The MTA’s Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign Misses the Mark

The recently released Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign will hurt more than it will help, argues Allan Rosen, a former director of MTA NYCT Bus Planning, because it is based on erroneous assumptions and is not as comprehensive as it needs to be.

Allan Rosen is a former director of MTA NYCT Bus Planning.

The recently released Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign will hurt more than it will help. The draft redesign is not as comprehensive as it needs to be. There are erroneous assumptions, and the report does not follow through with the stated strategies.

The plan includes some route improvements, some ideas that may be improvements, and many bad recommendations. All the route improvements could be better. Plan implementation, if not modified, will result in further ridership declines, not the increases hoped for. Many who currently have one bus access will now require multiple buses, multiple fares, and longer walks.

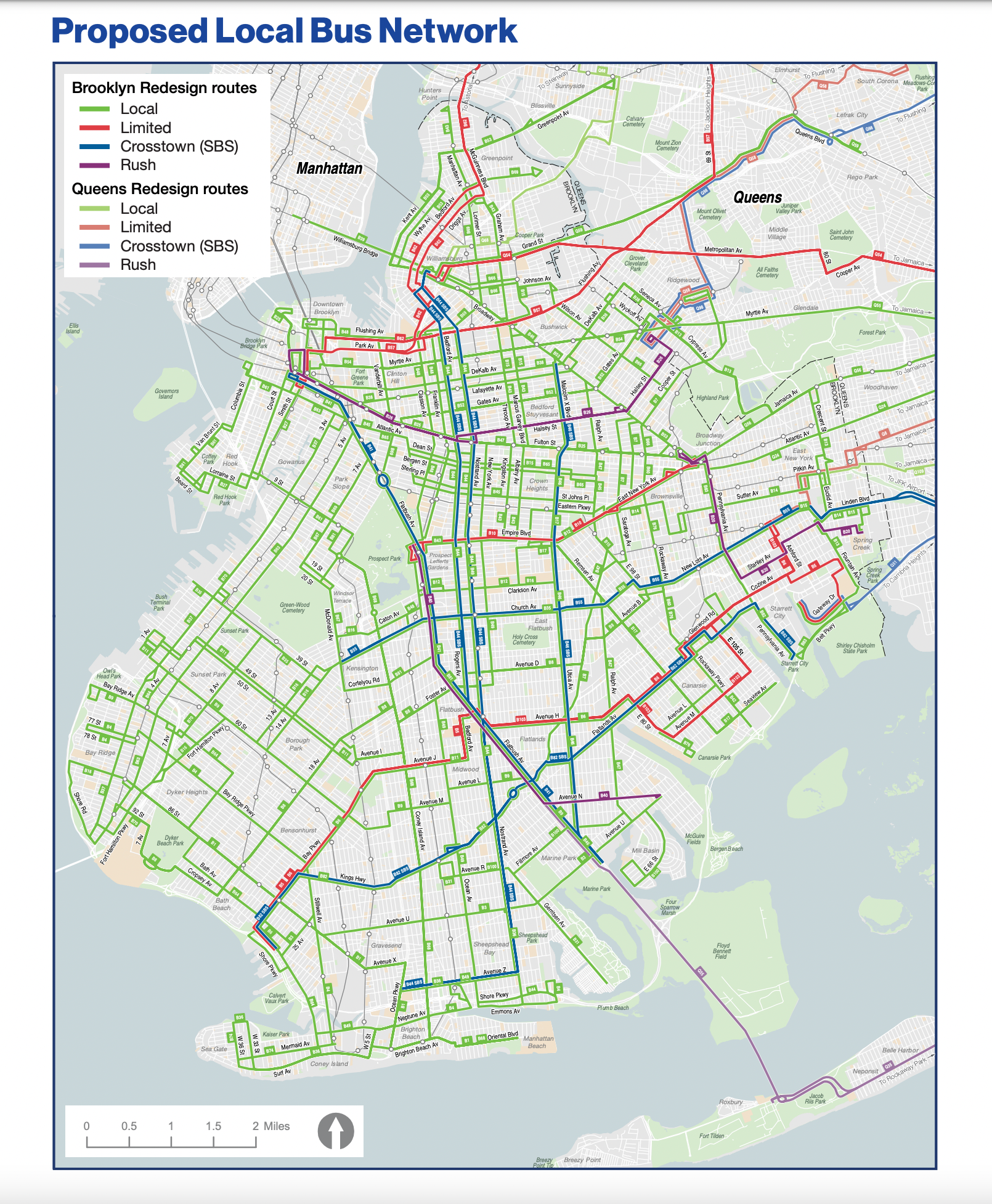

The MTA is redesigning bus networks in all boroughs. The first draft of the Brooklyn redesign was just released; Queens is being finalized, and the Bronx local bus plan and Staten Island express bus plan have been implemented. Studies in progress were halted during Covid delaying the completion of the last redesign until 2026.

Erroneous Assumptions

Since the major assumption is erroneous, the decisions made cannot further the goals and objectives.

- Individual buses traveling faster does not necessarily result in a faster trip for passengers.

Contrary to MTA's claims that Brooklyn's local buses travel at an unacceptable average speed of 7 mph, such speed is reasonable, not slow, when considering that in Brooklyn on local streets, the average automobile speed is only about 10 mph. Buses travel slightly slower than cars because they necessarily must make more stops. Of course, strategies could be employed in congested corridors to increase bus speeds there.

Overall passenger travel time is the sum of walk time to and from the bus, bus wait and travel time, and bus stop access and egress time. If additional buses or a form of rapid transit is required, those factors must also be considered. Yet, the MTA is primarily only concerned with bus speeds. Evidence that the MTA does not understand that total trip time matters is that their recent online passenger survey asks respondents not to consider bus stop walk time when calculating overall travel time.

Removing bus stops is one method of how the MTA is trying to increase bus speeds. Heavily-utilized bus stops are targeted as well as lightly-utilized ones. Most buses rarely stop at lightly utilized bus stops. They are skipped by as many as 90% of the buses, so removing them does not save significant bus travel time.

Eliminating heavily utilized stops increases dwell time at adjacent stops. Bus stop removal saves only a fraction of the claimed average of 20 seconds per bus stop removed. The likelihood of missing the bus also increases, having it pass by while walking the further distance to the nearest stop. That also increases overall travel time.

The effect of massive bus stop elimination will essentially turn all local service into limited stop service, stopping no closer than every ¼ mile (every five city blocks) or every one or two avenue blocks. Limited stop service, where buses now stop ¼ mile, will stop every ⅓ mile or longer. "Select Bus Service" is re-named "Crosstown," and a new type of service called "Rush," will have segments with ¾ mile spacing between stops.

Instead of most riders being within ¼ mile of a bus stop, they now will be within ½ or ¾ of a mile from a bus stop, adopting a European standard instead of generally-accepted U.S. standards, and imposing burdens on the most susceptible populations of elderly and disabled persons or anyone with a mobility problem, either permanent or temporary.

The notion that the way to increase bus speeds dramatically is by removing over 1,000 bus stops in Brooklyn and 1,300 in Queens is simply wrong; the negative effects of removing so many bus stops are far-reaching. The MTA also claims that a large majority of survey respondents chose faster trips over having more bus stops.

However, the MTA is not offering "more bus stops," so the point is irrelevant. More significant is that over 2,500 persons have signed an online petition opposing massive bus stop elimination. Bus riders want faster overall travel times, not necessarily faster buses individually, and certainly not fewer bus stops.

- The MTA assumes that most bus riders will tell them the plan's deficiencies which they can remedy by eliminating objectionable parts.

Ninety-nine percent of the riders are complacent and will not complain until after the plan takes effect. This is evidenced by the very small turnout of riders at the Queen's virtual meetings, no more than 1%. Community participation being inadequate, discriminates against seniors who are not computer savvy.

Not Comprehensive Enough by Not Meeting Objectives

There are Many Missed Opportunities to Improve Service

First, the MTA aims to improve interborough travel. Yet, no new bus routes are proposed to serve Manhattan, Staten Island, or the Rockaways, and no new regional services are suggested, such as a direct route connecting Sunset Park and Flushing, now illegally operated.

A new route is proposed from Central Brooklyn to JFK at the expense of severing an existing connection from northern Brooklyn. The B15 has thousands of daily riders who depend on that direct connection and chose their job because of it. A new direct connection to Central Brooklyn would benefit many, but it should not be at the expense of existing riders. A third route from southern Brooklyn would be well-utilized by employees and JFK visitors alike, but is not proposed.

A new route connecting the Sheepshead Bay Station to the Rockaways could cut travel times to 30 minutes from the current 90-plus minutes, a trip that can be made by car in 20 minutes. Sixty years ago, a ferry connection existed.

- The objective to straighten routes where possible, thereby improving connections and making the system easier to use, is not met.

Routes are only straightened where less service can be provided, such as along Broadway, which eliminates segments of the B46 and Q24.

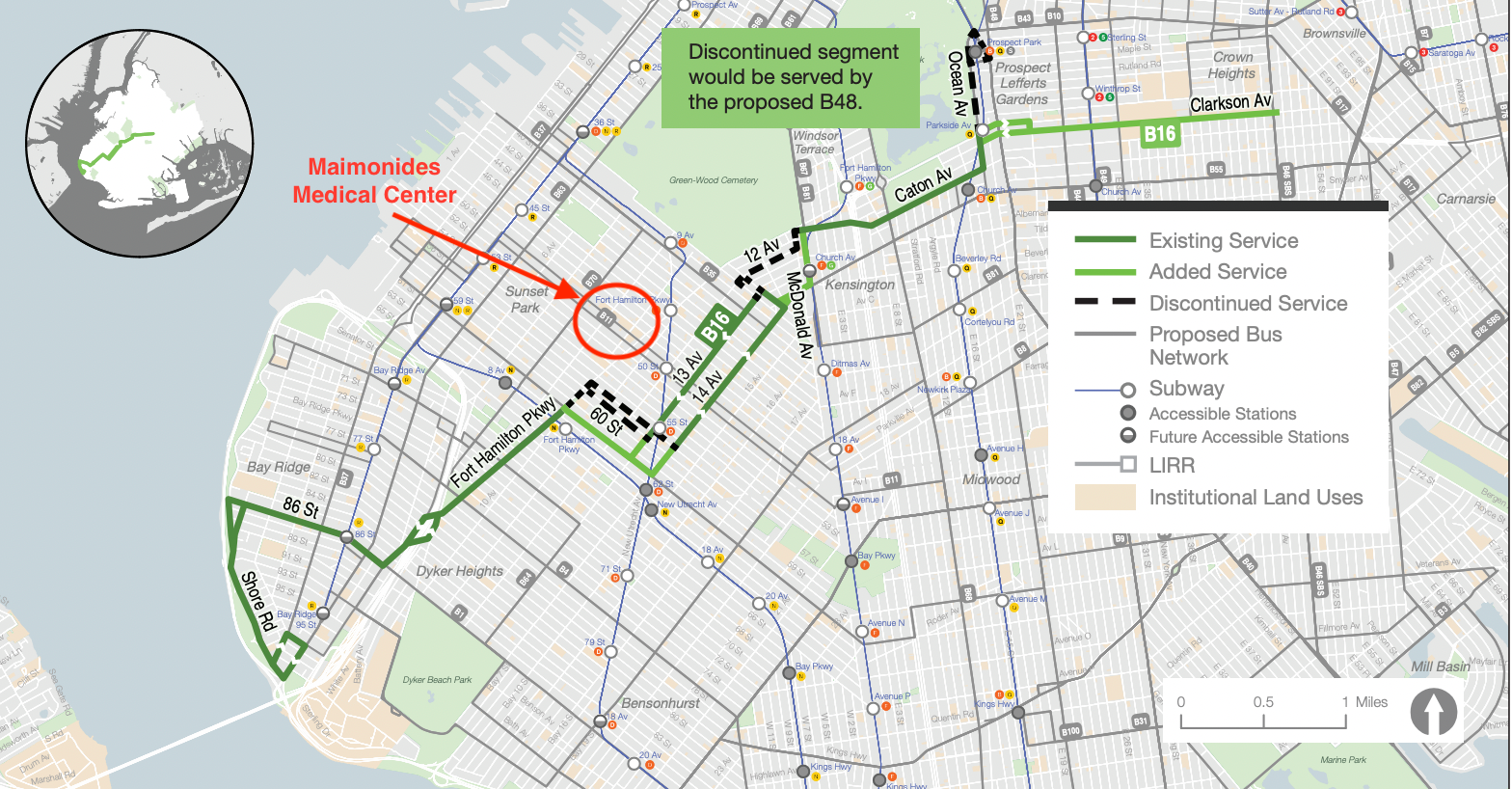

There is a proposal to reroute the B16 to 60th Street, which was rejected by Brooklyn CB 12 in 1978 and again in 2004 because 60th Street is more congested than 56th and 57th Streets. Both times the community countered with operating the B16 straight along Ft. Hamilton Parkway to pass Maimonides Hospital, which presently requires a long walk or transfer. That change would require changes to the B64.

Routes are not straightened, and many service gaps are not filled in Southwest Brooklyn. An east-west service gap in Park Slope/Cobble Hill and a north-south gap in East New York are worsened by the plan.

Instead of straightening the B49, the MTA proposes a more convoluted route that would provide more indirect service for some transferring riders. The rationale for providing a new connection to Kings County Hospital is poor because there are quicker options available.

The southern terminals of the B49 and B68 are flipped, enabling service reductions on the B1 and B49. A direct 10-minute trip between Manhattan Beach and Sheepshead Bay will be become a two-bus 30-minute trip. The B44 SBS should terminate at Kingsborough Community College, when in session, instead of duplicating the B36 to Coney Island Hospital as proposed.

- Although the Existing Conditions Report shows that Brooklyn, especially Downtown Brooklyn, is growing, there are no investments to fill service gaps, and overall service is reduced.

Report Omissions

Critical omissions reduce the credibility of the report. The MTA states the importance of the overnight network will increase but does not state whether overnight headways will be improved from the current 60 or 75 minutes.

A single route is provided between Broadway Junction in Brooklyn and Sunnyside in Queens without showing demand for a direct connection. Many current route links are broken in favor of providing new links, again without justification. There is no mention of school and summer service.

The MTA is Not Listening

It is crucial that the MTA listen and properly respond to criticisms of the network redesign, not merely by removing objectionable features, but by offering new alternatives for discussion. At the virtual meetings, the MTA merely educates the public about the written document and invites comments. There must be face-to-face discussions whereby the MTA is required to answer questions and explain their rationale.

Thus far, the MTA has ignored many criticisms of the Queens Plan, which extends into Brooklyn. They have made the same objectional proposal to reroute the Q35 four times, most recently in the Brooklyn plan.

They are not reinstating the B71 and extending it to Manhattan as proposed by local elected officials, although ridership increased by over 29% in the previous five years before it was eliminated in 2010.

Conclusions

A Brooklyn Bus Network Redesign should be comprehensive and expand and improve service for a growing borough. Instead of investing in new services, the MTA is merely filling a few service gaps, flipping route links, severing vital connections, and reducing service.

The Redesign should not leave many questions unanswered and not be undertaken as an excuse to provide less service, as I mentioned last year. Let the MTA know if any features from my plan, which includes an overnight network with improved headways, should be incorporated into their plan.

Allan Rosen is a former director of MTA NYCT Bus Planning with three decades of experience in transportation and a Master's Degree in Urban Planning. On Twitter @BrooklynBus