Brooklyn Rabbi’s Family Losses Fuel Personal Quest to Enforce COVID-19 Safety Measures

By Reuven Blau, originally published by THE CITY

For Rabbi Robert Blustein, enforcing mask-wearing in his synagogue is personal.

Blustein lost both his parents and an older sister to COVID-19 — and doesn’t want anyone else from his Brooklyn community to experience similar grief.

“I’m more sensitive to it. I’m trying to protect people as much as I can,” said Blustein, 51, the rabbi of the historic Ocean Parkway Jewish Center in Kensington.

The shul is located in the 11218 ZIP code, one of the 20 hotspots in Brooklyn and Queens where the number of people testing positive for the coronavirus has risen in recent weeks.

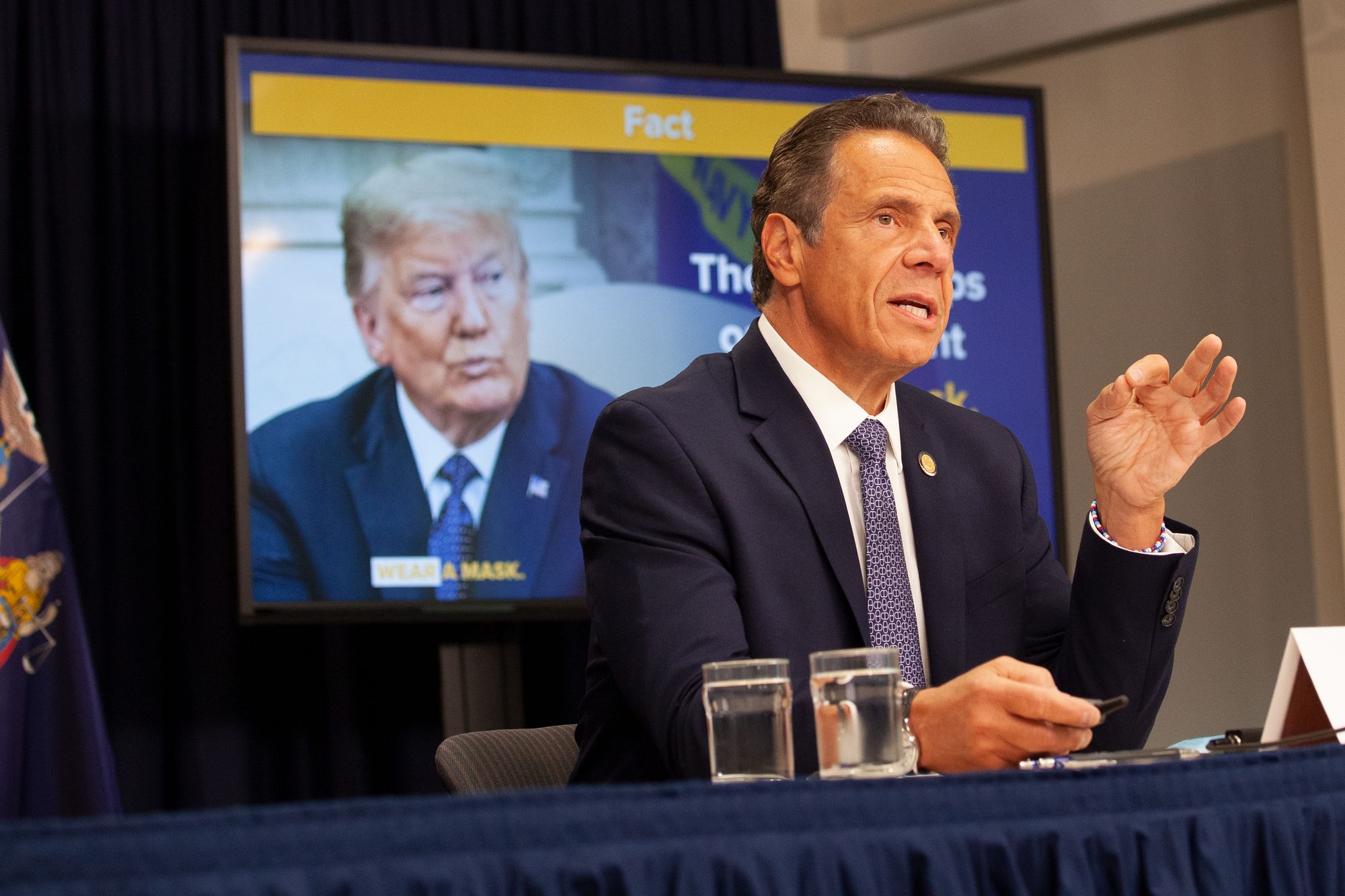

On Monday, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced that about 100 public and 200 private schools in nine of the ZIP codes with the highest rates would be closed beginning Tuesday — a day earlier than Mayor Bill de Blasio had planned. He nixed de Blasio’s call, though, to shutter non-essentials businesses in the areas.

The neighborhoods covered by the nine ZIP codes account for more than 25% of new coronavirus cases in the city over the past two weeks, despite representing 7.4% of the city’s total population, according to the city Health Department.

“These clusters have to be attacked,” Cuomo told reporters. “New York City has clusters.”

Cuomo pointed out that the city has conducted over 2,000 inspections of businesses in a bid to get people to wear required masks in public, issuing 26 violations and 883 warnings.

“Too many local governments are not doing enforcement. Warnings are not enforcement,” he said. “You will see people die if we don’t do more enforcement.”

Shuls and other houses of worship will be allowed to remain open as long as reopening regulations, including operating at 50% maximum capacity, are followed, he added.

“I have to say to the orthodox community tomorrow, if you are not willing to live with these rules then I’m going to close the synagogues,” Cuomo said, noting he’s enjoyed a “very close” personal relationship with the community for decades.

“This is the last thing that I want,” he added. “Forget about politics.”

City Hall Seeks Rabbi’s Help

As for the Kensington synagogue, a representative from City Hall reached out to Blustein hours before the start of the joyous Sukkot holiday on Friday night, the rabbi said.

The official wanted to know if the city could turn the parking area in front of the synagogue into a COVID-19 pop-up testing site, said Blustein, who forwarded the call to the shul’s president. The conversion is unlikely because the building doubles as a school for Hasidic children during the week.

As for the call from City Hall, Blustein said the official also asked him to encourage his congregants to wear masks and stay six feet apart from each other during services.

The official didn’t need to remind Blustein, who lives out on Long Island in West Hempstead during the week and stays in Brooklyn on the sabbath.

Days before the shul shut down in March, Blustein walked around offering spritzes of hand sanitizer to members, and encouraged frequent hand washing.

When the synagogue reopened in May, Blustein was taking care of his ailing mother. But he advocated for a series of safety measures — including the installation of hand sanitizer dispensers throughout the synagogue and enforcement of the mandatory mask rule.

Some seats in the main sanctuary were marked off-limits with Xs to make sure people would keep at least six feet apart.

He also suggested requiring all congregants given honors during the service, like opening the ark or saying a blessing before the Torah reading, to wear gloves.

After months away, Blustein returned for a late night service last month, the week before Rosh Hashanah, and for prayers on the High Holy Days.

“There were a lot of times on Rosh Hashanah I had to go around with masks and tell people they had to wear them,” he recalled. “I had to explain to them that it’s a rule and they have to allow the rabbi to establish the safety protocol — and beside that, it’s the law.”

“By and large, they put the mask on,” he added. “I suspect some people were doing that because of my personal take.”

‘I Was Trying Not to Cry’

The rabbi’s father, Abraham Blustein, 85, became the first in his family to get sick with COVID-19, months after a stroke sent him to Golden Gate Rehabilitation on Staten Island.

In late March, he began to struggle to breathe a few days after being transferred back to Brielle, an assisted living facility nearby, where he resided with his wife and daughter.

The elder Blustein died a few days later on April 1.

“I spoke to him the day before he passed away,” Blustein said. “He was very alert but I couldn’t see him. They were on lockdown.”

His sister, Diane Broughton, 64, also became sick and died four days later in Staten Island University Medical Center. The two funerals were held days apart.

The family kept the news from the rabbi’s mother, Gladys Blustein, 87, who was struggling with a series of medical issues when she contracted COVID-19.

Rabbi Blustein, who wore a torn shirt as a traditional sign of Jewish mourning, changed his attire before visiting her, standing outside while communicating through a window.

“I was trying not to cry,” he recalled.

She passed away in late August, about three weeks before Rosh Hashanah.

The Rabbi’s Two Masks

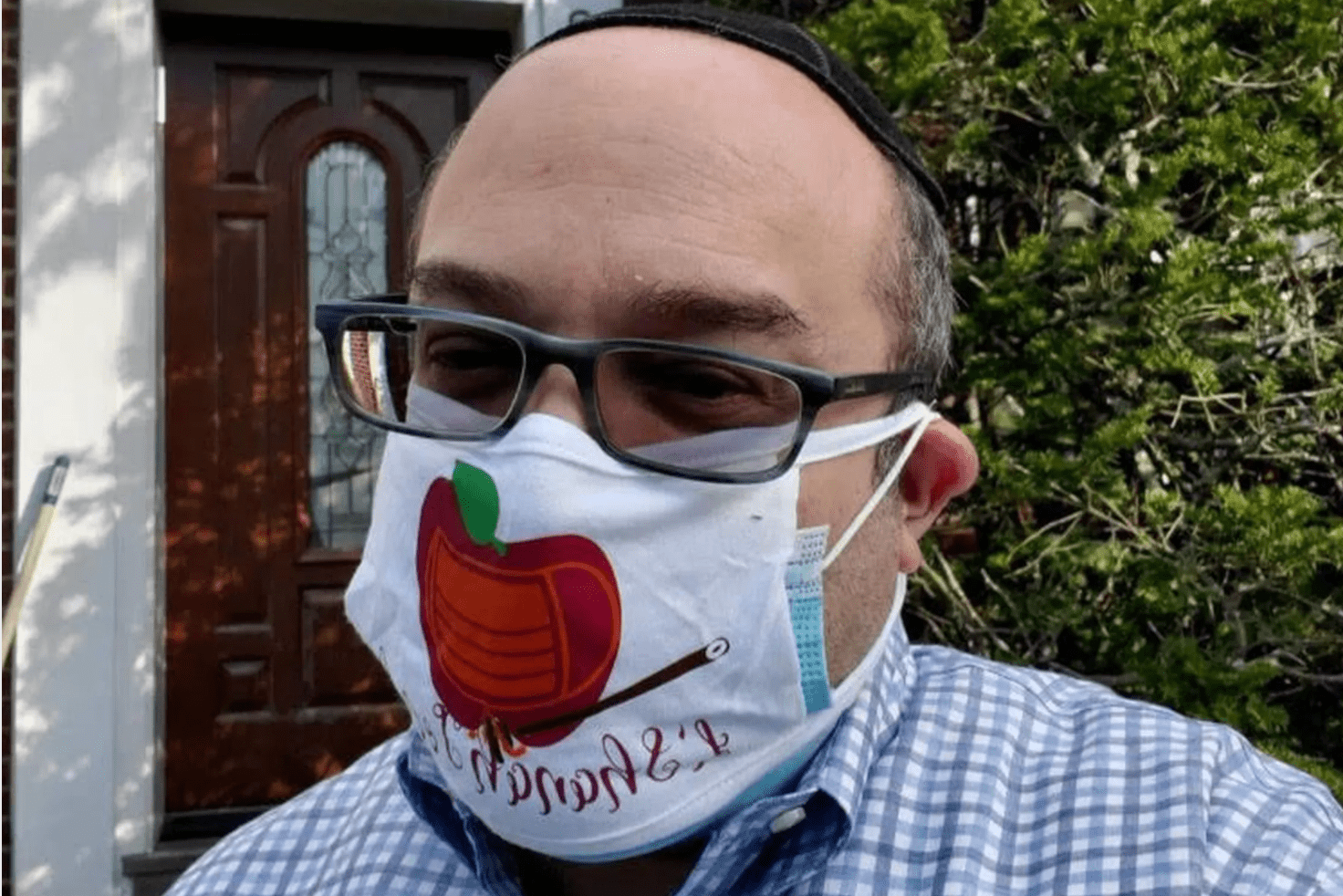

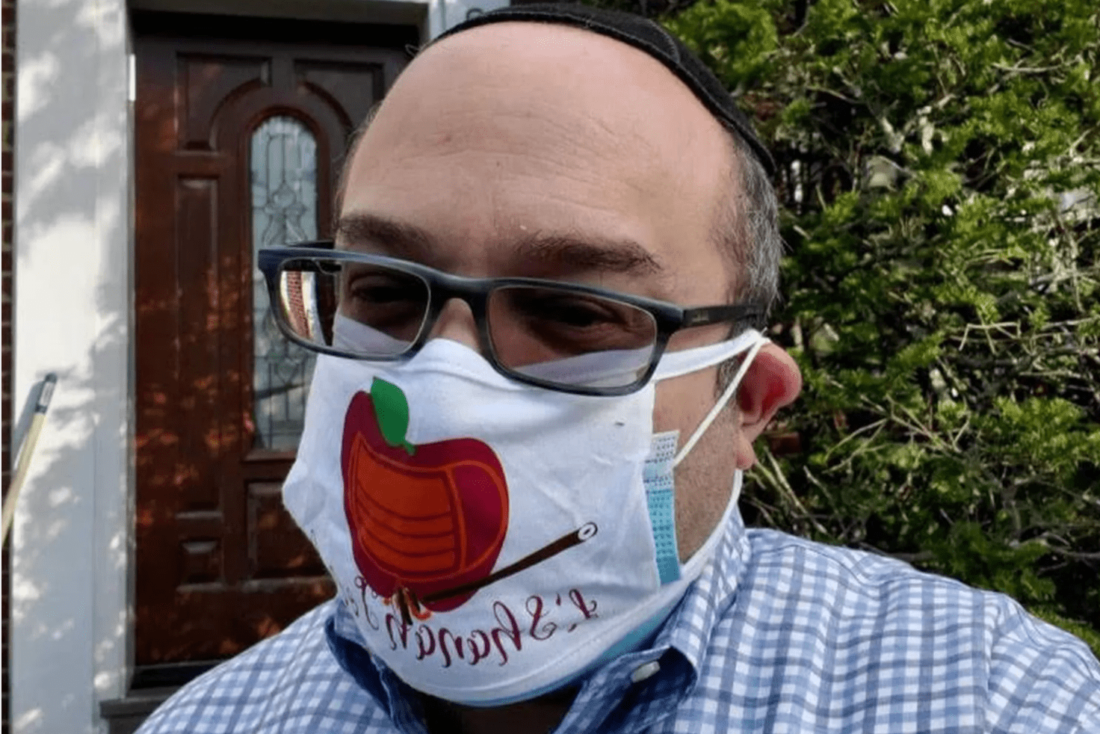

In shul, Blustein has taken to wearing two masks: one topped with a cloth covering wishing everyone a happy new year and another one that reads, “Please talk in shul, but only to Hashem,” using a synonym for God.

On Sukkot, one congregant refused to wear a mask and ignored Blustein’s pleas to put one on.

“When you insist on not wearing a mask, you are potentially putting other people at risk,” Blustein told him. “I didn’t get into a shouting match. I just kept on telling him he was violating the rule. I was trying to enforce safety.”

Blustein, who has been the rabbi of the main minyan in the building since June 2003, said he did his best to convince the man to abide.

“I’ve never in my life thrown somebody out of shul,” he said. “I told him he’s not welcome to come.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.