Sara Erenthal: Keep On Moving On

Chances are, walking in or around Park Slope, you’ve encountered Sara Erenthal.

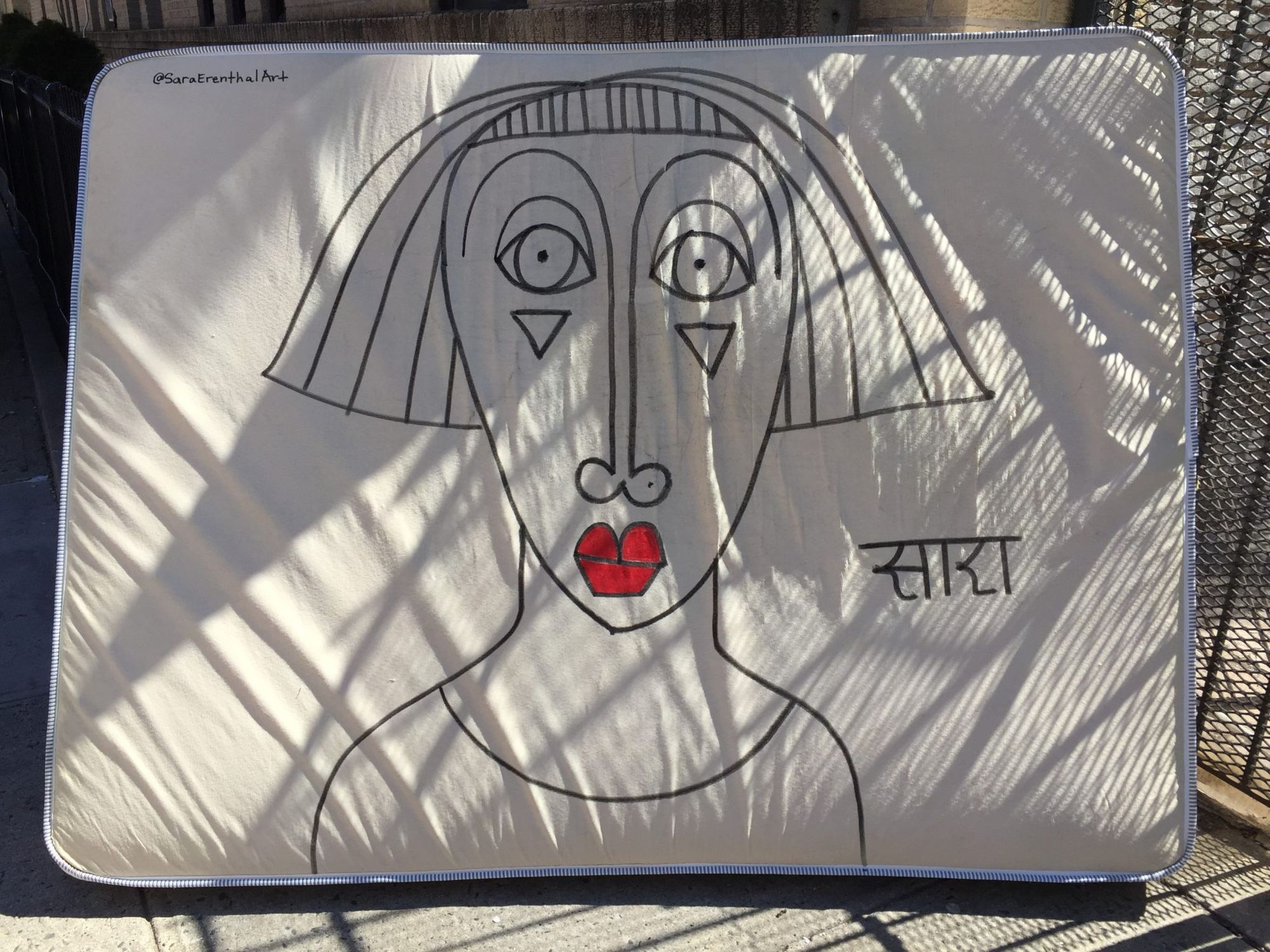

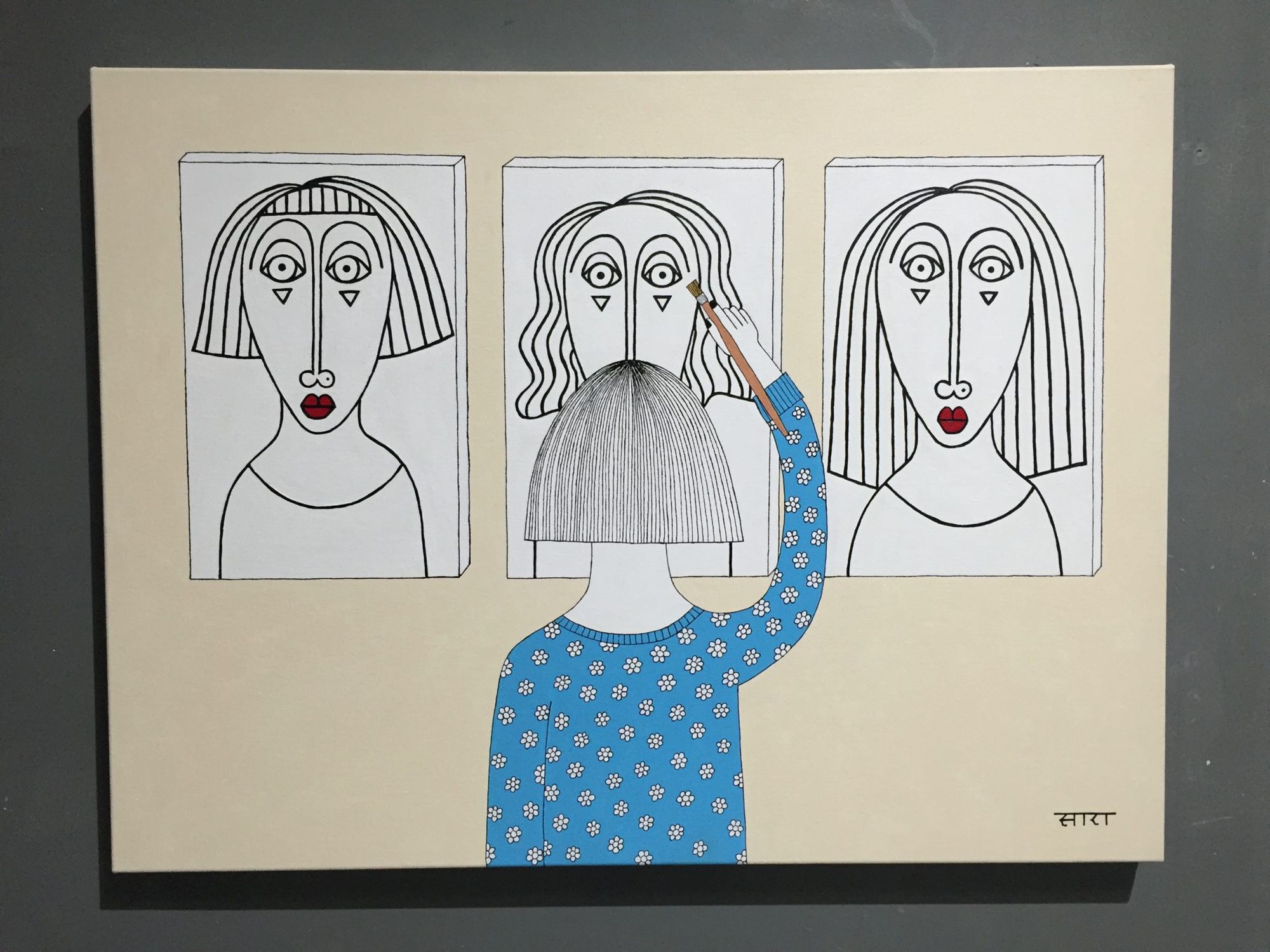

The artist often leaves her mark on storefronts, mattresses, or other discarded items on the sidewalk that might make a good canvas for one of her “subconscious self-portraits”—consisting of a linear face, wide eyes, bright red lips, and a variety of hairstyles—each of which represents a different phase of the artist’s life.

“I call it a ‘subconscious self-portrait’ because it’s not a literal self-portrait. You don’t necessarily see me. I don’t look like that exactly but it’s parts of me,” Erenthal says on a sunny Sunday afternoon outside the FiveMyles Gallery (558 St Johns Place) in Crown Heights where her current exhibition, Moving On, is on view until Sunday, April 16.

Erenthal began her foray into street art about two years ago out of necessity. “I used to collect a lot of material from the street to bring home to paint on because art supplies can get really expensive, so I’d bring home pieces of wood or frames…. One day I was in Chinatown and I saw this really beautiful old window pane and I wanted to take it home to paint on it but it was too heavy. Suddenly it hit me, I had some markers in my bag, so I drew on it.”

She learned the next day that a couple had happily hauled off her spontaneous artwork, which changed the way the artist looks at objects on the street. “I basically draw on anything, unless it’s a really beautiful piece of furniture that someone might want… I’m very considerate,” she says laughing.

“If it’s pieces on the trash pile on trash night, I’ll draw on them and then people take them,” she says. “I realize that I’m actually doing something more than just beautifying [the objects] or promoting myself. I’m actually helping save trash and giving people the opportunity to have an original piece of art.”

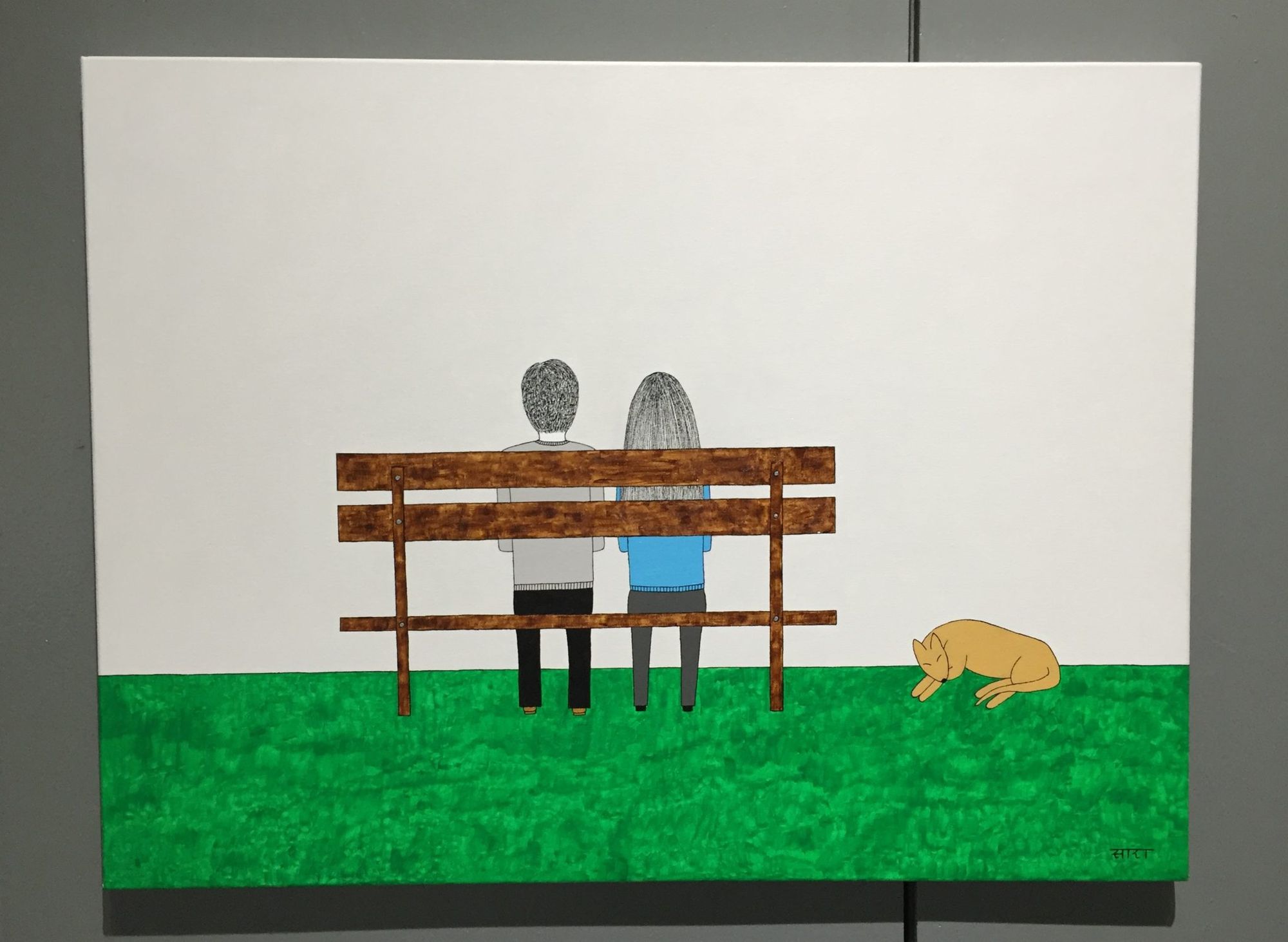

Erenthal’s exhibit, Moving On, consists of a series of narrative paintings illustrating various stages of her life. Most of the images show Erenthal from behind. “I knew that I wanted to share what I saw rather than you [the viewer] looking at me and guessing what I’m feeling,” she explains. “I want you to see, I want you to come with me on this journey and share my experiences.”

Erenthal was born in Jerusalem into a very strict and religious ultra-Orthodox Jewish family. At four, her family moved to New York [Erenthal grew up primarily in Borough Park] and returned to Israel when she turned 17.

“I never knew exactly what the life was that I wanted, but I just knew that the way I was being raised was not for me,” Erenthal recalls.

“I hated the extremeness of my community. Even within the religious community, we were from the most extreme. I hated all the restrictions and how they tried to keep us sheltered,” she says.

“I’m the kind of person that’s always curious and wants to see things, and they kept us so sheltered. I was always curious about my neighbors who were secular or not Jewish. What’s their life like? We were never allowed to see movies, read secular books, or listen to music that’s outside Jewish music, so I was just always really curious. I just didn’t like that restricted lifestyle,” she explains.

Shortly after returning to Israel with her family at the age of 17, Erenthal learned that her parents had picked out a man for her to marry. Though she resisted, she realized that she had no choice in the matter. The night before she was to meet her future husband, Erenthal ran away from home.

She initially found refuge in a kibbutz before joining the Israeli army.

“I needed a place to go and they [the army] took care of me for two years. Looking back, I think it was a good move for me at the time because coming from such a vulnerable, naïve place, to have that security for two years was really good for me and gave me an opportunity to learn about the secular world,” she says.

“At the same time, I was so naïve, I had no idea what was really going on with Israel and Palenstine,” she continues, “Now I would never want to serve in any military, but it was a solution at the time that I don’t regret. It served me well.”

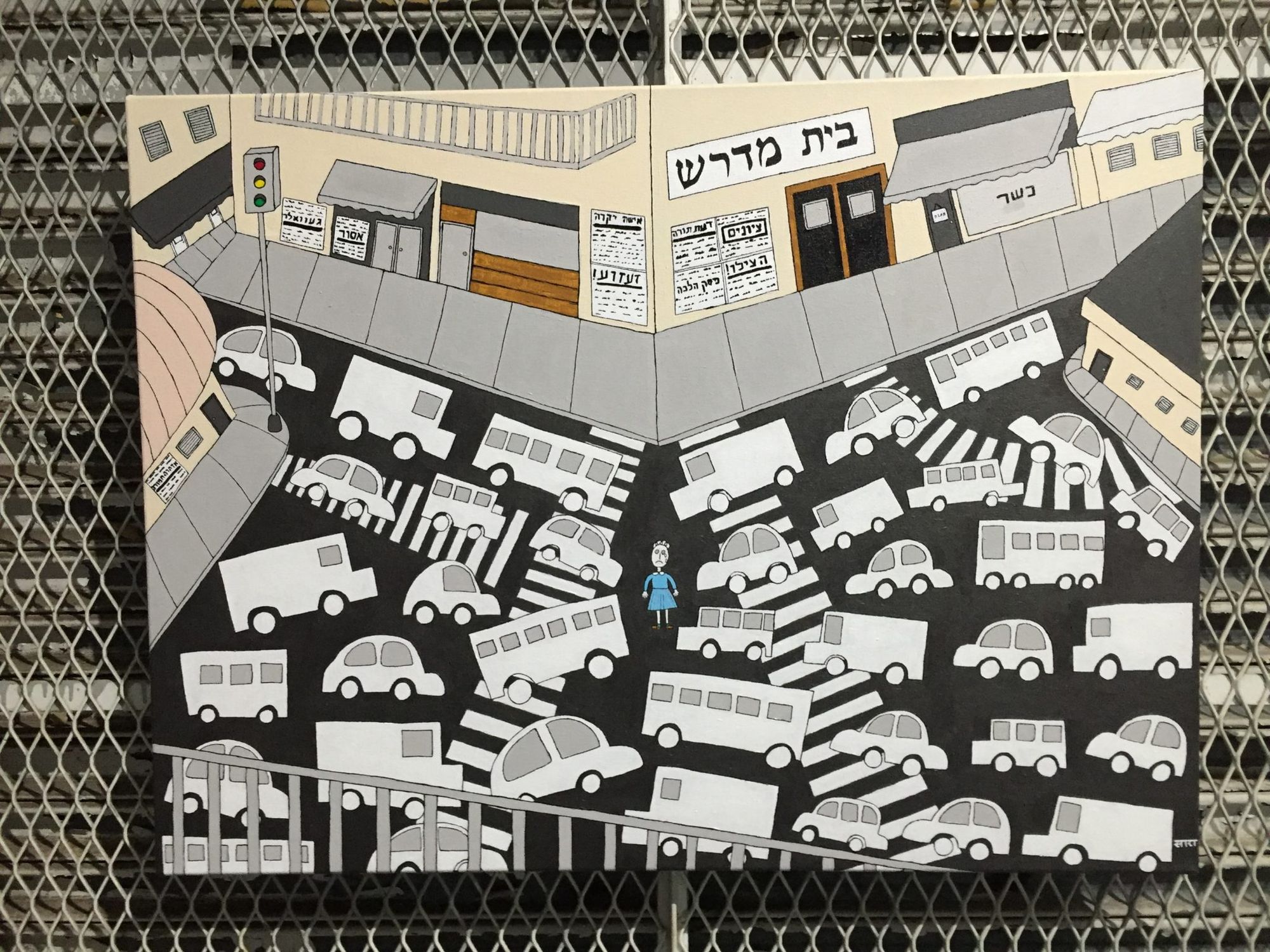

Secondhand Memory is the first painting of the series in Moving On. In it, Erenthal is a child, crying in the middle of a busy intersection. As the title suggests, the painting is based on stories Erenthal was told recounting the traumatic childhood experience of her being found in the middle of traffic after wandering away. As the artist describes it, “It’s an introduction to this little child who came into the world already lost at such a young age.”

Beikvie Hatzion (In the Footsteps of the Sheep) depicts the artist in elementary school in which she says, “The focus was definitely on the wrong thing – it was not an education.”

Indifference features Erenthal’s mother reading a book in bed, something the matriarch often did, neglecting the young artist and her siblings.

Locked Out is based on an event that occurred after the family had moved back to Israel and Erenthal was already feeling like she couldn’t “deal” with her life at home much longer.

She says, “I was sitting on the balcony in the back reading a book. It was maybe about 8pm, it was still light out. My father said, ‘I’m going to sleep so you have to come inside. I’m going to lock up and turn off all the lights,’” she recalls.

It being a nice night, Erenthal says she refused, which infuriated her father who locked her out of the house. “That was the first time that I really stood up for myself,” she says.

She adds, both Indifference and Locked Out are based on “dysfunction and wishing for better things.”

At 35, Erenthal has now been estranged from her family and the ultra-Orthodox community for half her life. “The only connection I have to that is now through my art or when I have conversations with people and they tell me about their experiences,” she says. “Sometimes I’ll tell my story and I feel like I’m telling someone else’s story.”

Attempted Romance represents the difficulty of transitioning into “the big world, the secular world,” she says, as well as the “loneliness and awkwardness” associated with not understanding the ways of her new peers.

While living at the kibbutz, a local man invited Erenthal for a romantic walk, however she didn’t realize her potential suitor’s intentions because she “didn’t know what romance look[ed] like.” When the man leaned in for a kiss, things got incredibly awkward. After taking Erenthal home, the embarrassed suitor never spoke to her again.

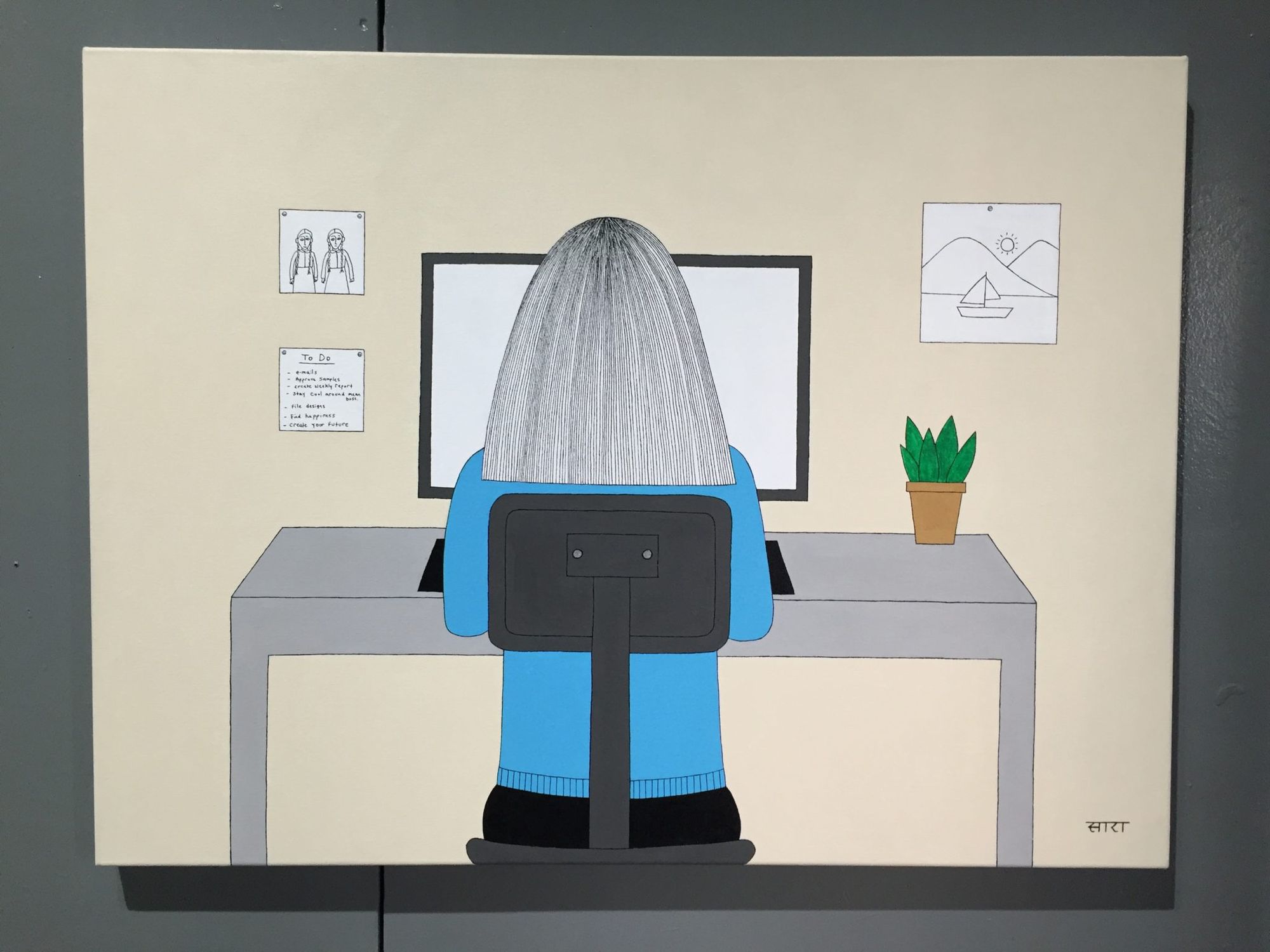

Nine To Five represents the phase of Erenthal’s life after she completed her two year military service and moved back to New York, where for the next 10 years she worked in various office jobs, as well as a nanny, and an art model.

“I always had this feeling inside me that I needed to create art but I was so busy taking care of myself, paying my bills, wanting to be normal,” she says. “I spent my whole childhood being different, I just wanted to belong, fit in, and have an apartment. I found myself only drawing when I was feeling very strong emotions—when I was in love, out of love, broken-hearted—that’s when I would draw.”

After losing a job in 2010, Erenthal put her things into storage, and went on a trip, determined to make a change. She returned to Israel for a month where a friend of hers suggested she go to India for a “cleansing.”

Erenthal was skeptical at first, thinking the idea sounded “corny” and clichéd, but three weeks after landing, for what was supposed to be a month-and-a-half visit, she ended up staying for two years (with a couple of jaunts to Thailand).

“That was the first time in my life that I had free time and I started drawing every day. The daily practice allowed me to develop,” she muses. “When I came back to New York two years later, I was so into it I just couldn’t imagine another life. That’s when I really started pursuing art professionally. I went all in.”

Erenthal’s painting Purpose illustrates this current stage of her life, where she’s discovered her passion and calling. She’s been focusing on her career in art for about seven years and has been exhibiting in solo and group shows since 2011-12.

“I’ve met a lot of really amazing people along the way who have helped me including this organization Footsteps that helps formerly ultra-Orthodox Jews,” she says.

“When I was just starting, I was so confused. I was like, ‘I want to be an artist and I don’t know where to begin.’ I went to talk to them [at Footsteps] and they mentored me and guided me,” she explains.

She’s shown her work in Footsteps’ annual member’s art show and recently won a grant from the organization that helped make her show at FiveMyles possible.

While Erenthal currently lives and works in Park Slope, she will have to move soon and is not sure what neighborhood she will head to next.

Be sure to keep your eyes peeled come the next trash night to see if you can pick up an original Sara Erenthal of your own!

Check out an interview with Sara Erenthal at BRIC.