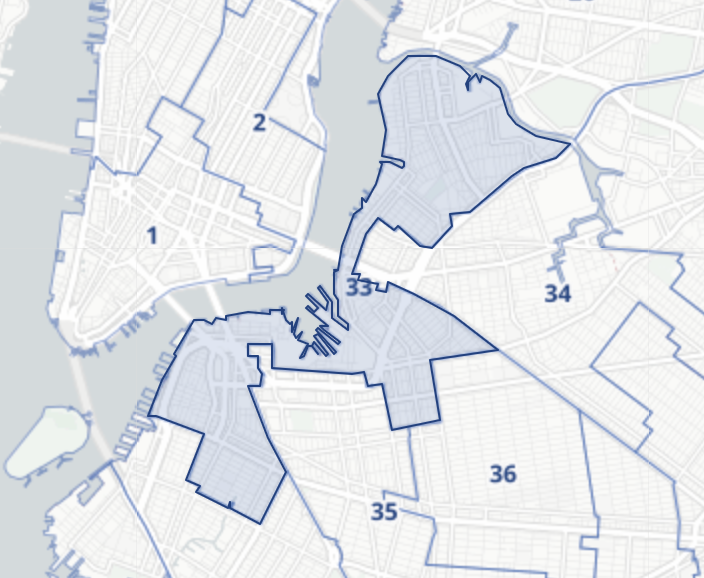

District 33 Council Candidates Have Big Plans for Climate Resiliency

Though climate change and related environmental risks pose a threat to communities throughout New York, the question of how to build a more green and sustainable city is particularly resonant in North Brooklyn.

The area is at the center of a fight over the future of a major fracked gas pipeline proposal; its borders include miles of waterfront that has hosted intense development; it contains superfund sites and an ever-evolving industrial zone; and it has been a focal point in citywide battles over park access and Open Streets initiatives.

Much of this area is encompassed by City Council District 33, so perhaps it’s unsurprising that many of the candidates running to replace term-limited Council Member Stephen Levin in the seat have put a particular focus on climate and environmental issues.

“My top priority is addressing the climate crisis,” one leading candidate, Lincoln Restler, told Greenpointers earlier this year. “We are a waterfront district, and we could very well be deluged by the next big storm.”

Several contenders in the eight-person race have released climate resiliency proposals with ideas ranging from in-home battery systems and new parks to a mandatory organics program and publicly-owned utilities. And while Council Members can’t single-handedly set the city’s environmental agenda, their power to introduce legislation, vote on the city budget and shape land use decisions gives them meaningful influence over how the city tackles this challenge.

Here’s what the candidates have to say about climate change and the environment.

Lincoln Restler

Restler, who works as Chief Strategic Officer for the nonprofit St. Nicks Alliance, says he wants to make CD33 “the first carbon neutral district in New York.”

His campaign has created a 53-point “roadmap” to achieve that goal, which is broken up into several topline categories, including retrofitting old buildings; upgrading the district’s NYCHA developments; expanding tax incentives for rooftop solar panels; legalizing energy storage systems in residential buildings; and providing financing to encourage utilization of electric heat pumps, among other proposals.

There are also transportation initiatives, like providing credits for e-bike purchases and developing a split-level pricing scheme for New Yorkers and tourists on the NYC ferry system.

“When it comes to the climate crisis, our leaders have waited so long and mitigated so little that moderation will fail us,” Restler writes in the plan’s introduction.

Some ideas build on existing legislation, like a proposal to expand a city law that puts strict emissions caps on large buildings to also cover midsize ones, or a push to speed up NYCHA’s timetable for electrifying buildings by 2050. Others have been endorsed by existing leadership, like a proposal to prohibit gas hook ups in newly-constructed buildings, to which de Blasio has already committed.

Still others may pose logistical challenges; Restler calls for legalizing the use of in-home batteries to store solar energy, though a recent proposal to install rooftop energy storage on a Williamsburg building caused an uproar from tenants who said their landlord was ignoring desperately-needed repairs.

Another idea that could provoke mixed reactions: Restler suggests launching an informational campaign to encourage residents to switch to “green suppliers” in the form of Energy Service Companies (ESCOs), private entities that sometimes offer a commitment to renewable energy. But other local leaders, including Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, want to ban or restrict ESCOs from operating in the city, citing high costs, unsavory business practices and questionable impact.

Elizabeth Adams

Adams, a staffer for outgoing Council Member Levin, published a detailed “green recovery plan” in December. While the platform shares elements with Restler’s, including support for mandatory citywide composting and opposition to the proposed North Brooklyn pipeline, there are key differences, too.

For instance, Adams dedicates a section of her plan to eliminating combined sewage overflows, in which a mix of stormwater and untreated sewage discharges directly into city waterways. She wants to install permeable surfaces on public land along Newtown Creek; expand green and blue roof production; and create bioswales on streets along the waterfront.

“Current plans are using rainfall totals from 2008 as projection for infrastructure that is supposed to address stormwater capture in the 2040s,” she writes.

Adams also supports the “public power” campaign to take government control of the city’s utilities; the idea has support from Williams and the Democratic Socialists of America, but state legislation to make it happen faces an uncertain future.

Other proposals include pausing development in the city’s flood-prone areas until the government reforms the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) process, with the goal encouraging “open spaces, resiliency projects, or wetland restoration centers,” and an emphasis on “comprehensive citywide resiliency planning.”

Adams also suggests providing funding for community gardens and protecting them “from harassment and land alienation”—a response to recent pleas from community garden operators who have asked the city for legal protections against development.

Toba Potosky

Beyond Restler and Adams, candidates’ plans get a little less dense. Toba Potosky, a co-founder of the Cadman Park Conservancy with a wide-ranging professional background, has built his sustainability platform around a cute acronym, which we’ve reprinted below:

- Growth – Let’s create pilot programs that combine wind, solar, tidal and hydrogen fuel cells.

- Renewable – Investment in the development of more renewable energy sources.

- Efficiency – Create X-Project programs that focus on increased efficiency.

- Empower – Empower small businesses and residents to make better, more sustainable choices.

- Neutrality – Implement smart and cost-effective strategies to meet NYC’s goal to [sic] carbon neutrality.

“Each year brings new technology and new, exciting opportunities to reduce our carbon footprint and fight climate change,” Potosky’s website reads. “Our mission is to reduce carbon emissions while investing in cleaner, more renewable energy sources.”

That big-picture language might resonate broadly with voters, but some of Potosky’s specific proposals could ruffle feathers.

For instance, Potosky has called for the creation of a north Brooklyn seawall, a coastal barrier intended to protect the borough from flooding “from Greenpoint to Red Hook,” an idea that received some pushback at a forum earlier this month. He also dodged a question from Habitat Magazine earlier this month about the financial impact of the city’s ambitious Climate Mobilization Act on co-op and condo boards.

Stu Sherman

The Sustainability section on the online platform of candidate Stu Sherman, an attorney, includes some of the same positions mentioned by Restler and Adams, like opposition to the North Brooklyn pipeline and investments in composting programs.

But he’s also got some unique ideas. Chief among them: greening the city’s film and television industry.

“As the heart of New York’s film industry, we must support a tax incentive for carbon neutral features, building a film set/prop recycling center in the district, and require electric generators for filming on any city owned or maintained property,” Sherman writes.

The city has taken nascent steps in this direction; in 2016, the city launched “NYC Film Green,” a voluntary program that gives productions a certificate and a seal enrolled if they successfully implement certain sustainability practices.

Other Sherman proposals include using retractable bollards to make Open Streets permanent; investing in infrastructure to reduce combined sewage overflows; and funding green retrofits for NYCHA and private buildings.

His platform also mentions electrifying the city’s vehicle fleet—something the city committed to early last year—and supporting “no-motor vehicle infrastructure.” Sherman’s definition of such infrastructure includes protected bike lanes as well as underground vehicle parking for vehicles, though many traffic experts believe creating more parking simply encourages more driving.

April Somboun

April Somboun, a marketing and communications strategist, is the only person in the race to have the backing of a mayoral candidate—she and Ray McGuire, a former Citigroup executive, endorsed each other earlier this week.

In tweets highlighting the endorsement, Somboun wrote that she and McGuire shared a vision for transforming the crumbling Brooklyn-Queens Expressway into “a greenway belt” that “provides diff modes of transportation eg bike/walk lanes, connects to the waterfront, and helps us meet our climate goals.”

We envision a greenway belt that help us combat climate change, provide sustainable communities and affordable homes; one that creates economic growth and a safer and healthier quality of life for all. pic.twitter.com/Vy4aJsl7ZT

— April Somboun (@aprilsomboun) May 23, 2021

That’s more detail than Somboun had previously offered in her online “Contract with District 33,” which mostly focused on community engagement regarding the plan.

Likewise, the Contract’s “Climate” section is relatively brief and broad.

Somboun wants to restore GrowNYC’s zero waste programs, many of which were suspended during the pandemic. She suggests providing tax incentives to encourage net zero building construction, though the city and state already offer financing and incentive programs for green investments, and the 2019 Climate Mobilization Act will force most large buildings to significantly reduce their carbon footprint without incentives.

Somboun also mentions pushing “state and private companies in NYC to fully divest from fossil fuels,” but doesn’t say how. And her plan to improve public transit includes pushing the MTA to expand the G and L lines, a highly unlikely proposition; if the MTA does manage to build more subway mileage in the coming years, it will likely focus elsewhere.

Ben Solotaire

Ben Solotaire, like Adams, works in the office of outgoing Council Member Levin, for whom he serves as Community Liaison and Director of Participatory Budgeting (he’s committed to allocate all his discretionary funding to the PB program).

Beyond the concerns about sewage overflows and polluting peaker plants shared by many candidates, Solotaire’s platform to “rebuild and repair our environment” calls for mandating the construction of green roofs on new and existing buildings “wherever possible,” and to offer a buyback program for gas stoves that would be replaced by electric ones.

He also suggests the city “expand usage of waterways and railways for freight delivery and transportation” to reduce traffic congestion and air pollution; an existing, $100 million city program designed to do just that is expected to launch this year after a pandemic-induced delay, though experts have mixed opinions about whether it will succeed.

Victoria Cambranes

The first bullet on Victoria Cambranes’ five-point plan to protect the environment calls for “a local Green New Deal from Greenpoint to Gowanus as a massive ‘Green-Collar’ jobs program.”

But the “massive” program is defined in only one sentence: “Actions such as retrofitting all public buildings with new technologies and mandating LEED certification for all new buildings (using union labor), will fight climate change while putting people directly to work.” In other interviews, she has also mentioned cleaning Superfund and Brownfield sites, sewer overflow, and educating students about green infrastructure.

Points two and three call for increased funding to the city’s Department of Environmental Protection and creating “bio-diverse habitats and natural underwater flood barriers.”

In point four, Cambranes proposes a “carbon budget” that sets long-term emissions targets, and sounds quite similar to the aforementioned Climate Mobilization Act, which requires around 50,000 of the city’s buildings to cut emissions by 80% by 2050.

Point five suggests Cambranes will “eliminate visual corridors that make waterfronts feel private and inaccessible” and ensure park designs are not “de facto private or inaccessible,” though it’s not clear how doing that would protect the environment.

Sabrina Gates

Though Sabrina Gates writes on her website that a commitment to sustainability “must be at the forefront of how we engage in every issue moving forward,” she’s the only candidate in the race without a published climate or resiliency platform.

Her campaign also did not respond to a request for comment on this article.

In a questionnaire completed earlier this month on parks and green space issues, Gates spoke broadly in support of green roofs, installing solar panels in park spaces and offering additional composting sites.