Helping Men To Be Fathers

CONEY ISLAND – There’s a new program in Brooklyn helping men be better fathers—and challenging traditional notions of masculinity in the process.

In September, Brooklyn Community Services launched their fatherhood program, an initiative aimed at strengthening the relationships of non-custodial fathers with their children.

The program meets men where they are, from public housing to a local barbershop, and offers twice a week group counseling utilizing the curriculum from the National Fatherhood Initiative, as well as three months of individual case management.

The issue, however, has been getting fathers to sign up for the program, which currently has only seven men, far short of the program’s goal of 60 by year’s end.

Marcelle Craig, director of the initiative, explained why a program specifically for men is needed, and why it’s so hard to recruit.

“Our parenting and family programs attract mostly women. Fathers are often absent from the family because of past incarceration, unemployment, mental health and substance abuse issues, or children from multiple women. This is a men-only space where they can openly discuss their needs, without judgment,” said Craig.

Dr. Diane Davis, who runs the clinical side of the program said the difficulty in recruitment was cultural.

“For men, particularly in the Black and Latino communities, it’s hard to admit they need help. It’s seen as being less of a man,” she said.

Based in Coney Island, the program has outposts in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brownsville, and Downtown Brooklyn, all areas with high concentrations of public housing and potential need.

Alan Dorvil, a case manager for the program, explained that it’s important to be in multiple locations, saying that some men say they can’t come to Coney Island, “because they have “beef” there.”

At a recent meeting of the program at an NYCHA center in Coney Island, the men discussed what was holding them back from a better relationship with their kids, and what they hoped the program could offer them.

Charles, who has six kids with four different women and who lives in a men’s shelter, asserted that he has an excellent relationship with all his kids. His goal is figuring out how to reduce and then pay his child support arrears, currently at $16,000.

But when Dr. Davis pressed Charles to look deeper into his emotional connection to his kids, fissures with at least one child emerged. He explained that he has a girlfriend in the Dominican Republic with a two-year-old son, and he sends them money each month.

“My 19-year-old, he doesn’t like that, he wants to know where the money is for him,” he said.

Minimizing emotional issues and focusing on tangible things, like child support, was common at the meeting. Statistics from the Office of Child Support Enforcement showed 354,000 open child support cases in December of 2016, of which 196,000 were in arrears.

Wayne, a father of two girls, one aged 16 and the other only 18-months-old, each from different mothers, was more open about the emotional aspects of fatherhood, discussing the effects of being separated from his older daughter.

“She’s gotten used to living without me. I try and make plans and she says ‘we’ll see daddy,’” he said, referring to his older daughter. “She doesn’t need me, and that hurts. I don’t want to make the same mistakes with my younger daughter.”

A representative from outreach and paternity services for the city’s child support office, was there to discuss the many fine points of child support with the group, but made sure to impress upon them the importance of owning up to mistakes.

“When I left my family, it hurt my wife. I take responsibility,” he said to whispers from the participants; “that’s right,” and “that’s what a man does.”

“But my daughter is flourishing because I’m a man now,” he said.

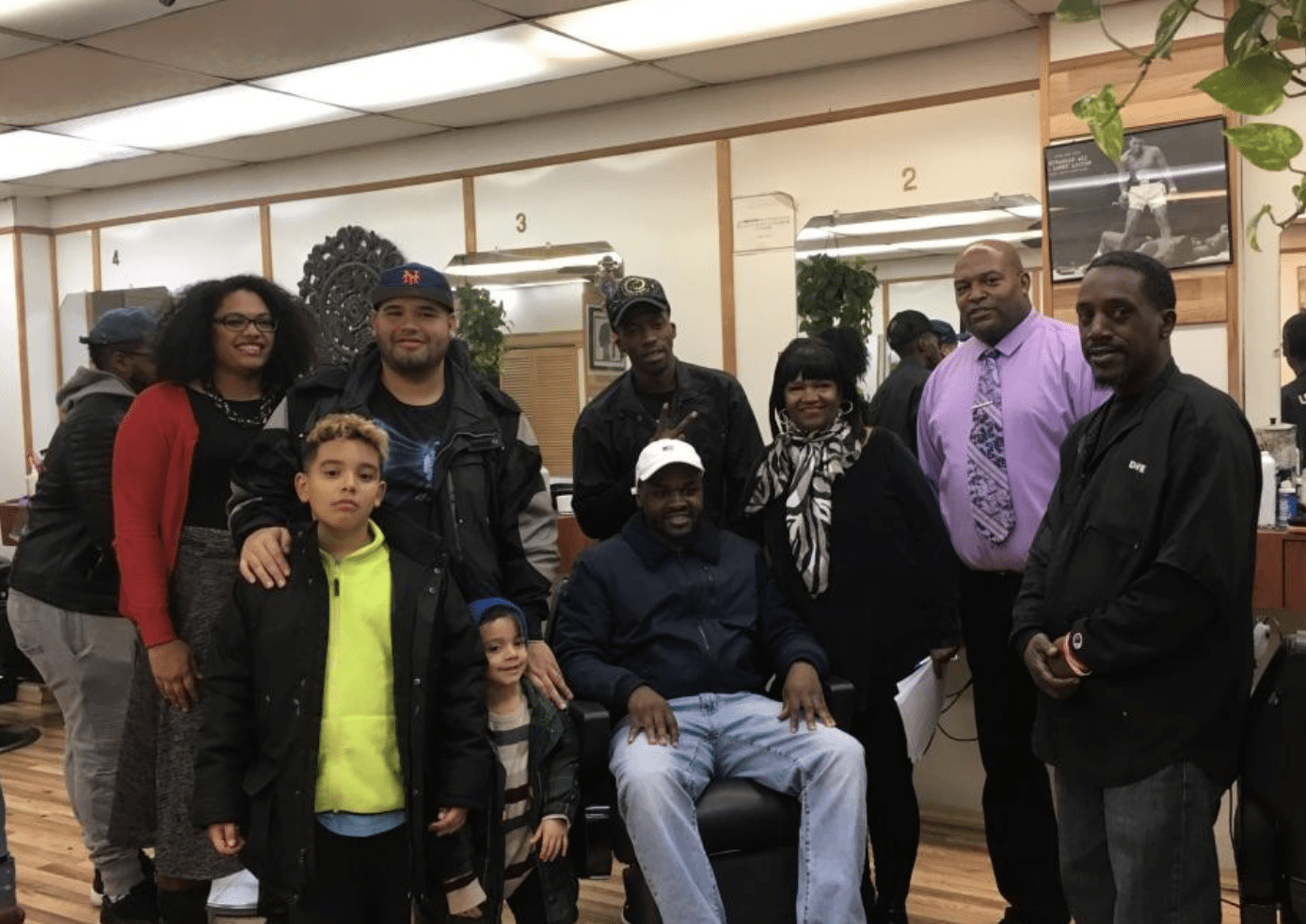

Dr. Davis and Dorvil recently held a recruitment session at Timbuktu Barbershop in Coney Island. They plan to do this weekly until enrollment numbers improve.

Unwitting patrons who happened to come in expecting a quick haircut were treated to a two-hour workshop on fatherhood.

When asked by Dorvil to name important qualities in a father, their answers varied from being a provider and disciplinarian to a leader.

After over an hour, Dr. Davis asked, “What about love?”

The room was silent for a moment, and then a few men indicated love was obvious.

“But it needs to be said,” Dr. Davis said. “Giving love is part of being a father—and a man.”

Close to the two-hour mark, the energy dropped as participants grew weary, but Dr. Davis had one last question for them, representing perhaps the ultimate test of masculinity and fatherhood for this group.

“What would you do if your son was gay?” she asked.

The room snapped back to life as the men roared with uncomfortable laughter.

“I’d take him to a strip club and make sure he’s not into it,” said one. “I wouldn’t want my son to act like this,” said another as he mimed a limp wrist.

The lessons of the session seemed to have seeped in, however. As Dr. Davis told the men that some parents disown their kids for being gay, the group groaned in disapproval.

“He’s still my son,” a man said. “I’d love him no matter what.”

After the session, three men signed up for the program.