Council To Vote On New Street Food Vendor Bill

The City Council is voting tomorrow, January 28, on a street food vendor permit bill. The bill, which was first proposed in 2018, will gradually expand the number of permits to vend food in the streets of New York City from 3,000 to an additional 4,000 vendors over the next ten years. The permits will begin to be issued in 2022 and will be delivered over the course of the next ten years. One supervisory license must be present at every pushcart at all times.

The bill will also create a new dedicated “vending law enforcement unit,” which will work solely to enforce vending laws. The use of enforcement agents follows after de Blasio’s announcement to move vendor enforcement out of the NYPD so that officers can “focus on the real drivers of crime instead of administrative infractions,” according to a June announcement by the mayor.

A street vendor advisory board will also be created by this bill to “assess the effectiveness of the enforcement unit and the roll-out of new supervisory licenses, and examine and make recommendations pertaining to vending laws,” according to Intro 1116 of the bill.

De Blasio said that the bill is something he has wanted for a long time, in a press briefing on Monday.

“A balanced plan to support street vendors, but with clear ground rules, strong enforcement, and clear accommodation for bricks and mortar, small businesses, and there’s been a lot of discussion in the last weeks with the council,” said de Blasio.

“I think we’re in a good place. I think we’re getting now the kind of balance that we’ve needed all along. So, I’m very hopeful about this legislation. I’m certainly aware that small businesses have gone through hell, and we need to protect them at this moment. I think this legislation, as I’ve seen it so far, has been written in a way that does that,” he added.

The bill will lift the 3,000 permit cap that former mayor Ed Koch placed on street vendors in 1983. This cap placed on vendors resulted in black market rates for the $200 permit up to $25,000. The new licenses will first be delivered to already existing vendors who have flaws with the “current regime,” Intro 1116 says.

The bill, which is baked by 30 council members, including Carlos Menchaca, Brad Lander, Antonio Reynoso, Inez Barron, Mark Treyger, Justin Brannan, Stephen Levin, Mathieu Eugene, Alicka Ampry-Samuel, and Laurie A. Cumbo, will directly help Brick and Mortar businesses who were shut out of economic relief such as Wael Elbeab, who has owned Food Ford, a halal food cart located on the corner of Metropolitan and Bedford Ave, in Williamsburg, since he moved to New York from Egypt seven years ago.

Elbeab said that the city does not care about street food vendors, so many turn to the black market. To solve the problems of vendors turning to the black market to rent their carts, Elbeab said, the city should give more permits to street food vendors in boroughs other than Manhattan.

“The people come from Manhattan, and they come, work in Brooklyn,” said Elbeab.

Another problem he sees with the current system is the fact that by the rules, carts are movable and spots are available on a first-come basis. “There is no writing in my permit or my license,” that says Elbeab can always park his car on the corners of Metropolitan and Bedford ave. If he wants to take the place of the street food vendor next to him, he can.

Elbeab said that he parks his car at his location every day by 9 am. If someone is in his spot, he fights with them. He’d like to see the solution to include permit locations for street food vendors, said Elbeab. If he could have a permanent location, Elbeab said that he could relax, go to sleep, and then come back to work the next day.

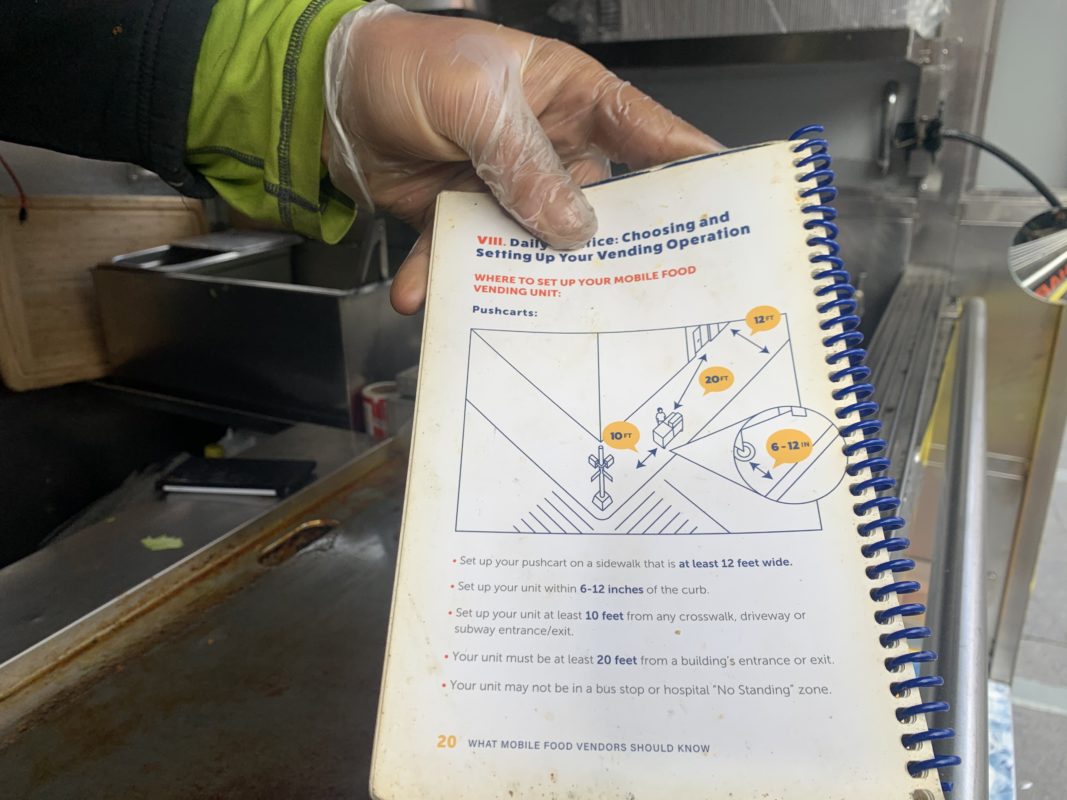

Local restaurants on Bedford ave also affect Elbeab’s business. The food vendor booklet, which Elbeab keeps with him, requires vendors set up at least 20 feet from a building’s entrance.

If Elbeab were to get too close to the nearby Apple Store, or a restaurant, workers can call the police and complain, he said. “They didn’t even speak with you. Why?” said Elbeab.

For struggling restaurants on Bedford Ave, such as Anna Maria Pizza, street vendors have impacted their business. Owner George Acosta, who opened Anna Maria in 1997, said over the phone, “I was the first guy to stay open till three, five in the morning.” In the past three years, night business on Bedford ave has been very bad, said Acosta. Since the pandemic began, Anna Maria’s business is down 50%, said Acosta.

“The rent is too high,” said Acosta, “we’re giving the guy, the vendor in the street, the opportunity to make a living. Okay, I want to make a living, everyone wants to make a living. But then, he (vendor) is taking away from us,” said Acosta.

As more street vendor permits are created in the city, there will be “nothing for us,” he added. “The business is going to go down, we’re gonna lose employees, and people aren’t going to be able to pay their rent,” said Acosta.

“My business has been open for twenty-four years. Now all of a sudden, in the neighborhood I have ten vendors around the corner and only one business. My business is going to go down, 20%, 30%. That’s the problem we have in Williamsburg right now,” said Acosta; “I want everybody to make a living, but what is the cost?”