Deal Reached On Controversial Tax Credit For Affordable Housing Construction

(This story was updated on 11/16/16 with a map of areas impacted by 421-a affordable housing requirements.)

After lengthy negotiations, a tentative deal has been struck on a New York City tax credit which has been used to incentivize the construction of affordable housing.

The Real Estate Board of New York and city construction unions have reached an agreement on the 421-a tax credit program, which provides housing developers with a significant reduction in their New York City property taxes. The program expired last year, and must still be renewed by the New York State legislature.

The program has required developers in certain neighborhoods to construct some affordable housing as part of their projects.

“The deal reached…provides more affordability for tenants and fairer wages for workers than under the original proposal. While I would prefer even more affordability in the 421-a program, this agreement marks a major step forward,” Governor Cuomo said in a statement.

Wages were at the crux of the 421-a negotiations between developers and the building trades unions. Under the deal reached last week, developers who receive the credit must pay an average hourly wage of $60 (this includes benefits) to workers constructing buildings in Manhattan, and $45 to workers in Brooklyn and Queens, Curbed reported.

The wage deal applies to new buildings with 300 or more apartments, Curbed noted. Buildings in Brooklyn and Queens Community Boards 1 and 2 — “within a mile from the nearest waterfront bulkhead” — are covered by the wage requirement; in Manhattan, new buildings south of 96th Street are also included.

Developments that offer more than 50 percent of their units as affordable can opt out of the wage requirement, Curbed said.

How 421-A Works

The 421-a program was originally launched in 1971 to stimulate housing development in New York City, which was struggling with population loss and private sector disinvestment at the time.

As property values recovered and construction surged, the 421-a program was modified in order to extract some affordable housing from development in areas where it was argued that housing would be built whether an incentive was provided or not.

In exchange for receiving a partial break on real estate taxes through 421-a, new developments in a defined Geographic Exclusion Area must provide some affordable housing — at least twenty percent of units.

The areas where some affordable housing is required under the 421-a program include:

— All of Manhattan

— Brooklyn: Downtown Brooklyn, as well as portions of Red Hook, Sunset Park, Fort Greene, Prospect Heights, Park Slope, Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, Boerum Hill, East Williamsburg, Bushwick, East New York, Crown Heights, Weeksville, Highland Park, and Ocean Hill.

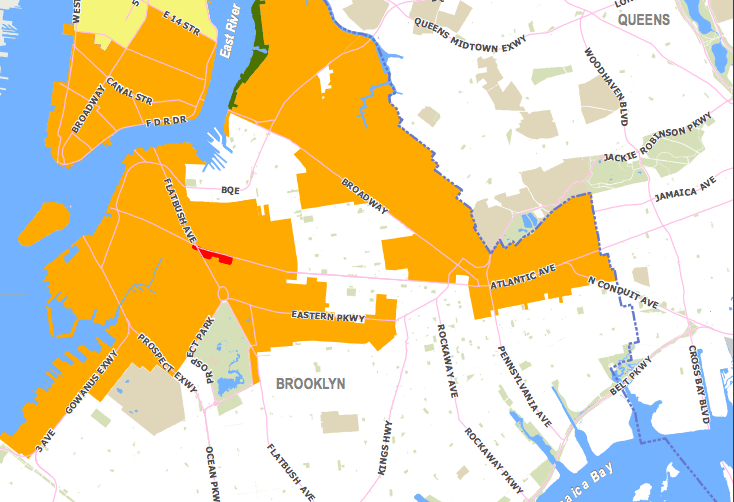

The orange shading in the map below shows the sections of Brooklyn included in the Geographic Exclusion Area, meaning there is an affordable housing requirement for developers.

The red sliver off Flatbush Avenue is the Atlantic Yards Arena Project, which has “special” affordable housing provisions. The Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront also has a “separate Waterfront Exclusion Area in effect since 2005, with different affordability requirements.”

— The Bronx: portions of Claremont and Crotona Park.

— Queens: portions of Long Island City, Astoria, Woodside, Jackson Heights, and the East River Waterfront.

— Staten Island: portions of St. George, Stapleton, New Brighton, and Port Richmond.

Until the 421-a program expired last year, developers who built affordable units could obtain an exemption for up to 25 years from the increase in real estate taxes that would have normally resulted from the new development. The deal reached last week could increase the length of the exemption to 35 years.

Under the existing 421-a guidelines, all market rate rental units become subject to rent stabilization for the duration of the benefits. In addition, affordable rental units must remain rent stabilized for 35 years, the City states in its guidelines. The deal reached last week would increase this to 40 years. Changes to program income requirements would also enable more lower-income individuals to qualify, Governor Cuomo said last week.

Mixed Record

Providing developers with decades worth of tax breaks to build affordable housing in New York City’s overheated real estate market remains controversial — as does the fact that housing developers outside designated areas receive the tax credit no matter what.

Curbed noted last week that applications for new residential developments “plummeted” in 2016 after the 421-a program expired.

The program is believed to have real impact — forty-two percent, or 5,885 of the 13,755 affordable units built in New York City in 2014 and 2015, were facilitated by 421-a tax breaks, Curbed reported in May.

But some elected officials have questioned whether tax breaks are the most effective way to encourage affordable housing construction. In 2014, the Manhattan Borough President’s office estimated that only 14 percent of all 421-a tax-exempt units are affordable to lower income households. “The impact of 421-a on new construction of affordable housing…remains minimal,” the BP’s office maintained two years ago.

New York City currently foregoes 1.1 billion in property tax from the 421-a program — “a sum that has exponentially grown since its inception in 1971,” the BP’s office added.

Another issue raised by critics of 421-a is whether developers are complying with the program’s requirement that affordable units be designated with the State as “rent-stabilized.”

A lengthy analysis by Pro Publica last month reported that two-thirds of the 6,000-plus rental properties receiving tax benefits from the 421-a program “don’t have approved [421-a] applications on file and most haven’t registered apartments for rent stabilization as required by law.”

Affordable housing developer, Community Preservation Corporation, called the 421-a program “far from perfect,” but added in a statement last week that it “has been critical to making rental development financially feasible, creating mixed-income communities, and spurring low- to moderate-income housing production in the outer boroughs.”