Bushwick’s William Ulmer Brewery Set to Become a Maker Space

The historic William Ulmer brewery will become a maker space for Bushwick artisans by late 2021.

Bushwick has been synonymous with makers for almost two centuries – the talented, scrappy individuals, often new to the country, who produce excellent brews, coffee, and food, along with art, furniture, and other handmade goods.

Everything about the iconic Ulmer brewery – from its origin story, to the architect who built it– is a striking reminder of a time when Bushwick was first brimming with immigrant hard work and ingenuity, and it is being reimagined as a space for the next generation of makers.

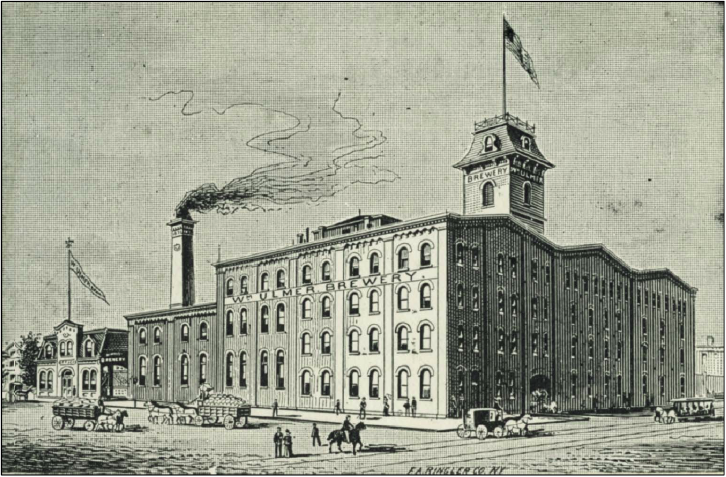

The brewery, which consists of four buildings on Belvidere, Beaver, and Locust streets, was co-founded in 1871 by William Ulmer. The buildings were constructed between 1872 and 1890 by German architect Theobald Engelhardt in the German round-arch style common in Brooklyn breweries at the time.

Ulmer first immigrated to the U.S. from Germany in the 1850s, and gained his entry into the brewing business by learning to make lager-style beer alongside his two uncles, according to a Landmarks Preservation Commission report. Within seven years, Ulmer became the sole proprietor of what had grown to be one of the largest breweries in Brooklyn, significantly expanding the business in the 1880s and 90s to increase capacity, at one point taking up over half the block. He gave it a new name: the William Ulmer Brewery.

The fact that William Ulmer brewery was run by a German immigrant was far from unusual at the time. “By the 1870s, Brooklyn had become a major force in American beer brewing, as numerous establishments, largely run by Germans, flourished in the borough’s Eastern District (Williamsburg, Greenpoint and Bushwick),” the Landmarks Designation Report reads. Bushwick produced 10% of all beer in the U.S. up until 1940, and much of it came from German-run breweries.

The brewery closed in 1920 after the Prohibition Act came into effect, as did many of Brooklyn’s other breweries. At its peak, though, it was consistently churning out 3.2 million gallons of beer yearly, and was one of the most successful breweries in the neighborhood. In spite of its untimely end, Ulmer’s was the best-known brewery in Bushwick, and the only one in New York City to become an official landmark.

Now, in moving forward with the new plans for the brewery, the landlords — MacArthur Holdings, Rivington Partners, and Brightsky Investments, who acquired the building in 2018 for $14 million — are hoping to turn the space into a platform for Bushwick’s artisans and makers to create and thrive. To execute this idea, they’ve hired New York design firm DXA studio, run by co-founders Jordan Rogove and Wayne Norbeck.

“So much of what we do when we get our hands on these landmark buildings,” Rogove said, “is to create a dialogue with contemporary design and culture with [the periods] that preceded it, through our architectural intervention.”

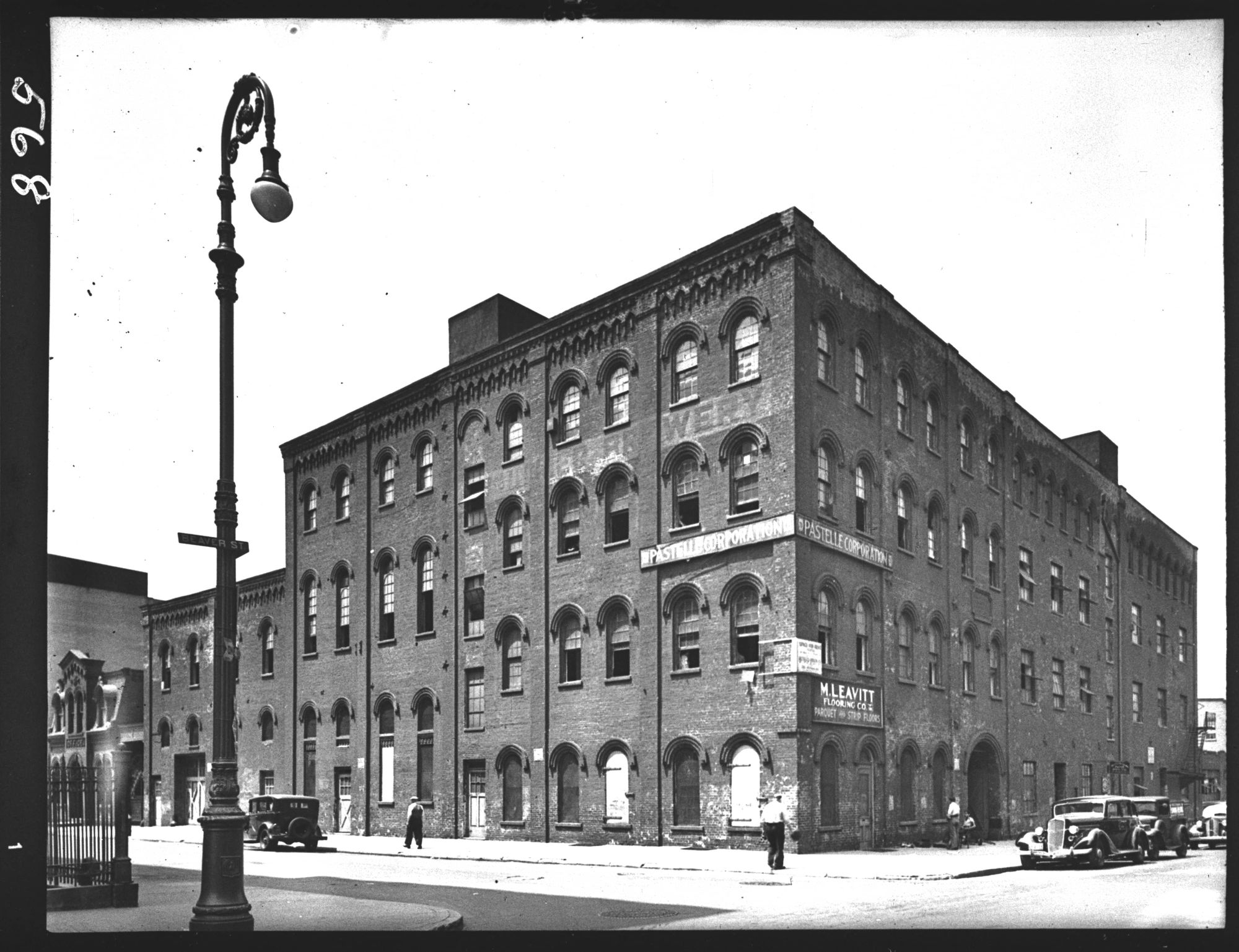

Before they did any planning, the partners first dove headfirst into historical research. The building, Rogove said, “had its heyday pre-prohibition.” When prohibition hit, “They did these horrible renovations or alterations to the building to make it pure manufacturing.”

To restore it to its original state, the architects needed to size up every detail of the original brewery – not an easy task considering they had nothing but old photos to work with. And then there was tracking down the photos themselves. Rogove said they eventually found a collection of impressively high-res photos, not in any municipal archive, but, bizarrely, in an Australian man’s eBay shop.

Once they had their hands on the photos, they set to work measuring window mullions and frame details. On a larger scale, though, they needed to make sure that the building was fully modernized, as well as accessible. The building’s original purpose was as, essentially, “a machine for making beer,” Rogove said, and so the floors were built in order to accommodate all the equipment. This means that none of them line up. An ideal setup for making beer, less so for tenant use.

In spite of its shortcomings, the team found plenty about the building worth holding on to: exposed brick, pressed-tin ceilings, timber and cast-iron columns and beams, and the vaulted-ceiling brick rooms below street level, which once housed barrels of beer at the perfect temperature.

Beyond the building’s charms, what ultimately enticed Rogove about the project, he said, was “the relationship between those guys in the 1870s and the guys that are in Bushwick now, making beautiful furniture, making incredible food – there’s commonality between these two periods in the city’s history.”