JFK Airport Plan To Discharge Toxic Chemicals Into Jamaica Bay Sparks Backlash From Environmentalists

A proposal to allow deicing chemicals and other toxins from John F. Kennedy International Airport to flow freely into Jamaica Bay has sparked a heated debate between city and state agencies and local stakeholders around New York City’s most important federal parkland.

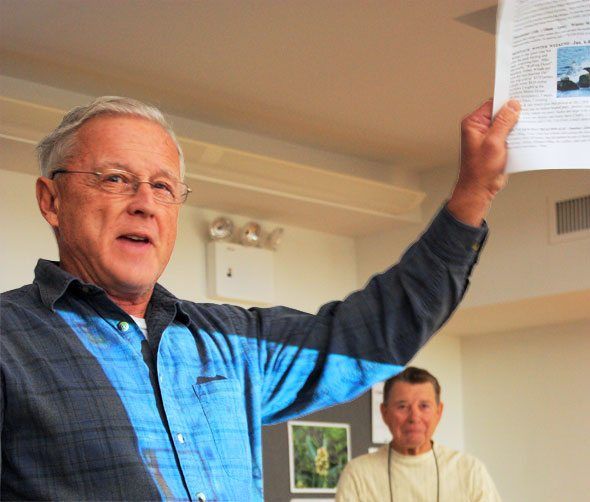

The arguments unfolded at a packed meeting on Thursday of the Jamaica Bay Task Force, an advisory committee made up of government agencies, activists, scientists and community members concerned about the preservation and revitalization of Jamaica Bay.

The meeting centered on updates of the three major points:

- A report on the progression of several pilot programs instated by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection to reintroduce indigenous species of oysters, eelgrass and algae into the bay;

- A discussion led by the by the ACOE on the developments of the three marshland restoration efforts – Gerritsen Creek being the most recent;

- The modification of the Port Authority State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permits (SPDES), which authorizes the discharge of deicing chemicals and other toxins into Jamaica Bay from JFK airport.

Concerned residents filled the room at the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center, with many standing for the duration of the two-hour meeting. The task force includes agencies and watchdog groups such as the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, New York City Department of Environmental Protection, US Army Corps of Engineers, New York City Audubon Society, Jamaica Bay Ecowatchers, American Littoral Society, and National Park Service.

According to environmental watchdogs at the meeting, runoff of water and chemicals from JFK airport remains a major contributor of pollution to Jamaica Bay, and modifying current permits could make matters worse.

“We really need more information about the type of toxins coming into the Bay, what levels are coming in, and what the impacts are of those particular chemicals,” Don Riepe, director of the Northeast Chapter of the American Littoral Society and Jamaica Bay Guardian, told Sheepshead Bites. “We understand the need for deicing planes, but we need a better way of capturing it, and we need to know more … before permits are given carte blanche.”

Currently, there are 26 large pipes that discharge untreated waste from JFK into various locations in the bay. The consequences are devastating, and, until recent restoration efforts, water was not able to sustain local marine life and marshlands were receding at about 33 acres annually.

“More has to be done. Time is of the essence. These marshes are eroding at a fairly rapid rate and we need to ratchet up [preservation efforts],” Riepe said.

Region 2 Director of the DEC Venetia Lannon discussed the permits, along with Environmental Engineer Sebastian Zacharias, and Jean Occidental, an environmental engineer working with the industrial permit section.

The DEC representatives outlined the plan, adding that they have already curtailed the dumping of ethylene glycol, a type of antifreeze.

But those improvements haven’t been enough, said Riepe. He said testing done by the Ecowatchers still showed toxic materials in the waters.

“We’re looking into the comments made by your organizations and going through the paperwork,” Occidental replied to his concerns.

The issue will be revisited soon, as the DEC has not yet come to a conclusion on the permits.

Also at the meeting, DEP’s John McLaughlin spoke about several specific projects, including efforts to root thousands of eelgrass shoots at various test sites and monitor the growth. Two of the sites are directly east and west of Kingsborough Community College.

The issue of replanted eelgrass goes deeper for McLaughlin, as these tests will determine whether or not the water quality in Jamaica Bay has improved to sustain the kind of flora and fauna that once populated the waters, but died out or left as water quality and climate changed.

“The eelgrass actually improves the quality of the water because it acts like a filter for nitrogen. It’s return is vital for the Bay,” said a Parks official who has been following the project since 2009.

Though some areas have benefited from the project, there are several sites where the eelgrass has not grown. McLaughlin is still optimistic because data shows that natural factors – and not pollution – may be hindering the plants from taking root.

“Mud snails get on the leaves, predation and sand wave movement [are impacting the project],” said McLaughlin.

McLaughin said his team will scale all of their recuperative efforts up.

As for the marshlands, they too have been doing well, reported Lenny Houston of the Army Corps of Engineers. The 37 acres of marshes in Gerritsen Creek are nearly complete, and nature trails are scheduled to reopen next year after a long effort was made to improve water quality, rebuild tidal channels that were previously filled, and restore acres of marshland.

“I’ve never seen salt marshes grow better,” said Houston.

The same can’t yet be said for Plumb Beach. Houston said that the case for Plumb Beach’s restoration has been made, but the project and the funds are still tied up with lawyers and government bodies. Still, the Army Corp of Engineers plans to push forward with the project.

“We made the case for Yellow Bar, and hope to make the case for Plumb beach,” added Houston.

— Laura Vladimirova