Behind Paul St. Savage’s Sneaky Subway Art

In New York, a city that fancies itself the art capital of the world, it’s no surprise that artwork presents itself almost everywhere, including the workaday subway car. A recent “B” train outing to Coney Island, for example, revealed an unexpected payload: cleverly slipped into an advertisement poster holder was an arresting image of six figures with a stylized “St. Savage” signature floating in the center.

Contemplating this image for the duration of the 30-minute trip, it finally occurred to me that this wasn’t a fanciful promotional piece for children; it was someone’s original art.

So I stole it.

Once home, I examined my illicit take. The figures—simply drawn in black marker on white poster board—had a playful familiarity, perhaps explaining why I mistook it for an unusual subway advertisement. Which, as it turns out, it was, marketing the work of one Paul St. Savage,also known by the tag “ANGRY EEL.”

An artist and illustrator living in Brooklyn the past 19 years, including 18 years in the Clinton Hill/Fort Greene area, St. Savage acknowledged via email that he had indeed installed art on the train I happened to ride that day, part of an extended campaign where the artist posted subversive (and clever) work in subway cars along the B, D, F, G, and Q lines.

“I don’t have a title for it, but I usually just call it subway art or public art,” St. Savage said. Then, quickly becoming conspiratorial with me, he suggested, “We can coin a term too for fun. Maybe ‘Sneaky Art’ or ‘Sneaky Subway Art.’”

Though he may consider his art sneaky, St. Savage hopes it will have a profound impact on the casual observer.

“These posters will hopefully grab someone’s attention and make them smile,” St. Savage said of his subway series, which he’s been doing for the past five years. “They’ll use their brains and senses. If I can make someone look twice at my work and they take a picture or take it home, that’s fantastic. If they wonder: ‘What the hell is that doing there? Who did that? What’s it mean?’ that’s even better.”

Interact with Paul St. Savage’s latest work of public art, a Sing For Hope Piano! It will be sitting inside Brower Park, across from the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, from June 5 through 21, ready for you to play it!

With a lineage stretching back to Paleolithic cave paintings in France, graffiti art remain a New York City constant. Shepard Fairey’s slick, mass-produced images of Andre the Giant (OBEY!)—ubiquitously plastered around the city—have spawned a multi-million dollar apparel industry. Last year the anonymous English graffiti artist Banksy, in a highly publicized, month-long New York residency, installed his work at multiple sites, though some were quickly defaced by local graffiti artists. The work of Cost and Revs, two old guard practitioners from the 90s, still dominate the city’s landscape, their tags seemingly on every NYC lamppost or building.

“I wouldn’t call my art on the subway graffiti,” St. Savage said. “Graffiti (especially on trains) is lettering, words and names. I’m a lifelong fan of illustrative art and political cartoons. I like to express and communicate feelings, moods and social commentary. In society—and especially in NYC—I’m bombarded with ads, lifeless printed images selling products and digital brainwash. I feel that real deal art made from the human hand is a reminder that society needs to stay in touch with thinking, acting and living for themselves.”

In the 1990s, St. Savage attended Pratt Institute and watched as the surrounding Clinton Hill neighborhood was transformed, so much so that last year he relocated to Flatbush.

“I have mixed feelings,” St. Savage said about the changes. “I dislike the greedy overdeveloping, high rents and pseudo-spring break type of vibe, but I also welcome new quality eateries, increase in safety and a bigger art audience.”

“I loved gritty NYC, but this is all inevitable, albeit a bit floodgate-like,” St. Savage observed. “The changes in my surroundings are some of many things that influence my artwork.”

Like others, St. Savage romanticizes the 70s, known as the golden age of New York City graffiti.

“I’m a lifelong fan of the graffiti-covered subway cars I saw growing up,” Savage said. “That era was really mysterious and mesmerizing. The whole concept of your work being brought around town to the masses on a subway full of humans. Adding something to the sullen aura. Effecting what the commuters thought and felt.”

The work I stole exhibits a casual but confident style, from its bold marker lines to its whimsical characters. “My illustrations are characters, scenarios, feelings and moods. Some are metaphors for realities I see in the world and all around me. Life is packed with these things, and I wanted to give them a form,” he said.

Then there’s his tag, ANGRY EEL, which St. Savage likens to logos such as the Rolling Stones’ juicy tongue or Black Flag’s distinct four bars, but with added significance.

“The EEL watches and observes,” the artists said. “He slithers throughout town. Big Brother watches us, but the eel is watching him back. He is the central scrutinizer—a Frank Zappa reference—and he stays in the creative trenches.”

St. Savage’s public work is a way to pay homage to artists he admires while broadcasting to fellow New Yorkers his own distinctive message.

“I’ve never fully appreciated mainstream art, manufactured art or images made by a team of nondescript artists for mass revenue purposes,” he explained, “that’s why I set these posters loose in the streets and trains for free. It’s a gift to NYC. A message in a bottle. It’s more powerful than a gallery wall—something to look twice at and think about. Stark black-and-white images displaying the creeps, lurkers and underlying moods of our city and nation. I’ve taken the cue from personal favorites like Raymond Pettibon, Richard Hambleton, Spy vs. Spy and Krazy Kat, just to name a few.”

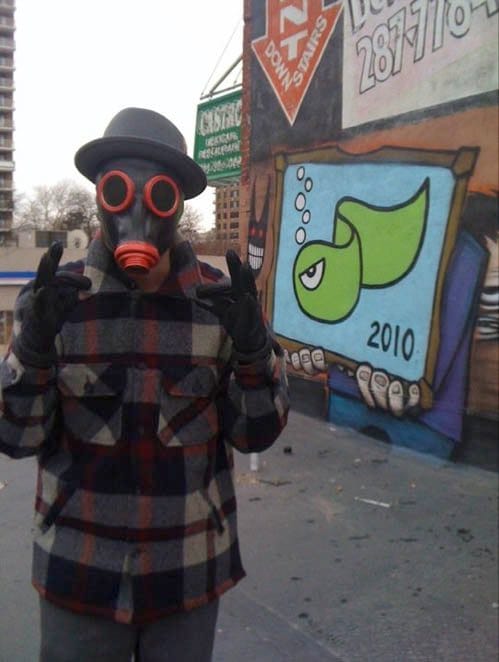

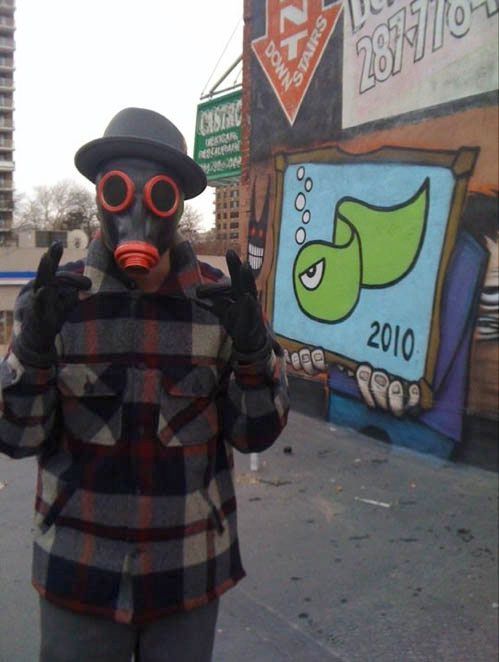

“Overall, it’s my own little idea for contributing to the vast history of illustration, artwork and NYC street culture,” said St. Savage, who—like many graffiti artists—values anonymity; he’s pictured on his website wearing a mask. “All the stuff that I grew up on and that inspired me, I’m putting my version of it back out into the world for others to view.”

And, perchance, to steal.