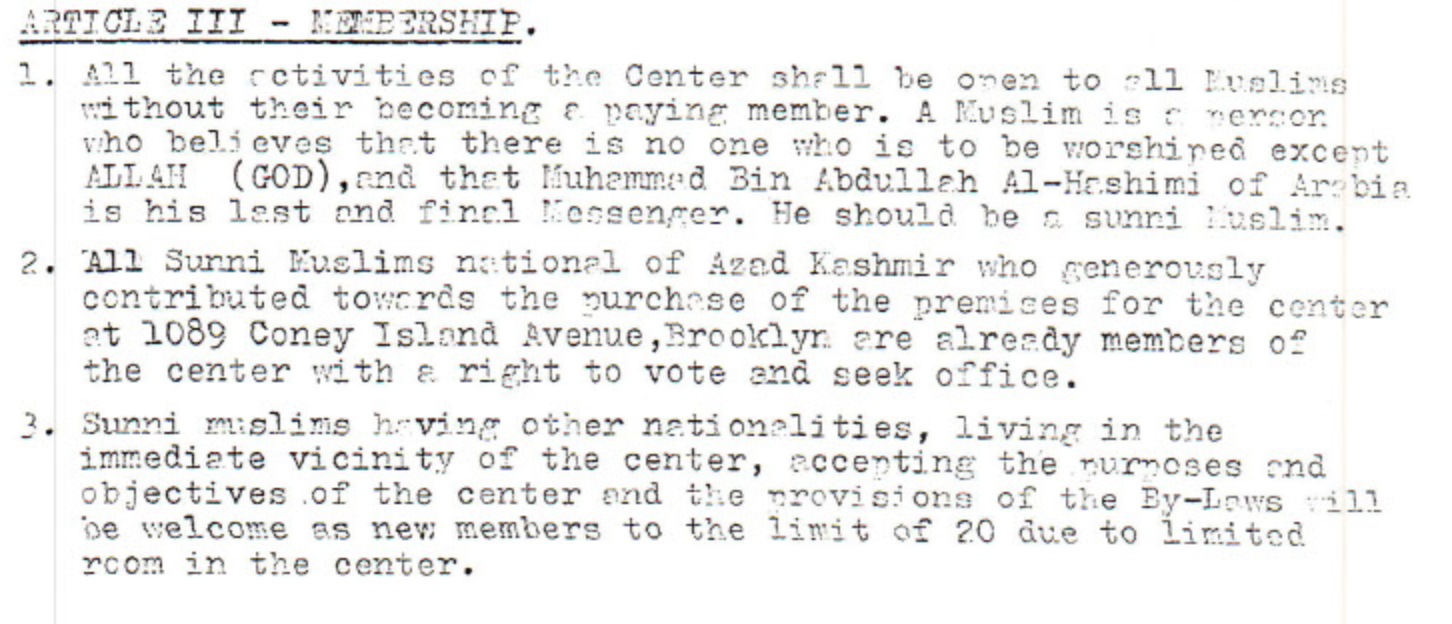

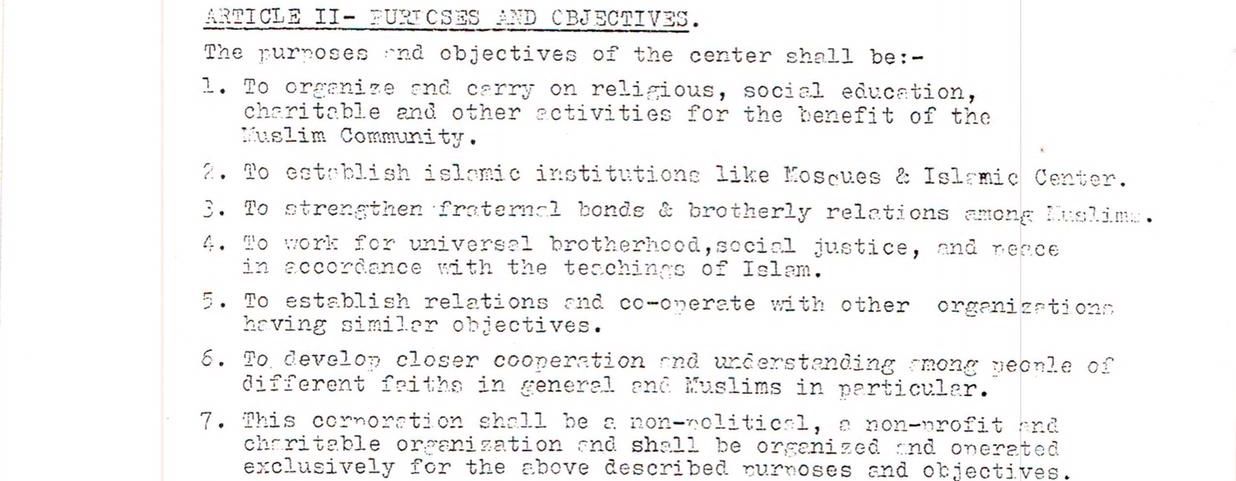

The majority of the families are from Azad Kashmir. They are referred to as Mirpuri (which comes from the word Mirpur, which is the largest city in Azad Kashmir). According to the Makki Masjid constitution, all members of the Mosque must be Mirpuri (because it was indeed Mirpuri who founded the Mosque in the first place). In a neighborhood where many are Punjabi (people from Lahore, Pakistan) and Sindhi (people from Karachi, Pakistan), conflict is sure to erupt.

The Mosque’s constitution can be viewed here.

“There’s a big fight between the Kashmiri and the Punjabi,” Shahid Khan said. “The Punjabi say ‘we’re donating the most money to the masjid, so why don’t we get a say?'”

It makes sense that members of the Mosque want to obey the constitution’s policy requiring only those from Azad Kashmir to be members, but many argue that other parts of the constitution should also be obeyed.

Article II states, “The purpose and objectives of the center shall be: – to strengthen fraternal bonds and brotherly relations among Muslims.”

What about #4.: “The purpose and objectives of the center shall be: – to work for universal brotherhood, social justice, and peace in accordance with the teachings of Islam?”

Or #6: “The purpose and objectives of the center shall be: – to develop closer cooperation and understanding among people of different faiths in general and Muslims in particular?”

The recent fights over ownership at the Mosque prove otherwise. It’s counteractive to say only Mirpuri have the biggest say in the Mosque, and then also use words like “brotherhood,” “fraternal bonds,” “understanding,” “cooperation,” and “peace.” According to Shahid Khan, many people are arguing simply for a say and they are not getting it because the constitution is quoted back at them. But what about Article II?

The cancelation of the Independence Day mela also played a big role in this mosque situation. The mela had occurred at the same time and place for 17 years until disputes among community members got it canceled. Similarly to the Makki Masjid situation, the dispute began with a “Why should the other group continue to be the organizers?”

“The community was already frustrated and depressed after the cancelation of the mela,” Shahid Khan said. “Many of the people involved in the mela situation are a part of Makki Masjid.”

According to Shahid Khan, if anybody has a problem with how something is being run, they should list all the points and bring it up legally. You can’t just go to someone and tell them to give you the mosque, no matter how good your argument might be, he said.

“If I go home and my wife tells me to leave and says I can’t stay there anymore, how does that make sense?” he asked. “At least tell me what I did and allow me to say something.”

“There needs to be a procedure, which this community does not seem to have.”

Shahid Khan believes the community is all alone. He says the council member doesn’t do anything, nor does anyone else in power. “So, I tell people to vote in the elections if they want to see things fixed. But nobody votes!”

“We call it Little Pakistan and we act like we’re the biggest and baddest and we can do anything, but we don’t vote. Who’s going to listen to us if we don’t vote?”

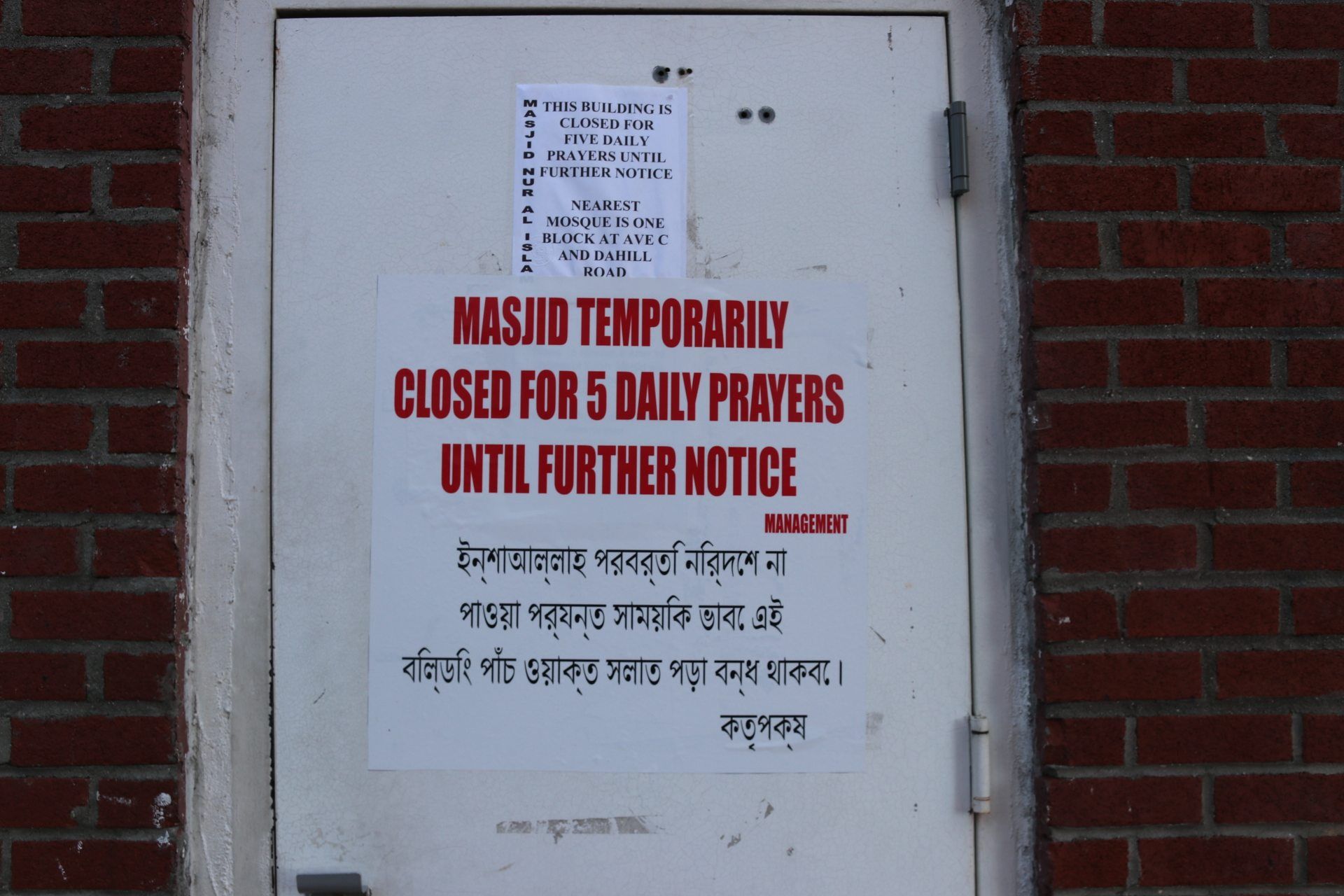

Shahid Khan is afraid the Mosque might shut down. And if it does, it won’t be the first time a Mosque would have locked its doors in Brooklyn. In August, an imam at a mosque in Kensington resigned and locked all of the doors after claims of embezzlement.

But until anything happens, the ivory-colored structure will remain standing, squished in between two typical brick-colored buildings. And despite what goes down, both groups of people genuinely love Makki Masjid and want what they think is best for it.

“These fights have ruined our community,” Shahid Khan said. “Things have gotten so bad, I don’t see them getting better any time soon.”

We reached out to the owner of the mosque, Ali Mushtaq, but he did not get back to for comment. Balal Khan and Amin Khan were unavailable for comment.