Brooklyn Leads in Child Care Deserts, Comptroller Report Finds

BROOKLYN HEIGHTS— There aren’t enough child care centers for residents of low-income areas of the city, Comptroller Scott Stringer said Wednesday while talking up his plan—which, if implemented, would subsidize child care for many New Yorkers— to child care providers and advocates.

Stringer met with the Day Care Council Advisory Committee and child care providers to pitch his recently released proposal, NYC Under 3”—an initiative that aims to close the gap between families who need child care and resources available to them.

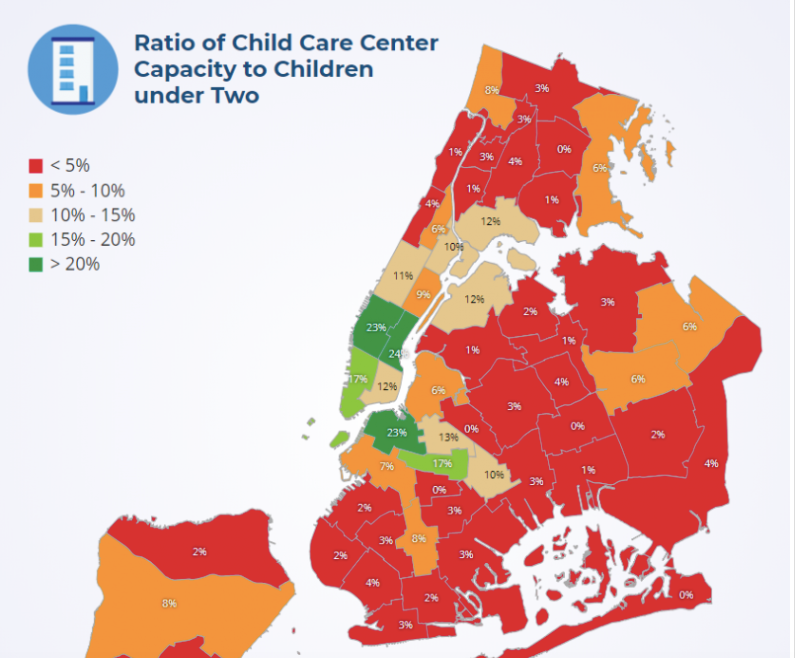

Stringer’s report finds that there are only enough child care centers for 6 percent of children under two in the city, and that the problem is particularly acute in the less well-heeled parts of Brooklyn.

Indeed, seven of the top 10 most child care-starved neighborhoods, according to the report, are in the borough: Bushwick (3), Brighton Beach and Coney Island (4), Bay Ridge and Dyker Heights (5), Greenpoint and Williamsburg (6), Crown Heights South, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, and Wingate (8), Borough Park, Kensington and Ocean Parkway (9), as well as Sunset Park and Windsor Terrace (10). In these neighborhoods, there is an ample amount of day care space for just 5 to 8 percent of children, according to the report.

“If you look at the childcare deserts, it’s no accident where these child care deserts are. It’s almost predictable,” he said in Brooklyn Heights at Day Care Council’s monthly meeting. “And that’s [due to] lack of investment.”

Stringer lamented that, while vacant storefronts, transportation infrastructure, and luxury development dominate the political conversation in New York, the lack of child care centers and funding is, in his telling, absent from it.

“It’s not on anybody’s radar,” said Stringer, a likely top-tier mayoral candidate in 2021.

The proposal, released last month, would provide affordable child care for an additional 70,000 families in New York, Stringer says. The $660 million annual cost of the subsidy program to provide free or discounted childcare, depending on their income, for families with yearly earnings of up to $103,000, would be funded via payroll tax on big businesses.

Currently, center-based child care in New York City cost roughly $21,000 a year per child, which would eat up about 70 percent of a full-time working, minimum wage-earning single parent’s income, according to Stringer’s report. The plan, the comptroller said Wednesday, would have the added benefits of allowing working-class parents— mothers in particular— to enter and remain in the workforce during their kids’ infancies.

Stringer has the support of three legislators, including Assembly Member Latrice Walker of Brooklyn, who in a press release said Stringer’s initiative would “provides families with high-quality, affordable child care that will alleviate the stresses that are caused by the rising costs of child care providers.”

Of the reasoning behind the funding mechanism for the policy, Stringer told Bklyner that it’s “important that we have a consistent revenue stream,” so that funds aren’t “held hostage … in the city and state budget dance.”

“I do support a small tax on the wealthiest businesses—95 percent of businesses would be exempt—but I’m open to working with the business community to come up with different revenue streams,” he went on.

During the meeting, Stringer spoke about his own experience paying for child care for his young son, noting that it presented a significant financial burden for even his relatively well-off family. He also touched on other subjects tangentially related to the struggles families with young children face, particularly in gentrifying neighborhoods.

“When luxury development comes into a community at a rapid pace, we worry about the people in the existing community,” he said. “We don’t want people to get priced out.”

Those at the small meeting were mostly receptive to his proposals, saying they were pleased an issue important to them was getting its due attention.

Alice Owens, president of Colony-South Brooklyn Houses—a nonprofit social service group—said she was pleased more attention was being given to child care for young children “because that’s where the greatest need is.”

“I think they’re wonderful starting points,” she said. “There was a lot of research in [the report].”

“We’re very supportive of the comptroller’s proposal,” said the executive director of Day Care Council of New York, Andrea Anthony, who said that, while Stringer may be facing an uphill climb in the legislature and governor’s mansion, he has a shot of getting his idea approved, due to the comptroller’s gathering of support from three assembly members. “I think he has a good chance, because he’s starting early.”

Can he get this done in Albany, where progressive-policy dreams often go to stall and die? Would this be a plank of his potential mayoral campaign platform? His plan could get started before 2021, Stringer insisted.

“I have two and a half years to serve as city comptroller,” he told reporters after the meeting. “I believe we can begin this proposal before my term ends. I’m not thinking about this [for] down the line. I’m thinking about working with the state government to build this today.”