“You want to know, but you don’t want to know” – Dr. Bea On Fear And Breast Cancer

PARK SLOPE – Last September, a month before Breast Cancer Awareness Month, Tracy Tomer, 53, found a lump in her breast. She knew there was something wrong and feared it was cancer, but the thought of finding out and having it confirmed terrified her even more. She put it on the back burner and went about her days. It wasn’t until November 26, 2019, that the Brownsville resident went to the doctor. She remembers that date well because it was her 53rd birthday. In December, she had her first mammogram screening. And in January, she found out she had breast cancer.

When she found out she had cancer, the first thought that went through her head was, “I have something that can actually kill me,” she told Bklyner. But that fear lasted only a few minutes when she decided she would pick herself up and do what she needs to do to get healthy. She ended up in the care of Dr. Vivian Bea.

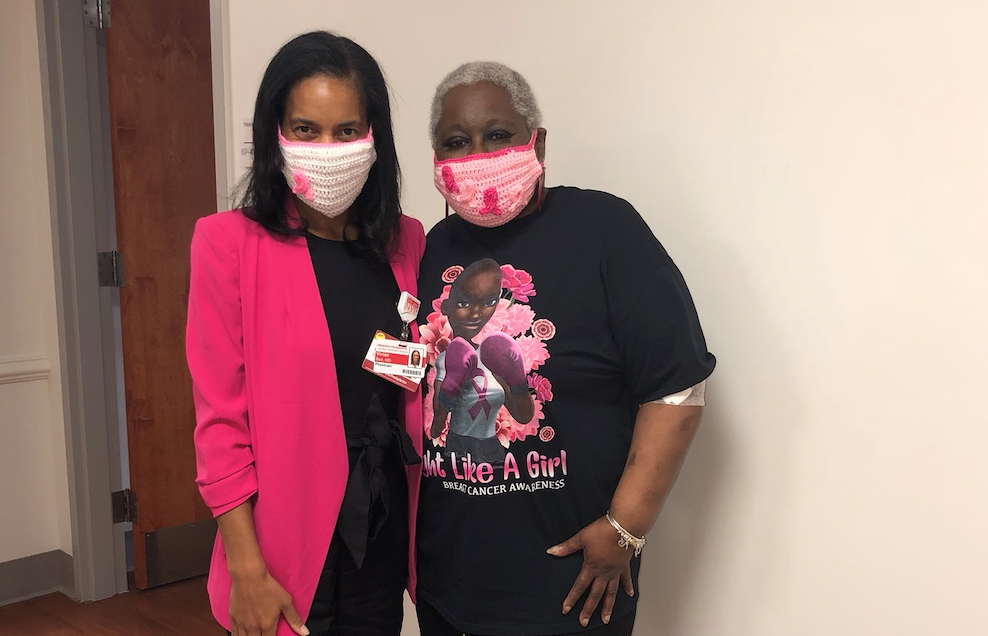

Dr. Bea, chief of breast surgical oncology at the New York-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital and assistant professor of surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, is on a mission to educate Black women about breast care. The doctor was born and raised in Washington, D.C, and decided she wanted to become a breast surgeon after medical school in Atlanta, GA. She trained at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, spending the last decade building on the foundation for addressing breast disparities. One day, she got a call about a potential new top-notch multi-disciplinary breast program in New York, a city with well-documented inequities in healthcare. She loved what she heard, and since last year, Dr. Bea has been working in Park Slope at the New York-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Black women are 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than white women. This has to do with a multitude of reasons, Dr. Bea explained. It’s not only about access; Black women who have insurance and get a mammogram screening in a timely manner are still diagnosed at a later stage, “even if they’ve done everything right,” she said. Women are also just afraid to get tested. Take Tomer, for example.

“Black women are afraid. You want to know, but you don’t want to know. The fear of hearing that you have a disease that can kill you takes a lot away from you. It takes your breath away. This isn’t something you can go to the doctor for and get a prescription of antibiotics that will kill it in two weeks. This is something that will take time, and you have to put a lot of work in,” Tomer said.

“A lot of women in this community are afraid of that. A lot of us are so busy taking care of everyone we love and everything we love, that we take less time for ourselves. And we put it off. We ignore the little signs telling us that something is wrong.”

When Dr. Bea first met Tomer, Tomer was crocheting.

“I knew she had to tell me something I didn’t want to hear but had to hear, and I was nervous, so I had my head down,” Tomer recalled. “So I told her, ‘I’m listening to you, but I’m nervous, so I’m crocheting.’ She said, ‘OK, it’s not a problem’ and made me so comfortable that I stopped crocheting and gave her my undivided attention.”

That undivided attention is what Dr. Bea makes sure to give her every patient.

“I’m a woman of color, and I can’t tell you how important it is to have trust with your patients and how many patients come in and maybe have this wall up because they don’t trust the medical field,” she said. “Or maybe they do trust the medical field, but they have comfort in seeing someone who looks like them, and it’s helping them navigate this new cancer diagnosis.”

The breast program at NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital provides multi-disciplinary care, providing breast surgery, medical oncology, radiation oncology, genetics, and navigators all in one place. Dr. Bea believes it makes a big difference when someone is diagnosed.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, a woman who’d just been diagnosed with breast cancer would come to the hospital and figure out what her next steps were. They’d sit in the room, and various doctors would come to them with information on the studies and workups they need to complete and let them know what support their clinic offers and educate them all in one sitting. During the pandemic’s peak, everything was done through telemedicine, but now, they are back to where they started.

Recently, Dr. Bea was awarded a grant from the American Cancer Society and Pfizer to investigate racial disparities in breast cancer mortality. As part of her efforts, she has been working with local churches and community organizations to raise awareness of breast cancer and the importance of breast screenings.

Every day, she has been educating women in her community in being proactive in their breast health. An average-risk woman should begin getting a mammogram screening once she hits the age of 40, Dr. Bea says, and the screening should continue every single year after that. Aside from that, women should also conduct monthly breast exams.

“If you learn your breasts and know what is normal for you if something abnormal were to appear, then the patients would have some guidance as to when they need to blow the whistle and go see a provider,” Dr. Bea explained. “It’s important also to know what the signs and symptoms of breast cancer are. Any new masses, lumps, bumps in the breast, any changes to the skin, rash, redness, swelling, any changes around the nipple, and nipple discharge—there are all signs to look out for.”

For Dr. Bea, it’s not only about educating women in the community, but it’s also about educating healthcare providers so they understand and have knowledge about breast disparities.

“I’ve had women come in who were young, who were old, who were middle-aged. I have Black women, white women, Asian women. Breast cancer doesn’t discriminate. It hits the young and the old. It’s important for me to provide excellent care to all women and to make sure quality care is given, so they have a great prognosis,” Dr. Bea said. “I know every day I am making a positive change by taking care of all women, but also women who look like me.”