Local Cooking Class Feels Like Spending a Day in Grandma’s Kitchen

When I first moved to Kensington, I was overwhelmed by the array of Indian/Pakistani/Bangladeshi groceries on Church ave and McDonald. After gaping at the racks of neon spices (mango powder? Kalonji?), I’d leave the store empty handed.

That’s why I was thrilled to find League of Kitchens, a culinary school with a local twist: hands-on classes taught by immigrants in their own kitchens.

My boyfriend Jon and I chose Afsari’s Bengali Ramadan Workshop in Bay Ridge; we were eager to match the rising curry smells from our downstairs neighbors.

Afsari, the Bengali teacher, welcomed us (five students from Brooklyn and Queens) into her home with small bowls of chole muri (red chickpeas with crispy rice), chana dahl (chickpea lentil, cilantro, fresh ginger, and lime juice), sweet dates, sweet jalebi, and a pitcher of spiced ginger tea.

“We [at League of Kitchens] design the menu so everything goes together; the mains, sides, and breads complement each other,” Afsari said as she handed us recipes of the meal we were about to cook. But as the day progressed, I realized there was way more to this Southeast Asian cuisine than what’s on the page.

While we ate lunch, she introduced us to her history and the importance of the Ramadan meal. “When I first moved to Bay Ridge in 2000, Ramadan was on Thanksgiving,” she told us.

Muslims observing Ramadan, the holiest month of the Islamic calendar, fast between dawn and sunset, so the break-fast meals (the suhoor served before dawn and the iftar served after sunset) are especially nutrient dense. Bangladesh is 95 percent Muslim, according to Afsari, so the Ramadan meal is a cornerstone of their culture.

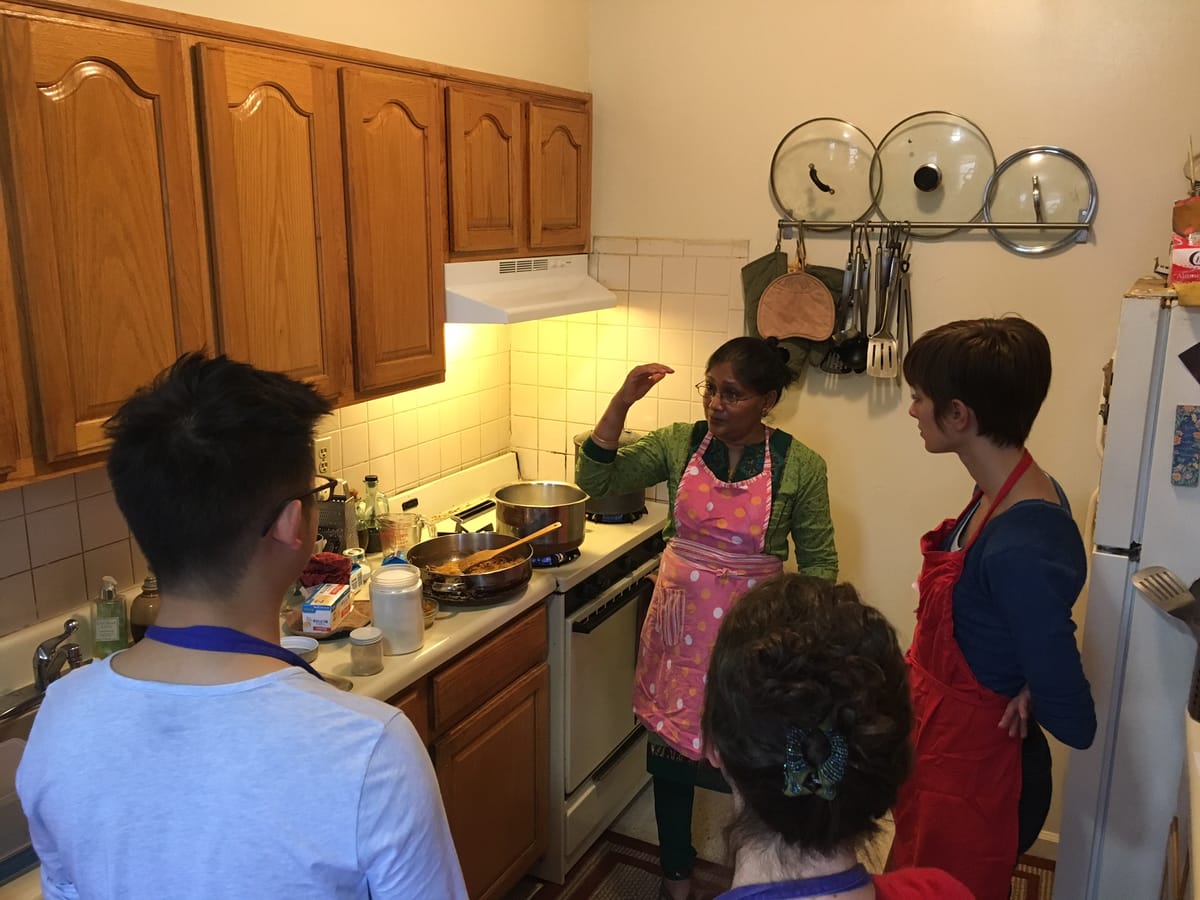

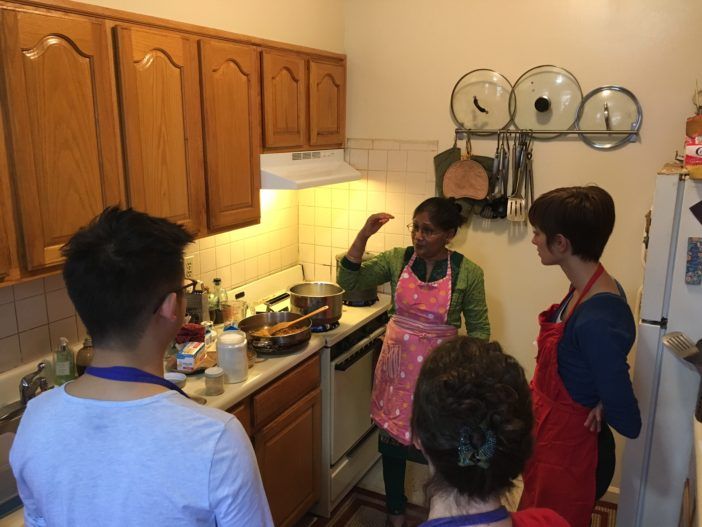

After lunch, we don our aprons and crowd around Afsari’s tiny stove.

For the next 3 hours, she works like an orchestra conductor, guiding us intuitively through each step of beef with yogurt sauce, aromatic rice, vermicelli pudding, and multiple sauces, peppering in tips like how to keep caramelized onions crispy and draw the best flavor out of green chili peppers, while thickening the pot with stories and commentary.

Even rice is a multi-layered culinary experience. “In our culture, if you make a good rice you are a good cook,” she said while throwing whole spices into the pot of rice and poking holes in the top layer to retain moisture during baking.

Over the years, Afsari mastered her own cooking technique by blending together her mother’s traditions with local ingredients, cook books—and plenty of trial and error. And sometimes, she still calls her mom for help.

Afsari’s mother enforces strict rules about how to cut an onion, and now after running her own kitchen Afsari finally understands why. “Each way you cut the onion will produce a different flavor for your dish,” she told us.

Spices and herbs are an essential ingredient in Bangladeshi cuisine, including bay leaf, cilantro, and mango powder. Asfari pulls jars of powdered and whole spices from every corner of her kitchen. “The heat from Indian food comes from these spices, not just from the chili,” she said, “and each spice brings health benefits, not just flavor.”

One of Afsari’s many secrets is her homemade spices. “I always make garam masala and fennel powder myself, never store bought.”

As we start the Pakora, I try to follow the recipe sheet as Afsari fills the bowl with chickpea flour, cilantro, shredded vegetables, sliced onions, whole cumin seed, fennel seed, and black onion seeds. But she reminds us, “Each and every dish is my experience, not just what’s in the recipe.” She practices sensory cooking, that is, using taste, smell, sight, feel, and memory—rather than following exact numbers.

In Afsari’s kitchen, cooking is always a hands-on experience. Always use your hands to mix, never a spoon or spatula, “If someone tells you ‘I never use my hands in cooking’, that is the biggest lie” she said as she dug her fingers into the bowl.

Since League of Kitchens was featured on the Colbert Show in early January, her workshops usually sell out months in advance. And it’s easy to see why—Asfari is a patient cook and engaging storyteller, who teaches both beginners and professional chefs.

When we finally sat down to dinner, there were so many bowls on the table there was barely any room for our plates. Yogurt beef tehari with fragrant kalijira rice, pakoras with mint dipping sauce, chapati bread, raita, halim, and of course Semai (Vermicelli pudding) and a beautiful fruit plate for dessert.

We left Afsari’s apartment with full bellies, leftovers, and hand-typed recipes crammed with notes. But even more valuable, Jon and I came home with a deeper understanding of our own neighborhood, not to mention how to navigate those Church avenue grocery stores.League of Kitchens offers a variety of classes in Bay Ridge, Borough Park, Queens and Manhattan, cuisines including Bangladeshi, Japanese, Uzbek, Lebanese, Trinidadian, Argentinan, Indian, and Greek. Check out their classes here