A Tale Of Two Cities: Chicago and New York – Part 1 Of 2

THE COMMUTE: Hey, let’s give Chicago top billing for a change. I’ve always wondered why Downtown Chicago retained its Els when New York City decided to get rid of them in Downtown and Midtown. I think I figured out the reason on a five-day trip to Chicago in August.

While most of New York’s elevated lines were built over streets — many of them from building line to building line, blocking out virtually all natural sunlight below — that isn’t the case with what remains of Chicago’s downtown elevated lines, called “The Loop.” Most Chicago Els were built along existing alleyways, something that New York has few of, and on embankments much like the Brighton line. An alleyway, for those who do not know, is a street primarily for deliveries that faces the rear of buildings. They have no windows looking out onto the alleyway; there are no storefronts facing it and there is no sidewalk. In Chicago they can extend for miles, not just for a block or two like in New York.

In Downtown Chicago, some Els were built over the streets, but the outer two tracks in downtown were removed so that the two tracks that remain are over the center of the street, allowing light to hit the buildings and street below. Contrast that with our three track Els along McDonald Avenue or New Utrecht Avenue, which reach nearly from building line to building line, or the six-track El over Brighton Beach Avenue.

Chicago built its first subway line the same time we were constructing our IND system. Most of Chicago’s rapid transit system today is still comprised of Els. There are only about nine subway stops in Chicago. My guess is that some El lines were demolished with others reduced from four tracks to two at the same time the subway was built in downtown.

How Does Chicago’s System Compare To New York’s?

It is difficult to arrive at any firm conclusions as to which system is better after only spending a few days there, but some contrasts were very noticeable. The subway cars seem tiny compared to New York’s IRT and trains are only six or eight cars in length.

I can only imagine how a Chicagoan would feel upon entering one of our spacious IND/BMT cars. I did not ride during the rush hour so I cannot compare crowding levels. Most of the subway seats faced forward on the right side of the train and backward on the left side, which made it very convenient for sightseeing and photographing from the numerous Els.

That may be changing soon. Recently, cars with longitudinal seats have been arriving, which riders are not at all happy about. Seats on local buses had higher backs with padded seats and were more comfortable than our seats.

Public Information

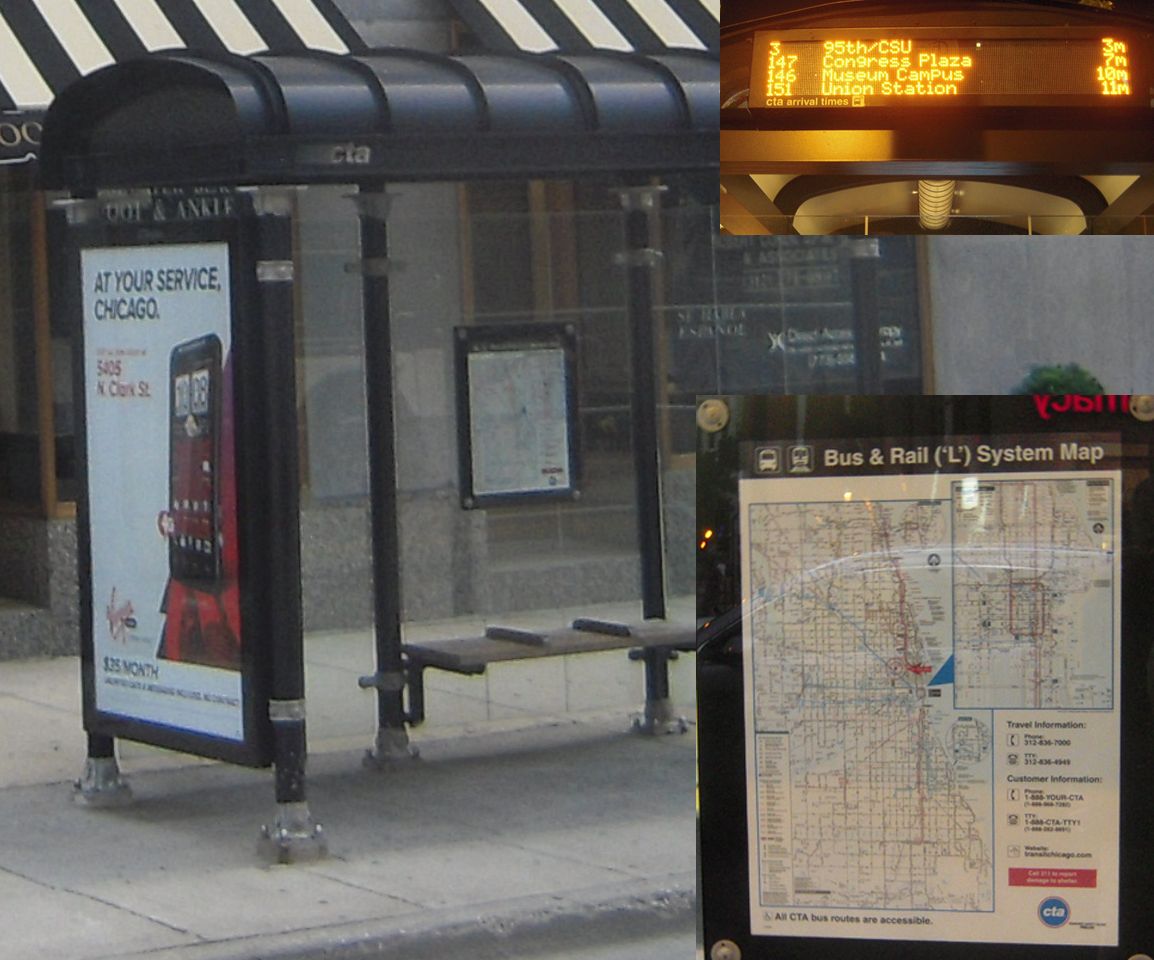

Estimated bus arrival times were provided on many downtown bus shelters. While New York opted for the modern bus shelter with the installation of CEMUSA shelters, Chicago opted for the retro “turn of the last century” look. All shelters also have complete subway and bus maps.

Every rapid transit station had clear system maps also showing bus routes as well as strip maps for rapid transit lines stopping at that station.

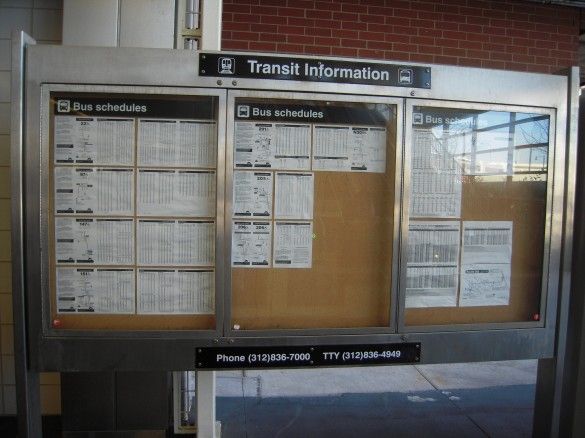

On the mezzanine level, bus schedules were provided.

At major bus transfer hubs, like Howard, bus and train estimated arrival times were posted on flat panel screens alternating with news, weather, sports and advertisements. They are far superior to our countdown time clocks.

Chicago does not use the words “street” or “avenue” in its station names, something that would not work in New York. It works in Chicago, not only because street names are not duplicated, but because the same street name is carried through multiple municipalities with a continuous street address numbering system along a grid system of streets. The relatively flat terrain allows for the grid. In New York City, street names change frequently. In Long Island, street addresses reset to the number one in each town a street passes through, further complicating matters. In short, getting around the Chicago area is much less confusing than getting around in New York.

First Impressions

We stayed in Evanston, a Chicago suburb, which is served by the purple line. Approximately six stations were having their platforms converted to concrete and were closed. We ran “express” at about 10 miles per hour, more than doubling the length of our trip to about two hours to get back to our hotel room. Just can’t seem to get away from those darn construction delays.

Since the subway is so limited and the Els only serve a small portion of Chicago and its suburbs, the bus system and commuter rail play an important role. Coordination between systems is crucial. Buses are operated by the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) and by private bus companies such as PACE. The commuter rail is operated by METRA, which I did not ride.

Fares

Except for the rails, there is a unified fare structure. The fare is $2.25 for the subway and $2 for a CTA bus, with bus transfers costing a quarter or a transfer from bus to subway. Subway and El transfers are, of course, free. However, unlike New York, where some have to pay a double fare, in Chicago there is no extra charge to ride a third bus or subway. PACE buses cost only $1.75. Buses accept smart cards, transit cards, cash and dollar bills. Trains do not accept money.

I purchased a three-day pass, something we don’t have in New York. It came in very handy because I would have used about $50 in fares taking trains and buses everywhere — too many to even keep track. There are also daily, seven-day, and monthly passes. The passes are good for express buses but not for rail. Unlike New York, Chicago’s express buses are integrated into the local bus system and you certainly know it when the bus operates express at 60 miles per hour for 20 or 30 minutes. Even in rush hour, I never saw traffic slow much below 20 miles per hour on local streets — nothing close to Manhattan’s gridlock.

Stay tuned for the second and final part of this series next Monday.

The Commute is a weekly feature highlighting news and information about the city’s mass transit system and transportation infrastructure. It is written by Allan Rosen, a Manhattan Beach resident and former Director of MTA/NYC Transit Bus Planning (1981).

Disclaimer: The above is an opinion column and may not represent the thoughts or position of Sheepshead Bites. Based upon their expertise in their respective fields, our columnists are responsible for fact-checking their own work, and their submissions are edited only for length, grammar and clarity. If you would like to submit an opinion piece or become a regularly featured contributor, please e-mail nberke [at] sheepsheadbites [dot] com.