BQX Community Meetings Ahead Of April Environmental Review: Here’s What’s Proposed

The Brooklyn-Queens Connector (BQX) proposal to build a streetcar along the Brooklyn and Queens waterfronts is moving forward with a community engagement process ahead of an environmental impact review in April of this year.

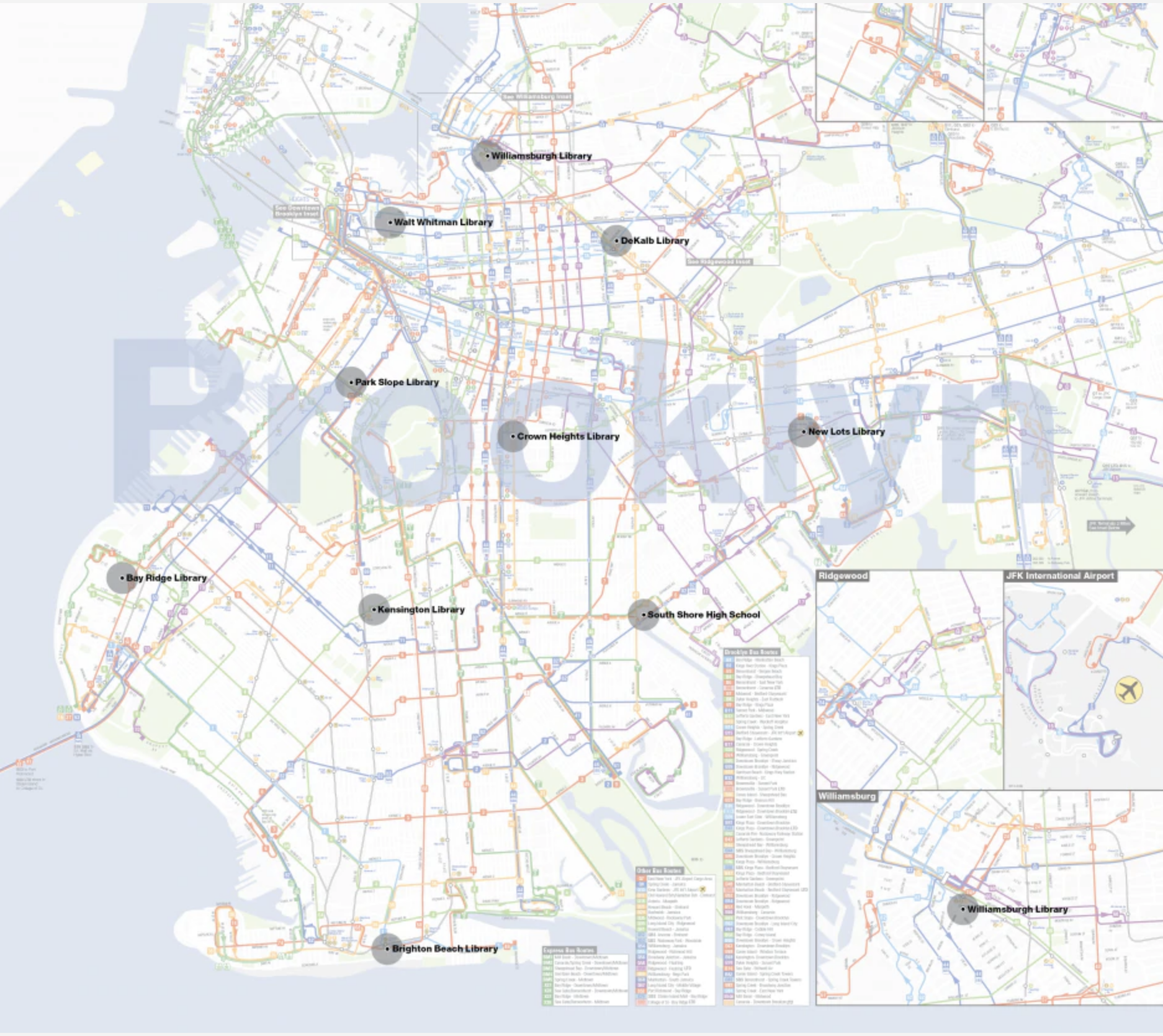

The city’s Economic Development Corporation (EDC) and Department of Transportation (DOT) have already visited two of the three Brooklyn community boards where the streetcar would pass through, and plan to hold five “community engagement workshops” in February and March along the route.

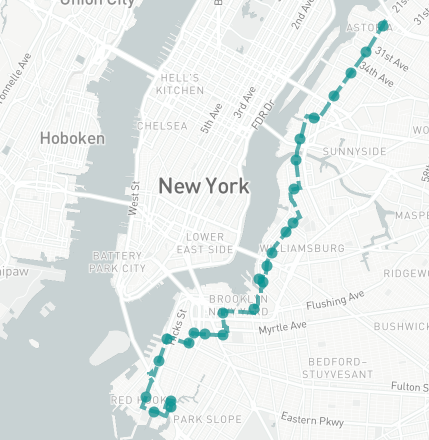

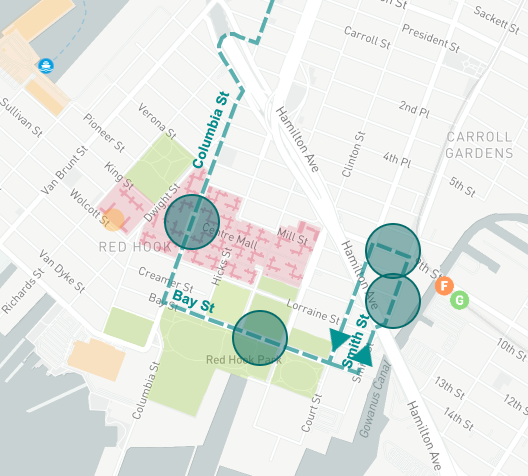

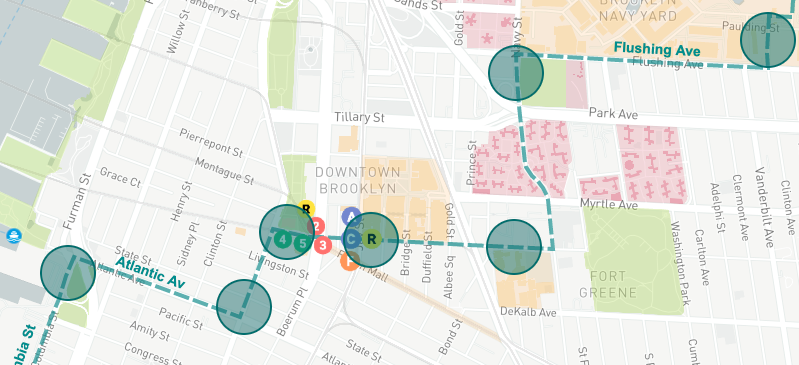

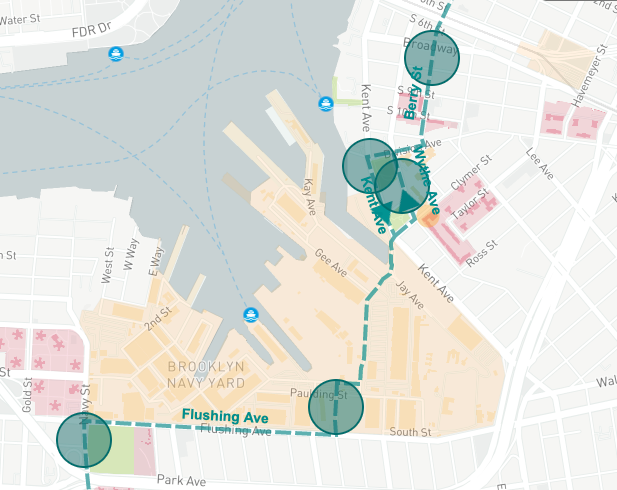

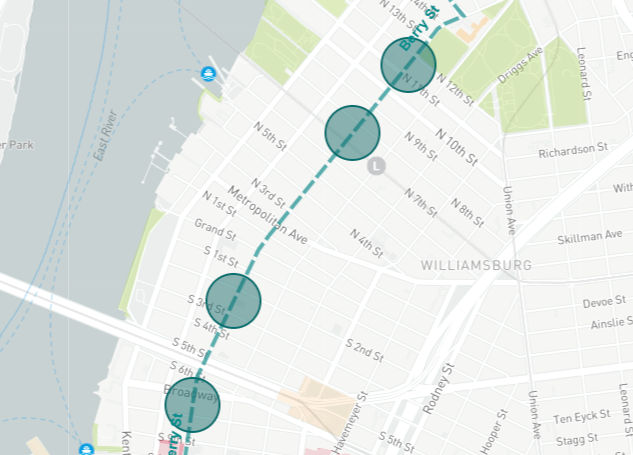

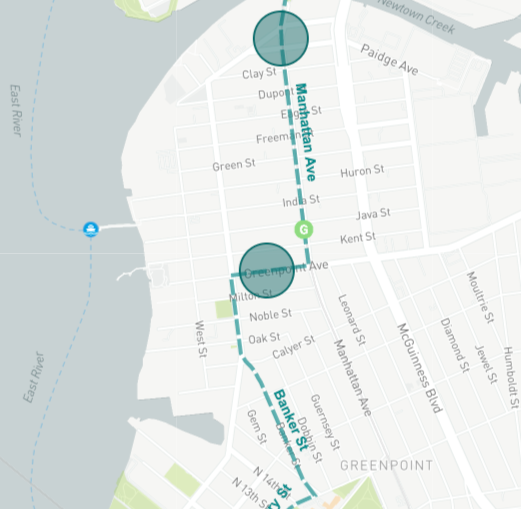

The streetcar, first proposed in 2016, would provide a new north-south connection along the fast-growing Brooklyn waterfront that is currently home to some 400,000 residents. After years of false starts, with public engagement hearings derailing amid community opposition, and the route shedding its Sunset Park portion, the city is trying again. The proposed 11-mile route would connect Red Hook, Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, Downtown Brooklyn, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Williamsburg and Greenpoint in Brooklyn, before crossing Newtown Creek on a newly constructed bridge and passing through Long Island City and terminating in Astoria, Queens.

City officials tout that it would travel through transit deserts such as Red Hook, the Brooklyn Navy Yard area, and western Astoria. Other benefits noted include the streetcar operating along an exclusive right-of-way for 90% of its route, short wait times, ADA-accessible boarding, and emission-free operations. Though it would be owned by the city and operated by EDC, the fare would be pegged to that of the MTA subway and buses, and free transfers would be available between the streetcar and the numerous subway and bus stops along its route.

The project is projected to cost $2.7 billion, and the timeline doesn’t estimate construction to begin until 2024, and the streetcar would only go into operation in 2029, nearly eight years after Mayor de Blasio leaves office. Among de Blasio’s potential successors, Borough President Eric Adams supports the streetcar, while Council Speaker Corey Johnson is a critic. Comptroller Scott Stringer has not taken an explicit position.

The administration originally posited that it could be entirely financed via “value capture,” or increased property taxes tied to increased property values along the route, but now concedes that at least half would have to come from the federal government’s New Starts grant program; the program will have to be tailored in such a way that it is eligible for the grant.

The main group supporting and advocating for the project other than the city is the Friends of the BQX, chaired by Jed Walentas, CEO of the developer Two Trees Management. Two Trees has been developing residential and mixed-use buildings along the waterfront in Williamsburg including the massive Domino Factory site, and lately, the River street project that would involve converting a former Con Edison site to a mixed-use residential building that would be tallest in North Brooklyn and creating a new park. These and other developments – old and new – would benefit from easier access.

“With the BQX heading towards its public review process, 2020 promises to be a big year for the project. Engaging with those who live and work along the route is critical to the BQX’s success, and we applaud the city for putting together a robust outreach plan for the coming months,” Claire Holmes, a spokesperson for Friends of BQX told us. “From transit advocates and public housing leaders to business owners and civic groups, the BQX has a broad and growing range of supporters. As more New Yorkers learn about the project over the next few months, we expect that support network to keep growing.”

The project also has support from cultural organizations like the Brooklyn Public Library and BRIC, and business groups like the Association for a Better New York and the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, as well as NYCHA tenant leaders along the proposed route, and transit groups like Regional Plan Association.

Opponents of the project range from various anti-gentrification and anti-development groups to business groups like the Atlantic Avenue Business Improvement District, who are concerned about the permanent loss of parking, and released a statement opposing the project painting a doomsday scenario:

“The impact on Atlantic Avenue businesses would be devastating because of the disruption of commerce during the construction, reduced customer access to stores, reduced ability of stores to receive deliveries, and the permanent loss of on street parking. Retail and restaurant businesses would not be viable because of the possible 10 year construction period, the subsequent lack of public on street parking, and the loss of customers to more accessible competitors.”

At the Community Board 6 meeting in Red Hook last night, the same concerns were brought up as before. Some said the project is for the waterfront’s wealthy, white residents and would be a harbinger of gentrification.

Others criticized it as an unnecessary addition to the city’s transit landscape, noting that the streetcar would run along a very similar, parallel path to the G train for much of its route. The city’s ridership estimates land at 80,000 per day, about half that of the G train, though city officials note that the streetcar would be fully accessible and ADA-compliant unlike the G. The streetcar would travel at a paltry average speed of 12 mph, potentially slower than a cyclist.

The common theme among opponents of the streetcar is the alternative — expanded bus service.

“Buses, buses, buses,” Laurie Mutchnik-Maurer, an architect, told Bklyner at the Community Board 6 meeting where the city gave a presentation on the streetcar. When the audience at the CB6 meeting on Thursday was asked whether they were opposed to the project, nearly every hand in the room shot up.

“It’s clear that an electric streetcar provides the best solution to connect people between Brooklyn and Queens along this corridor, both in terms of infrastructure, routing, and ridership,” said Holmes. “The streets along the Brooklyn Queens waterfront are complex, indirect, and highly trafficked, with traffic signals and irregular loading. Any bus service, SBS or not, would face serious delays, traffic and irregularity in service. SBS routes are only effective along straight, wide corridors and ill-suited to the narrow streets and tight turns of the Brooklyn-Queens waterfront. Nor do buses have the capacity to accommodate the anticipated BQX ridership, with an anticipated daily ridership of 60,000 people. A streetcar, on the other hand, has the ability to not only move the projected ridership but also expand with it along the corridor in a single, efficient route with a dedicated right-of-way.”

Better bus service may still be in the corridor’s future. The city is still looking into adding Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), possibly even a busway, as an alternative to the streetcar, according to Chris Hrones, the Director of Strategic Transit Initiatives at DOT, and DOT is revising all of the Brooklyn Bus Routes this year.

However, Hrones told Bklyner that the public engagement process was not meant to gain support for the project, but to gather input on how best to implement it.

“We’re not really out here to sell the project per se,” Hrones said. “We’re out here to present what we have now and hear what people have to say. And we take their feedback seriously.”