A Glimpse Into Prospect Park’s History

Prospect Park’s Camera Obscura is pictured here around 1877, via Prospect Park

Prospect Park’s Camera Obscura is pictured here around 1877, via Prospect Park

Like so much of our city, Prospect Park sits on layer upon layer of history, with the space that was built in the 1860s having witnessed everything from the dawn of the industrial age to Brooklyn’s dramatic evolution from a rural to urban landscape. With that extensive history comes an endless supply of fascinating stories – and am New York just published a really neat piece giving us a glimpse into the Prospect Park that once was – and some of the space’s secrets you may not know about.

From a demolished dark room to a giant “Death-O-Meter” that displayed the rising number of car fatalities in the late 1920s in Grand Army Plaza, the list is a poignant and super interesting reminder of how many lives the park has touched – and, as the Prospect Park Alliance says, how the park has played and “integral role in the cycles of urban growth, decline, and renewal of Brooklyn since the 1860s.”

One of our favorite tidbits from the piece was that apparently, before Prospect Park had its zoo, rich people would “donate” animals to the area – including three bear cubs in the 1890s.

Long before Prospect Park was home to a well-visited zoo with hundreds of animals, the only exhibits it could afford were of wildlife donated by Brooklyn’s elite.

A menagerie began with a bear pit in 1890, where three bear cubs lived, though few knew of their existence. Later on deer, foxes, buffalo, peacocks, a cow and more were donated. For some unwanted animals, such as a sea lion from the Central Park Zoo whose loud barking kept nearby residents up at night, it became a safe haven. (Maybe that’s where “No Sleep Till Brooklyn” came from?)

The menagerie was demolished after the Prospect Park Zoo opened in 1935.

All these Prospect Park “secrets” that am New York writes about (you can see the entire article here) got us thinking: What is your favorite historical factoid about Prospect Park?

And, if you want to dive deeper into Prospect Park’s history, the Prospect Park Alliance has a really wonderful historical collection, including a timeline of the park’s history, details about how its historical spaces have evolved, a page about the park’s architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, neat historical photos, an audio history about the park (courtesy of local history buffs the Bowery Boys), and a video tour of the sculptures and monuments of the park (courtesy of The New Colonist).

We could spend hours looking at the Prospect Park photo archives, but here’s a glimpse of what you can see in their collection:

Photo via Prospect Park.

Photo via Prospect Park.

Brooklynites participate in maypole dancing on the Long Meadow in 1918.

Photo via Prospect Park.

Photo via Prospect Park.

Two girls sit on tree stumps in Prospect Park in 1887. As the Prospect Park Alliance points out, Olmsted often spoke of the health benefits that Prospect Park would provide for the well-being of children. He wrote in 1868 that “the process of recreation does not involve a game. Children’s minds suffer as well as their bodies from long confinement among buildings in near proximity to one other.”

Photo via Prospect Park.

Photo via Prospect Park.

A family strolls on the Long Meadow around 1890. From the Prospect Park Alliance: “This quaint image of a father and three children seen from behind conveys the ‘pastoral effect’ that Olmsted and Vaux often spoke of when describing the Long Meadow. They described the Long Meadow as ‘one sweep of grass-land that is extensive enough to make a really permanent impression on he mind.’ Sheep and cattle grazed in the meadows until the 1930s when Parks Commissioner Robert Moses took the sheep away.”

Photo via Prospect Park.

Photo via Prospect Park.

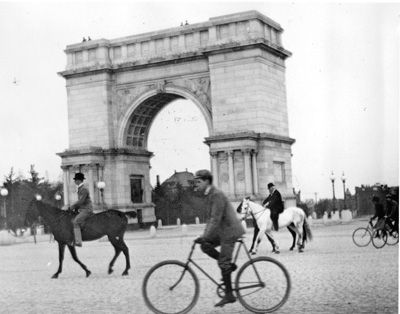

A cyclist spends time at Grand Army Plaza around 1892. The Prospect Park Alliance says: “Cycling was a popular means of transportation at the turn of the century. This lantern slide shows cyclists and horseback riders at Grand Army Plaza in front of the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch. This picture predates the arrival of the bronze sculptural reliefs and quadriga statue designed by Frederick MacMonnies in 1896.”