A Bit Of History – Flatbush Church Looking For Developer

FLATBUSH – As the borough shuffles to house all the city’s newcomers, part of its history will inevitably be gutted or succumb to full demolition. Religious institutions, with their architecturally exciting structures, brought families and communities together. For one Flatbush church, that broke ground 121 years ago in November, it too, will meet its maker at the hand of 21st-century developers.

Buzz of the new church began as early as November 30, 1897. Owner of the lot, Mrs. Benjamin Stephens settled on E. 23rd Street and Foster Avenue as the location for a new religious institution that served new families coming to the area.

Stephens was a prominent Brooklyn socialite, according to reports in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. For at least two years, she served as secretary and assistant secretary on the Board of the New York Library in 1897 and 1898. During that time, she rubbed elbows with Andrew Carnegie and Frederick Wurster, the last mayor of Brooklyn.

During the summers, Stevens partied with the elite at the exclusive Lido Golf Club on Long Island. But for her beloved Brooklyn, where she fundraised for children, she would develop the Flatbush Presbyterian Church.

The new Presbyterian Church would extend 120 feet onto E.23rd and 100 feet along Foster Avenue. Stephens, socialite-turned-savvy-developer restricted both sides of the building, “so that the church will always be assured light and ventilation,” the Brooklyn Eagle wrote in 1897. That detail would be overlooked in 1934 when a 4-story apartment building was built next to the structure.

Architect John J. Petit, whose office was five and a half miles away at 186 Remsen St., and Stephens settled on a stone facade modeled after 12th-century early English-Gothic. The basement would feature a large recreational space, a kitchen and a pantry. On the first floor, a meeting room and a women’s parlor. They choose cypress wood as an interior trim detail and the same stained glass windows still line the chapel walls.

The chapel would seat 300 and cost $10,000 to complete, $40,000 less than the church that would follow.

But the architecture is just part of what defines the 3,400 square foot religious beacon. The robust congregation and its ministers often hosted churches from different denominations. The Rev. Dr. Herbert H. Field served what seemed a robust congregation during the early 1900s. In 1913, the women of the Ladies Society of the Flatbush Presbyterian Church mobilized against Mormonism and religion’s polygamy practices. The December 14th Brooklyn Daily Eagle article pegged the movement a “crusade”.

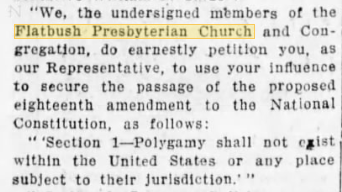

The women scribed a letter to then-U.S. Congressional Representative William M. Calder urging him to lobby for an 18th Amendment to ban polygamy:

The proposal would ultimately fail and six years later Congress would pass a different 18th Amendment – the prohibition of alcohol.

While the congregation has dwindled, the Presbyterian Church once attracted many faithful churchgoers, including R. Huntington Woodman. The organist and choirmaster, who studied under acclaimed composers Dudley Buck and César Franck dedicated at least 55 years to the religious institute.

Signs of a troubled congregation date back to 1973 when the New York Times reported the merger between the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer and the Flatbush Presbyterian Church. The idea of permanently combining two denominations under one roof was considered unorthodox. Back then, the churches settled on continuing separate religious practices with one parishioner admitting he was “a little dubious” about the union at first.

Today, the familiar site sits on the corner of a residential intersection with the promise of being demolished or, at the very least, gutted to accommodate the borough’s housing needs. With no landmark preservation to protect its 19th-century stonework, developers can renovate with no restrictions.

Colliers International, a Canadian acquisition and brokerage firm, has listed the church at 494 E. 23rd St. as a potential development site. It touts a “unique opportunity” to acquire the underdeveloped lot, that can be developed into 16,000 square feet of residential housing – nearly five times more – as of right, with no special approvals by the city.

Other churches in Brooklyn have leased to developers – many times for 99 years – a portion of their property to be developed for housing, ranging from affordable to luxury. Flatbush (Redeemer) Presbyterian Church has expressed their wishes to remain on the premises, according to the listing. If the future developer incorporates a community facility – a church would qualify – they can potentially build out to 28,920 square feet.

Flatbush Presbyterian Church at 475 Riverside Dr. owns of the property and the market value is assessed at $1,199,000.

There’s little life in and around the church and virtually no sign of an active congregation, according to neighbors. An inactive website, disconnected telephone number, and overflowing outdoor mailbox also suggest the site has been abandoned by the congregation.