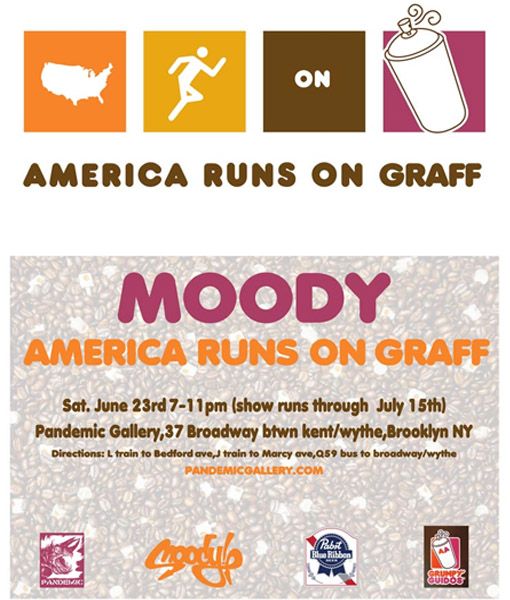

“America Runs On Graff” – Bensonhurst Graffiti Artist’s Gallery Show Opens In Williamsburg

He’s a local terror. He’s been bombing Bensonhurst since the 80’s. And now he’s got an art show in Williamsburg.

The house was packed on Sunday at the Pandemic Gallery at 37 Broadway. The audience wasn’t the usual group of art snobby purveyors but a younger, rougher set.

It was white undershirts, SB Dunks, sharpies, blackbooks, and the barely healed over acne of youth. The crowd was there to see the work of Mutz, or Moody, a graffiti vandal turned street artist and now, gallery artist.

“He’s a legend,” said a barely 16-year-old kid from the Bronx. “He’s been bombing since the 90’s.”

Actually Mutz, has been bombing even before that. He grew up in Bensonhurst, under the watchful and woeful eye of his mother and he’s been spray-painting his tag throughout the neighborhood since he was barely a teenager in the 80’s.

“He was always getting into trouble. I bailed him out so many times. Worrying about him writing graffiti was hard, but I’m proud of him, he’s an artist,” she said.

The difference between the 80’s and 90’s may not seem long, but traction in the world of graffiti art is a measure of success. Walls are buffed regularly, storefront gates get painted, kids get locked up. That Mutz pieces can still be found throughout Bensonhurst is a testament to the virtues of his form.

It’s opening night and this is Mutz’s second gallery showing since transitioning from late-night bombs to daytime painting and sculpting. He changed over from bomber to street artist when he started installing his woodcut bubble letter “M” to abandoned factory walls and poles throughout the city. Since then, he’s shown at Woodward Gallery and created a body of work that blends his graffiti heritage with a new-found criticism of modern culture.

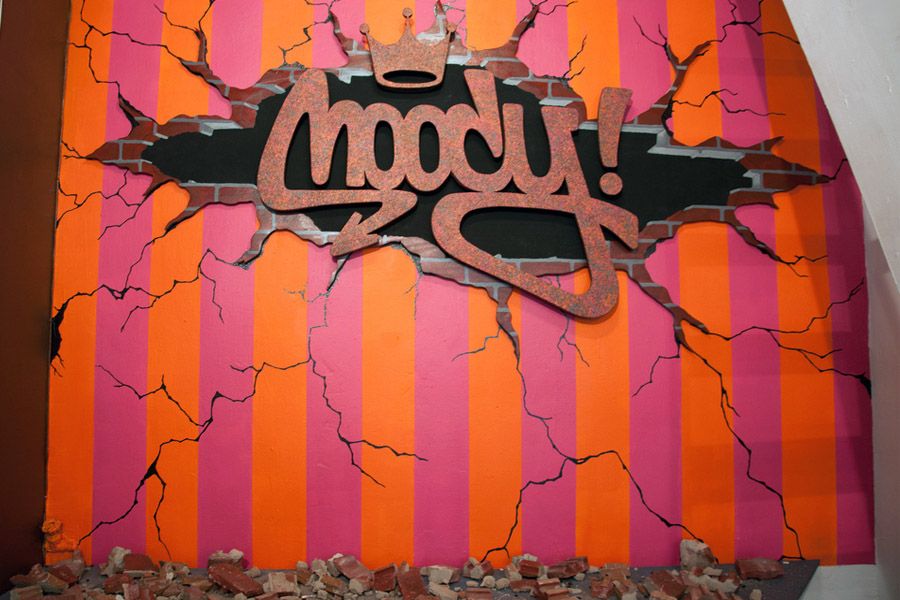

This show titled “America Runs on Graff” is a hybrid of sculptures formed from his famous hand-style and fill-ins and a mocking tone inspired by to the ubiquity of the Dunkin Donuts logo, the Coca-Cola logo and a few other American ready-mades.

About 30 pieces hang in the gallery space, from woodcuts to paintings; he tries his hand at a variety of forms.

A street art enthusiast bought his inaugural collector’s piece that night. He refused to be named and state how much he spent, but for one of the larger gallery pieces in the gallery, he said he paid “over $1000.”

“He’s great, I love this stuff,” said the collector.

The piece he purchased, a large cartoonish “M” is more in line with the street art alter-ego than the gallery persona. It’s the “M” Mutz became recognized for in his bombing days, an efficient and effective branding tool.

For outsiders, it’s easy to misinterpret the usage of the Dunkin’ Donuts logo. In fact, Mutz himself may not realize the association. Making his way in Bensonhurst, before any Brooklyn Starbucks, Dunkin’ Donuts was everywhere. Dunkin’ Donuts is a Southern Brooklyn thing, and for many locals, it is a neighborhood staple. They are everywhere, so much so that their logo and branding become a part of the subconscious.

This line of thinking can easily be transferred over to the earlier work of Mutz the vandal. His block letter outlines, script-inspired tags and even his later character work is equally pervasive.

As one fan of graffiti said of Mutz, “He is a writer’s writer.”

Mutz doesn’t hold back when it comes to his roots. Instead of using the Dunkin’ Donuts brand name, he changes it to Grumpy Guidos, poking fun at himself and presumably his old stomping grounds.

“He’s going after this whole neighborhood. It is genius…I just think no one has ever gone after guidos like that. It is great,” said the same fan.

The artwork he presents is mainly a play on the commercialism of major brands. He utilizes the Dunkin’ Donuts logo, their color palate and their font in an overarching theme of his work. He exhibits a three dimensional piece that seemingly breaks through a DD labeled wall, even leaving bits of smashed concrete on the floor.

A single marker-drawn Mutz block letter with an MTA train map was also on display. Those following his transition from vandal to artist may recognize that as his original signature style from his night-owl prowls. It was the only of its kind among the newer, more refined signatures he’s since developed.

It’s a curious anxiety to experience the facets and levels of Mutz the vandal and compare that to the current, more sophisticated Moody the street and gallery artist. The distinction is subtle, but clear.

In some pieces, it could almost seem as if he is himself uncomfortable with the commercialization of graffiti and the absence of privacy in being a bomber while doing gallery work. He, unlike some of these newer cats who want gallery recognition, started out as a vandal, with no initial plan for an artist’s studio or pieces that would one day hang on clean white walls.

He started doing bigger installation pieces sometime after 2000, almost 20 years after fighting for and winning respect on the street scene. Prior to, a few cans of spray-paint were his only tools.

As always, his work is clean and the lines are solid. He is a perfectionist. His “M” characters are, for many, the first time a character and letter combination became as significant as spelling out an entire tag name. But the context is riddled with some imbalance, as if Mutz and Moody are not exactly one yet. They may never join forces, but remain alter-egos. Mutz, who grew up with a Jansport full of cans and a pocket full of caps and Moody, who shows in packed Williamsburg galleries, may never find common ground.

Yet, this anxiety is particularly what makes these works interesting. He says it himself, he’s moody. Perhaps this delicate uncompromising between the several alter-egos is what “America Runs on Graff” actually runs on.