‘Criminal Injustice System’ Alive and Well: Wrongfully Convicted Crown Heights Man Discusses Biopic

CROWN HEIGHTS – It’s an understatement to say that there are significant problems with the nation’s criminal justice system.

As of last year, 151 exonerated prisoners had served a combined 1,639 years behind bars for crimes they did not commit, according to data compiled by The National Registry of Exonerations, which tracks all exonerations from 1989 onward. Official misconduct occurred in at least 107 of those cases.

Although blacks account for about 12 percent of the U.S. population, they represent 61 percent of the 367 inmates exonerated by DNA testing since 1989, according to the Innocence Project.

Those statistics are all too familiar to Colin Warner. In 1980, he was an 18-year-old immigrant from Trinidad wrongfully convicted of murder by a criminal justice system that wanted a conviction—not the truth. After several failed appeal attempts, he finally won his freedom in 2001.

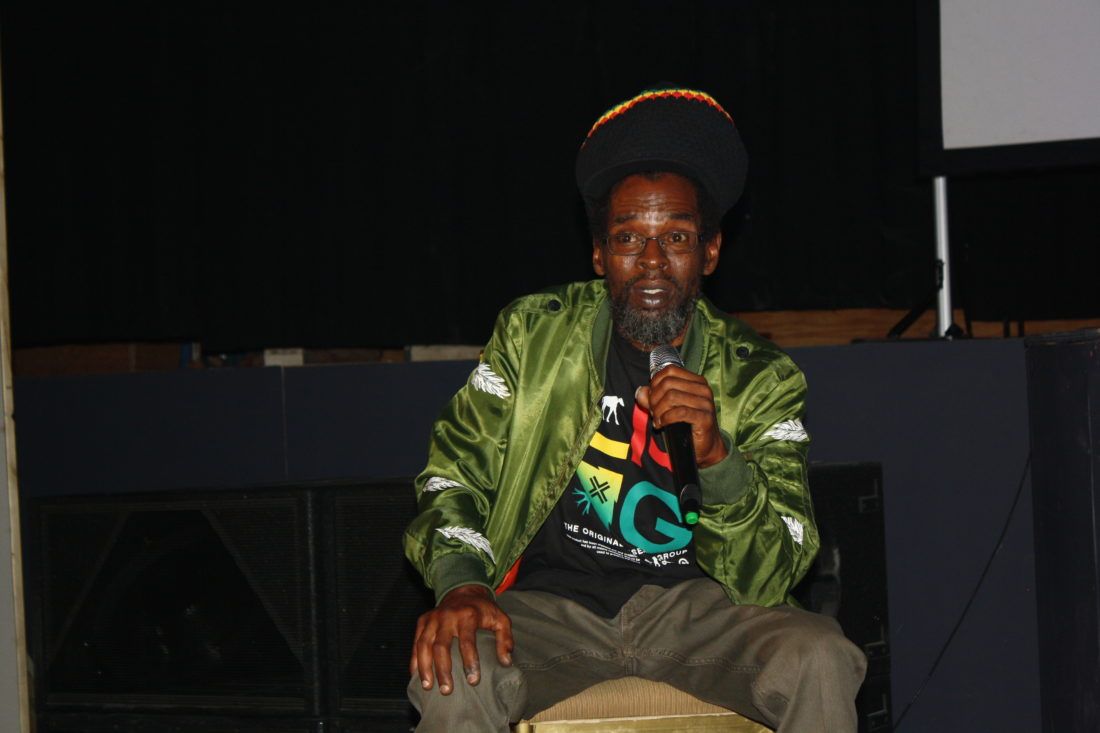

On Sept. 19, The Black Lady Theatre on Nostrand Avenue hosted a free screening of “Crown Heights,” a film about Warner’s ordeal. After the viewing, he led a panel discussion that included his lifelong friend, Carl King, who spearheaded the 21-year campaign for Warner’s release.

“This film is a teaching tool about the system of injustice,” Warner told the audience of about 50 people at the event sponsored by the Nostrand Avenue Improvement Association.

He warned that the same system that incarcerated him in 1980 is alive and well four decades later.

A jury convicted Warner and co-defendant Norman Simmonds for fatally shooting Mario Hamilton outside Erasmus Hall High School in Flatbush in April 1980. The prosecutor used the testimony of an alleged witness–the victim’s brother, Martell Hamilton–to get a conviction.

Two decades later, through King’s perseverance, Simmonds confessed that he was the gunman. Martell Hamilton also admitted that detectives pressured him to give false testimony against Warner who was not involved in the shooting.

The film, which was released in 2017, tells Warner’s story against the backdrop of elected officials and law enforcement agencies calling for drastic measures to combat a wave of crime in the 1980s and 1990s.

Many are now questioning the legislation and crime-fighting tactics that resulted in mass incarceration. It has come to light that coercing witnesses and framing innocent suspects were often used to get convictions.

Former NYPD Detective Louis Scarcella, once a celebrated Brooklyn homicide investigator, has become a symbol of the injustices of that era. The disgraced detective now stands accused of framing at least eight people, but that’s likely just the tip of the iceberg.

King, who immigrated as a teenager from Trinidad, recalled that in the late 1970s after the Vietnam War ended, some cops wore military jackets and would drive up to young black men standing on corners in Brooklyn and tell them to get off the streets.

“Colin was kidnapped [by the police] from the street,” King continued. “And there was a presumption of guilt from the start.”

Things haven’t changed much, panelist Esmeralda Simmons told the audience on Thursday night, adding that police stop-and-frisk tactics have declined but racial disparities in who gets stopped still exists.

“What they do in our neighborhoods, they don’t do in Staten Island. They don’t do it on the Upper Westside or Upper Eastside. They don’t do it in Park Slope or Howard Beach, said Simmons, the founder and executive director of the Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College.

She continued: “This is not really about criminal justice. This is about an entire system in our society that perpetuates slavery. The name they call it is mass incarceration, but what it really is, they go around and enslave us.”

Simmons, who grew up in Crown Heights, urged some black residents to reevaluate their thinking of how the police operate in their community.

“Unfortunately, many of us who have experienced violence in the neighborhood think police picking up young men off the street is a good thing. It’s not a good thing. There is no justice in the criminal justice system,” she said.