JFK Assassination Remains A Defining Moment For Baby Boomers

BETWEEN THE LINES: The following is an excerpt from one of several speeches that Senator John F. Kennedy made in Brooklyn, on October 20, 1960:

I come over here to Brooklyn to ask your help. I run for the Presidency in the most difficult time in the life of our country, but with the greatest confidence, that if this country is given the kind of leadership which I believe it needs, if we are willing to go to work again, this country can meet any obstacle and can serve as an inspiration to freedom around the globe. So I come to Brooklyn to ask your help in this campaign, and if we are elected, we are going to go to work.

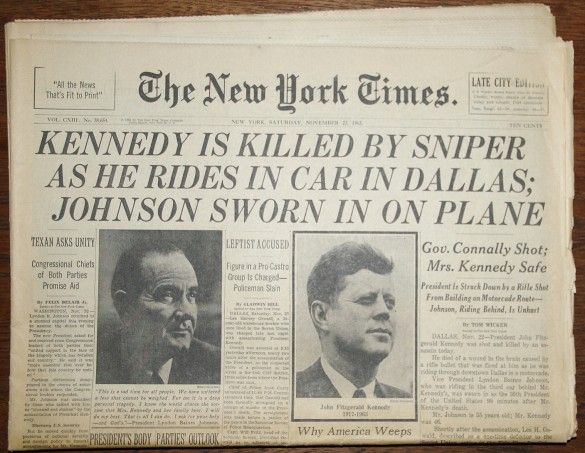

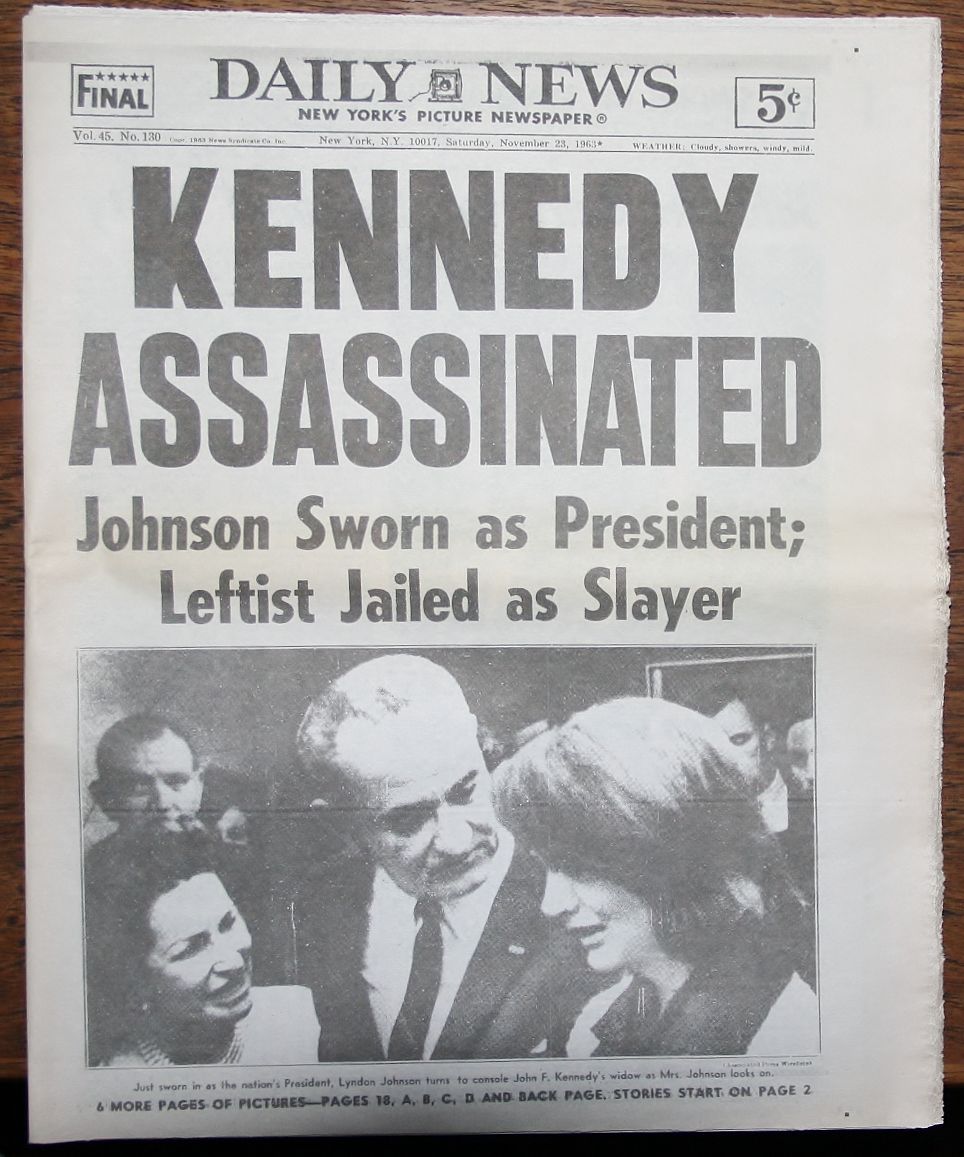

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, one of the most alarming signposts in American history and a defining moment that echoes for many Americans over the age of 40, especially the post-World War II generation.

Between December 7, 1941 and September 11, 2001, no episode so deeply affected America’s shared consciousness as JFK’s assassination. For the first wave of baby boomers — including yours truly — who were teenagers at the time, the death of the nation’s 35th president remains a haunting recollection. In a few short years, Kennedy motivated our budding, politically naive generation, which represented the largest demographic shift in US history.

The bullets fired on November 22, 1963, not only altered American history, but shattered the post-World War II / Korean War period of peace and prosperity. Moreover, that incident was the prelude to a progressing, turbulent decade marred by protests, riots, a controversial conflict, and assassinations of other respected leaders.

After reports of the assassination jolted the nation, a period of shock and mourning set in and remains as fresh as that Friday afternoon when a bulletin interrupted the program I was watching. The lunchtime report was soon followed by the most dreaded news possible: “President Kennedy is dead.” That breaking news from Dallas, due to the era’s limited technology, was delayed to the East Coast by nearly 30 minutes.

From the instant when correspondents Walter Cronkite on CBS and Robert McNeil on NBC relayed the awful news, and for the next three, numbing days, my family, and, indeed, most of the nation and world, sat glued to televisions and radios anxiously waiting for any bits of information about the tragedy’s unfolding aftermath.

Some moments and images from that somber weekend continue to stand out: Jack Ruby lunging, shooting prime suspect Lee Harvey Oswald point blank; thousands passing the coffin lying in state under the Capitol rotunda; the precise, painstaking funeral procession moving oddly silent, aside from the synchronized clip-clop of six white horses pulling the flag-draped coffin and the muffled drumbeats, through the ordinarily congested streets of the nation’s Capital; the isolated riderless black horse; an impeccably poised Jacqueline Kennedy holding her young children’s hands; and the poignant image of John-John saluting his father’s casket as it passed by on his third birthday (and my 17th).

My singular Kennedy experience was when the senator, after winning the Democratic nomination, campaigned in Brooklyn, in the summer of 1960, for New York’s 45 electoral votes. My friend Larry and I went to the rally along Kings Highway that stretched from Ocean Avenue to Coney Island Avenue, and onto several side streets, and waited hours among the jam-packed crowd. As we stood at the East 16th Street intersection, opposite Dubrow’s cafeteria, we were constantly pushed and shoved by others impatiently awaiting the candidate’s motorcade.

As the police escort cleared a path, the presidential limousine convertible with Kennedy, headed east on Kings Highway, got closer when it passed under the elevated subway platform. That is when we saw him. I remember his full head of reddish hair and engaging smile. Larry and I tried to inch forward, but we never got nearer than 50 feet or so. We wanted to be one of the lucky ones to shake his hand, but were impeded by the crunch of supporters in front of us. The entourage stopped, JFK made a few remarks, but, in minutes, the car moved towards Ocean Avenue.

Though it was nothing more than a brief glimpse, Larry and I were, nonetheless, thrilled and felt we’d gotten as close as possible to the man who might be the next president. In the frenzied crowd dispersal, Larry lost a shoe and my shirtsleeve was torn. Minor damage for an incomparable experience.

Last week, in one of our periodic get-togethers, Larry and I, along with Steve, another lifelong friend, and their wives, Lynne and Sharon, went to see the detailed Newseum exhibit, in Washington, DC, which chronicles John F. Kennedy’s presidency, family life and death.

The exhibition convincingly attests that the four days of around-the-clock coverage of the assassination and funeral accelerated television as the primary source of current events — until the advent of 24/7 cable news and the immediacy of the internet decades later.

The emerging electronic medium had already influenced the 1960 campaign and election. Kennedy effectively used television to project an image of vitality and appeal that was sorely lacking in Dwight Eisenhower, the older president he was trying to succeed, as well as his discernible comfort on camera. That was more than evident during the first ever televised presidential debate as Kennedy seemed confident and composed, while his GOP opponent, Vice President Richard M. Nixon, visibly perspired under the hot stage lights and was perceived as edgy and tense. That difference undeniably attributed to Kennedy’s narrow victory, one of the closest in presidential election history.

Subsequent blemishes on the Kennedy legacy regarding womanizing, extramarital indulgences and ties to organized crime that surfaced after his death, notwithstanding, cannot erase Kennedy’s achievements, such as creating the Peace Corps, advancing the space program, marshaling federal troops at the University of Mississippi that helped facilitate equality for black Americans, and facing up to the Russian Premier Nikita Khrushchev in a nuclear confrontation that sidestepped devastating global consequences.

While the portion of his inaugural address on foreign policy depicted the new president as a Cold War advocate, Kennedy’s position had changed several months before his death, when he said, “…our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future…”

Despite holding office for a mere thousand days — too fleeting to sufficiently evaluate a presidency — the sense of hope and anticipation that John F. Kennedy instilled in many who were too young to vote for him is immeasurable. Consequently, Baby Boomers willingly accepted the symbolic torch he passed to a generation preparing to face a changing world. In the ensuing turbulent decade, as they matured, the nation was plagued by protests, riots, a divisive conflict and more assassinations of popular leaders.

The tragedy of Kennedy’s unfinished life has had a lasting effect on the way he is remembered. Traditionally, we commemorate distinguished historical figures such as President Abraham Lincoln, President George Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on their birthdays, but, when it comes to our 35th president, his death, not his birth, is observed.

The bullets fired half a century ago altered American history, and also cut short the promising optimism ever fulfilled, but also helped exaggerate the mystique about the fallen president.

Nevertheless, like the eternal flame at his Arlington National Cemetery grave, JFK kindled a spark in a naïve, nascent generation that represented the largest demographic shift in American history.

In the final analysis, John F. Kennedy’s characteristic vigor and public charisma were beacons that not only induced our initial political encounter, but motivated a consciousness that impacted our lives and, more significantly, our social perspectives.

Neil S. Friedman is a veteran reporter and photographer, and spent 15 years as an editor for a Brooklyn weekly newspaper. He also did public relations work for Showtime, The Rolling Stones and Michael Jackson. Friedman contributes a weekly column called “Between the Lines” on life, culture and politics in Sheepshead Bay.

Disclaimer: The above is an opinion column and may not represent the thoughts or position of Sheepshead Bites. Based upon their expertise in their respective fields, our columnists are responsible for fact-checking their own work, and their submissions are edited only for length, grammar and clarity. If you would like to submit an opinion piece or become a regularly featured contributor, please e-mail nberke [at] sheepsheadbites [dot] com.