How To Save Everyone: Doc who Saved Hundreds After Las Vegas Mass Shooting Trains Colleagues in Brooklyn

FLATBUSH — On the night of the mass shooting at the Las Vegas Harvest Festival in Las Vegas that killed 58 people and wounded several hundred, Dr. Kevin Menes was on duty at nearby Sunrise Hospital. There, Dr. Menes, a night shift physician, and his colleagues were responsible for saving roughly 200 gunshot victims after they arrived at the hospital.

“I just happened to be scheduled that night,” Menes, 41, told Bklyner Wednesday.

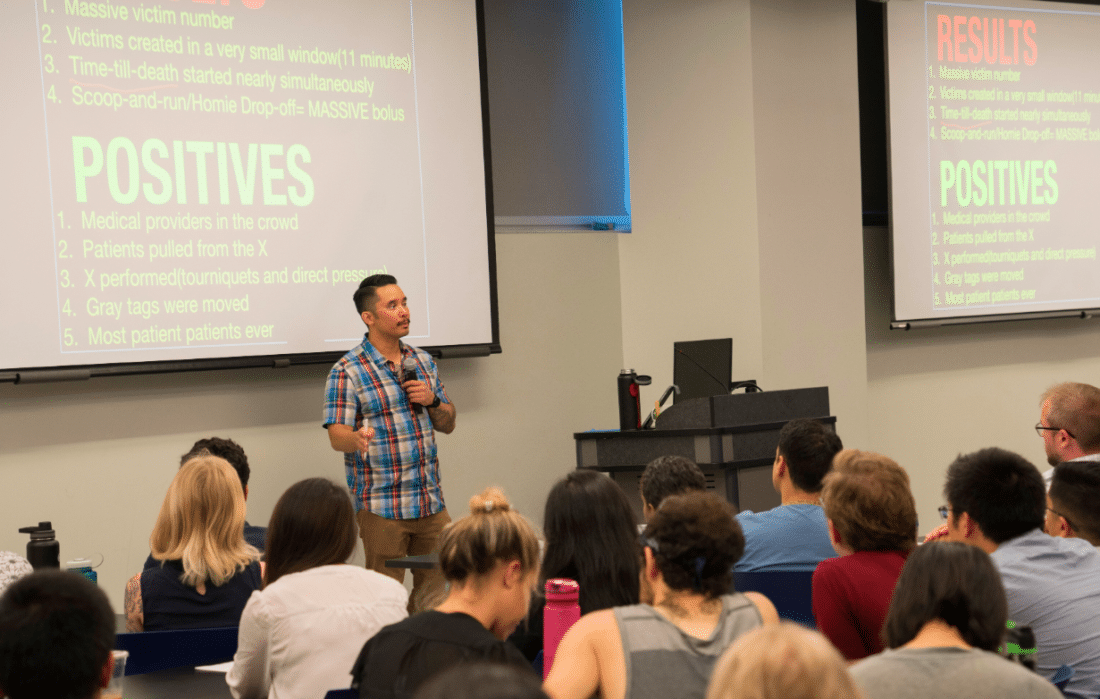

On Wednesday, Menes came to SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Flatbush to impart the knowledge he learned on that night two years ago to emergency medicine residents. SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, notably, is the lead institution in a 17-member coalition responsible for coordinating mass casualty emergency preparedness in Brooklyn, making it all the more important its residents receive training on the matter.

“We didn’t teach this, this was not a standard part of our core curriculum, but more recently, it’s being written about, people are lecturing on it, people are having to prepare for these mass-casualty incidents,” Dr. Teresa Smith, director of the Emergency Medicine Residency Program at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, said in an interview following the Dr. Menes’ teaching session.

“Whether it be natural disasters, whether it be mass shootings, it’s not about if it’s going to happen to you, but when it is … so we are preparing physicians for what can potentially happen.”

Wednesday’s conference, hospital officials said, was attended by about 40 residents and 40 other medical students. What did they learn from Menes?

Dr. Menes explained that, as of now, “there is very little written out what to do” in the emergency room in the aftermath of a mass shooting. He taught residents Wednesday morning “the mechanical portions of what would be expected … if a large mass casualty ended up coming to your hospital.”

“I’m trying to take the knowledge that I had from that night and try to share it to these doctors, so if they’re ever unfortunately in the same position, they would be able to handle it,” he said. “These are all very young ER doctors who are all still learning the ropes, and some of them haven’t even finished their residencies.”

“[Dr. Menes] saw 200 gunshot victims, most of whom were alive, show up at his door in an hour and that’s never happened before, and … what was important for these folks was for them to change the way they thought about how they planned for and deal with that,” said John Gillespie, director of media and public relations at the hospital. “Dr. Menes has a very revolutionary, unique way of thinking about that.”

Specifically, Dr. Menes explained that the method he used to save the roughly 200 people in 2017 was a departure from the centuries-old method of attending to a mass of people who have been seriously wounded through triage.

“The system that is in place for how we should save people in a mass casualty incident actually goes all the way back to the Napoleonic Wars,” he said.

Napoleon’s trauma surgeon, he said, employed a strategy of splitting up soldiers into separate categories that depended on the severity of their wounds: Red, yellow and green. Red patients had the most severe wounds and were the most susceptible to death due to their wounds, green patients could definitely be kept alive with treatment while yellow patients were somewhere in between.

In addition, this method included a separate category for people who were going to die no matter what.

“This sort of mentality has been what we’ve been doing for decades,” he said.

But given advancements in technology, there’s no need to categorize wounded patients in this manner, according to Menes.

“This is the 1800s that we’re talking about, medicine has advanced in lightyears [since then], but we keep this same idea that we can’t save a subset of patients,” he said.

So on the night of October 1, 2017, when hundreds were shot at the concert in Las Vegas, he threw out the old playbook and instead tried to save everyone possible, no matter how severely they were injured.

“That night we didn’t do it that way,” he said. “We figured, ‘How about if we just try to save everybody,’ and whoever doesn’t get saved just doesn’t get saved.”

“Despite having overwhelming odds, we were still able to save every single patient who came into the ER who we could have saved,” he continued. “Really, what we did is just our job. That’s what is expected of us. When people come to the emergency room, we’re going to save them, not just say ‘Hey you know what, you came at the wrong time, everybody else came too, so we’re just not going to try.’ It behooves us as a medical community to try to be able to save everyone.”