Flashback Friday: The 1915 ‘Negro Invasion’ of Park Slope

Edward Reiss, owner of Marine Wrecking Company — meet Walter Kraslow of Kraslow Construction Company.

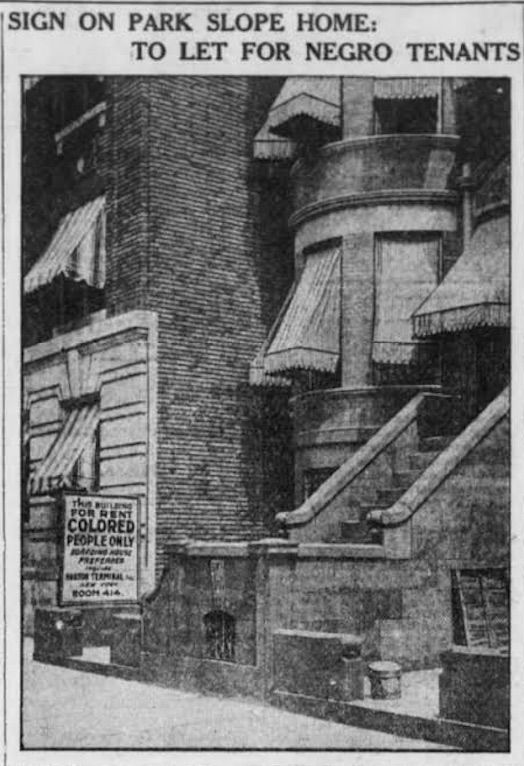

The year is 1915, and the setting is 461 15th Street — just a few houses down from Bartel-Pritchard Square.

Perhaps you walk by this address on the way to a flick at the Pavilion Theater or over to Prospect Park. A sign posted outside the building about a century ago is gone — but it gives us some insight into racial views in our neighborhood from long ago.

Reiss was rather active in the community as member of the Park Slope Civic Association — now referred to as the Park Slope Civic Council. He lived at 461 15th Street with his wife Jennie — a house that had been built only four years before. According to Brownstoner, “[t]he papers referred to the house as a ‘mansion in a highly desirable neighborhood,’ which suggests Reiss may have made some serious upgrades to the home.”

Enter Walter Kraslow, whose construction company began to create the foundation for an apartment building which abutted Reiss’ home.

Reiss and Kraslow got along just fine at the beginning of construction. Brownstoner writes that Reiss “even [let] the crew use his telephone for emergencies and offering cold water to the work horses standing in wagons in front of the house.”

But Reiss became frustrated with Kraslow’s construction. Reiss complained that the sidewalk was being damaged, cement was destroying his roof, and paint from the site was splashed on the front of his building.

While Kraslow agreed to make the repairs, Reiss didn’t think they were done correctly. Fisticuffs ensued and court dates were filed.

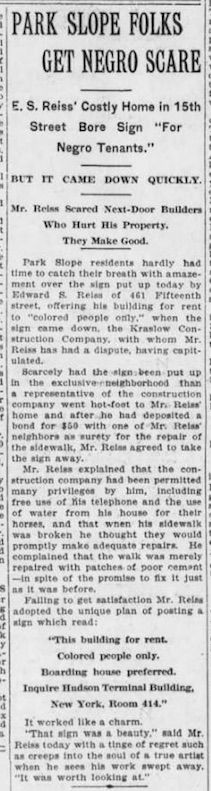

When Kraslow was ready to open the new building to tenants, Reiss was still unhappy with the repairs done on his home. He decided to put up a sign in front of his home that read: “This building for rent. COLORED people only. Boarding house preferred. Inquire Hudson Terminal Building, New York, Room 414.”

The neighbors were upset at the possibility of “colored people” moving into the neighborhood. Brownstone describes Reiss’ actions:

“His heavy metal sign was fixed to his fence, facing his house. He told the papers that he had hired a Negro band to play in front of the house that weekend.

Reiss held court with newspaper reporters, telling them that he had electrified the sign and was, in Reiss’s words, powerful enough to “shake anyone out of his shoes.” If that didn’t do it, he also hired a “250 pound Negro,” who had been ordered to keep people at a distance from the sign.

Reiss told the New York Sun that the reason he had taken these steps was because Kraslow had made the repairs, but had just slapped them together. The cement on his sidewalk was patched with three different colors of cement, and crumbled away after three weeks […]

‘I was warned there’d be a white-cap brigade tonight to tear it down. That’s why I hitched five electric wires of 110 volts each to it. I’ve bought another home at Ninth Street and Prospect Park West, and I’ll be moving into it soon. I don’t care what this costs me.’”

After more court dates and finally an agreement by Kraslow to repair his home, Reiss did coalesce and take the sign down.

The Brooklyn Eagle wrote, “‘That sign was a beauty’ said Mr. Reiss today with a tinge of regret such as creeps into the soul of a true artist when he sees his work swept away. ‘It was worth looking at.'”

The “Reiss-Kraslow Real Estate War” provides insight — disturbingly so — into a slice of our neighborhood history, social mores, and values.