Meet Karen Blondel: Fighting For Justice Within NYCHA And Beyond

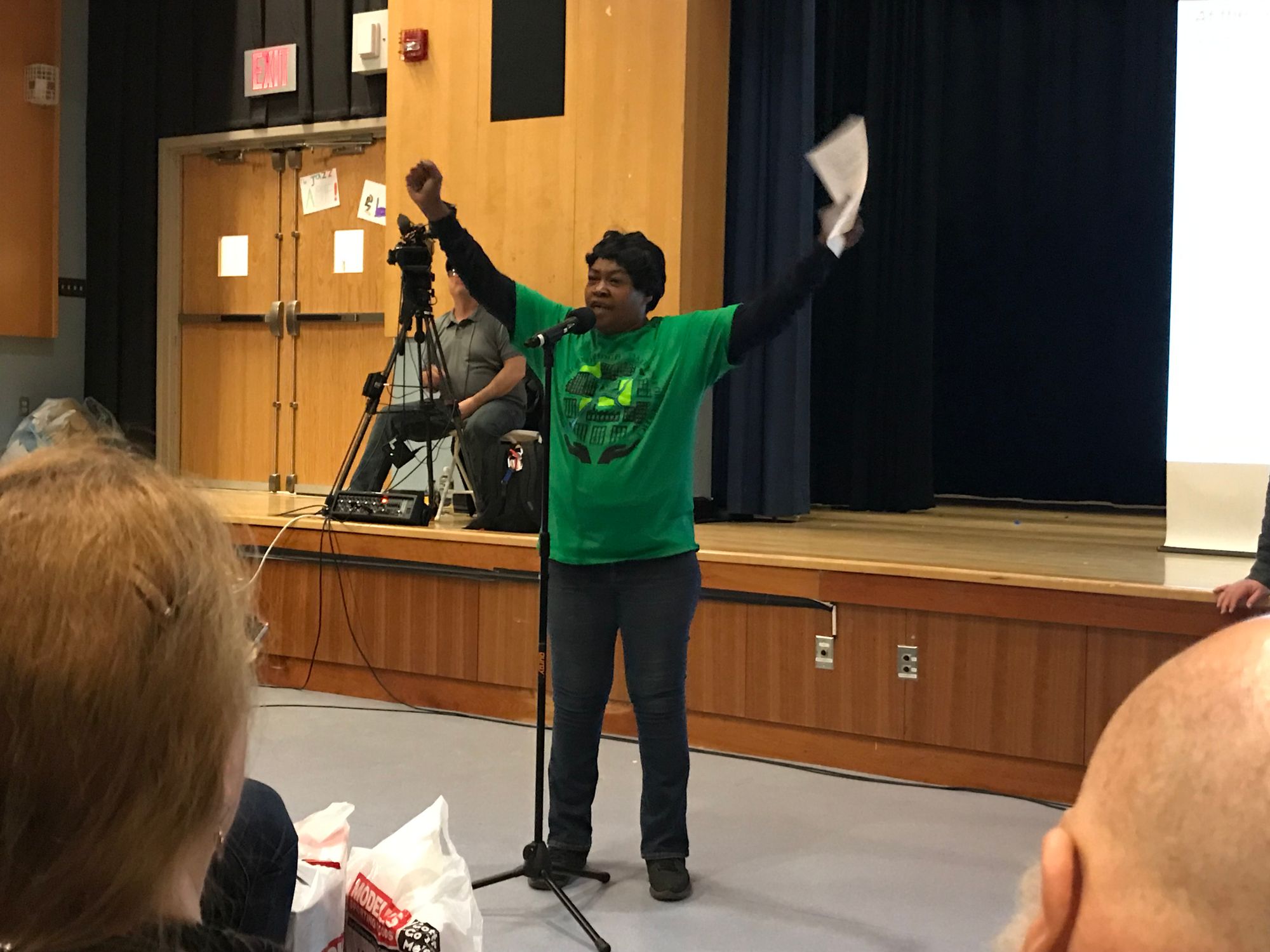

RED HOOK/GOWANUS – Karen Blondel is a familiar figure to anyone who has attended the countless Gowanus rezoning meetings over the years. The bold, outspoken advocate can command a crowd as she did in February during NYC Department of City Planning’s (DCP) rezoning open house. Leading the activist group, Gowanus Neighborhood Coalition for Justice (GNCJ), she staged a guerrilla meeting demanding to know why the area’s three NYCHA developments were not included in the city’s plans. The charismatic Blondel skillfully engaged the audience and persuaded city officials to join her on the impromptu stage. (DCP met with GNCJ to discuss the draft rezoning proposal at the beginning of March.)

“I can’t get around this work that I’m doing, whether paid or for free. It’s been something that’s been a part of who I am for quite some time now,” Blondel told Bklyner in early March. A longtime resident of the Red Hook Houses, Blondel has been fighting for the rights of NYCHA residents for decades.

“The fact that public housing was really built to contain black people after they migrated from the south to the north is a big point for me because that’s my family,” she said. “My family left the south to come to New York only to be warehoused in slums like Coney Island.”

Blondel was born in Coney Island in 1963. Her mother moved with her and Blondel’s two older brothers to Brownsville shortly after. Her mother was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis when Blondel was eight. At 14 she was sent to Coney Island to live with her Aunt Rose, a civil rights activist, at the Carey Gardens housing development while her brothers moved in with another aunt. A year later, her mother suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 36. Blondel’s father, who had remarried and started a second family on Coney Island, died of an overdose in 1982, a victim of the heroin epidemic at the time.

“When I went to live with Rose and my mom died—of course 15-years-old is a difficult time—I did a lot of running away,” Blondel recalled. “Every time I ran away, I found a school.” An avid reader since childhood, Blondel was in specialized classes while still in Brownsville. “I went to Harlem Prep. I went to Lincoln. I went to Clara Barton and ultimately I got my high school diploma, my GED, in Utah.”

“I was 17…I felt this anxiety that my mother was gone. I needed to find my place,” she explained. “I also felt distracted in New York and I found this brochure for Job Corps…. I was trying my best to find my place, so when I saw it, I was like ‘Oh wow, this is like college. I want to go.’” She explains that it wasn’t until she arrived in Utah in 1980 that she realized the “vocational and academic training model started by the Mormon church” was for troubled teens. “When I got off the plane, there were hundreds of Bloods and Crips,” she recalled.

Though she initially planned to study carpentry, Blondel changed her focus to commercial cooking and catering. “I feel like that vocational training paid for itself,” she said, noting that she worked in executive dining for many years and helped launch the Red Hook Community Kitchen. Blondel enjoyed her time at Job Corps, so much so that she later tried to get involved with the program in NYC’s public housing developments. “They do have Job Corps programs in New York, but I was saying be more specific to the public housing needs. Train them right there how to identify, remediate, and abate mold and lead—now you’ll have your work force. Especially with climate change and more humidity being around, mold grows, so let’s train them how to remediate that now.”

After earning her GED, Blondel “got a little homesick” and returned to Coney Island, took the U.S. Navy exam, passed it, then became pregnant. She decided to forgo the Navy for motherhood. Blondel, 56, has two adult children, Freddy and Sade, and four grandchildren.

Blondel lived briefly in a shelter with her newborn son before she was accepted into the Red Hook Houses in 1982. While she was happy to have a place of her own, “It wasn’t nice back then. It was scary as hell,” she recalled. “Remember Red Hook is industrial. It was dark. I saw a few people dead. I saw a lot of addiction at that time. I saw a lot of hopelessness.”

She also witnessed the crack epidemic take over Red Hook in the mid 80s, remembering regularly scheduled shootouts between rival gangs. “At first I was like, ‘I’m never staying here. I hate this place,’” she recalled. “I don’t like the people here. I want out of here. But then over time, I grew to really start caring about the people and about the problems, so I started advocating.”

When Blondel first moved to the Red Hook Houses, she lived in a one-bedroom apartment on Lorraine Street. After her daughter was born, she moved to a ground-floor two-bedroom on Columbia Street where she still is today. “I became the protector of the building,” she remembers. “I bought a water hose and stuck it out the kitchen window and I filled up a Barbie pool for my daughter. I had a barbecue for the whole block.” Blondel began cleaning the stoop regularly, taught the kids in the building to pick up after themselves, and planted a garden with her neighbors. “This is what started that community feeling on the block,” she said.

Blondel recalled an incident in 1992 that was the impetus for change in Red Hook—the death of Principal Patrick Daly. “That was huge. He was a well-known, well-liked principal in the area,” she explained. Daly, the longtime principal of P.S. 15 on Sullivan Street, was out searching for a student when he was caught in a crossfire and killed.

“It takes some big issue like a principal getting shot [before] local government starts saying ‘we need to do something for that area,’” Blondel said. “What came out of the shooting was AmeriCorps.” The federal volunteer program was introduced to the neighborhood in 1994 to address conflict resolution, mediation, and community building, she said.

Blondel signed up for the AmeriCorps Community Team and coordinated a women’s history event at the Red Hook Library which attracted more than 500 attendees, “including the drug dealers,” she said proudly. She also started a volunteer program to escort seniors on their errands and launched a summer Safe Streets program in which the Parks Department shut down local roads and brought scooters and skates for the community to use. “Once my year was up with AmeriCorps I started to become civically engaged with the Red Hook Houses [West] Tenants Association,” she said. These NYCHA groups are now known as Resident Councils. “I went there to try to continue to offer community support but when I got there, it was run very primitively and that bothered me.”

“I started reading what the job descriptions were for board members and I didn’t see that happening, so I was like, ‘this is where I can come in and stop them from voting for someone just based on friendship, cronyism, nepotism, get someone as a secretary who’s willing to take good notes, have a treasurer who won’t steal your money, and have a president who understands that it’s not a dictatorship….’” Blondel has unsuccessfully run for president of her Tenants Association three times.

She has increasingly grown frustrated with NYCHA Tenant Associations over the years, stating that bylaws are often not followed and funds have been mismanaged. “Just looking at the bylaws that the Tenant Associations use—in my opinion, they do not follow their bylaws, so there’s a lot of wasted time,” she argued. “If the bylaws say at each meeting you start the meeting by accepting or ratifying the minutes from the last meeting, I want to see the minutes. You don’t get them in Red Hook. You don’t get them in most of these Tenant Associations.”

She suggests that public housing residents stand up against the mismanagement. “They have to organize. They have to understand and read the bylaws and enforce the bylaws in the meetings. If nobody’s giving you the minutes to the last meeting, then the meeting should not go further. If you’re not getting financial reports, the meeting should not go further,” she insists.

Blondel adds that neighbors can also form their own association per a HUD [Housing & Urban Development] mandate stating that public housing residents can have more than one resident association, though only the NYCHA-appointed council will receive funding—$25 per unit per year, she said. When she tried posting this information at Gowanus Houses and Wyckoff Gardens, those Tenant Association presidents told her she needed approval from the management office.

About a year and a half ago Blondel began holding “Know Your Rights” workshops for public housing residents in Red Hook, telling them about the bylaws and the Tenant Participation Activities Guidebook. One topic she discusses is the AMI (Annual Median Income) requirement under the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program so public housing residents can determine if they are eligible to apply to new affordable housing developments. She also alerts those who have applied to public housing that their applications are only valid for two years and that they will need to re-apply after those two years have lapsed. Most applicants are not aware of the expiration date, she said. Blondel notes NYCHA did recently take a step in the right direction by including a note with monthly rent statements about recent updates to the resident guidelines.

The “Know Your Rights” workshops for public housing residents soon became part of Blondel’s full-time job at the Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC) and expanded to a “Know Your Rights” program for rent-stabilized and rent-controlled tenants as well.

Blondel currently works for FAC as an organizer for the Turning the Tide Environmental Initiative. Over the years, Blondel has worked in several jobs where she gained the knowledge and experience necessary for this role, including as an engineer’s assistant inspecting construction sites and developing blueprints for bridges, highways, and utility maps. “I learned a lot about manholes and sewer lines,” she said—experience that would later aid her in her work with the Gowanus Canal Superfund project.

“I didn’t particularly ask to do this, but I think I’m capable of doing this, and when I look at my strange background…I say ‘Wow. I learned everything that we actually need in a liaison for what’s happening here with public housing and with rezoning,” she noted.

In 2015, Blondel began working at Gandhi Engineering, conducting façade inspections for NYCHA buildings across the city. It was while working for Kirti Gandhi that Blondel learned a mantra which motivates her to this day. “I’ll always remember, he always told me, ‘Every human, no matter where they live in the world, needs three things: food, shelter, and love.’”

It was also during her time at Gandhi Engineering that Blondel learned about the $550 million allotted to Red Hook for post-Sandy recovery. Excited by the news and the opportunities the funding would present to her neighbors, Blondel immediately took action. “I knew what that meant in terms of Section 3 hires, but they were stationing the outreach in Coney Island and I felt with Coney Island having all of those public housing clusters that they were going to utilize their energy and resources there first and by the time it got to Red Hook we wouldn’t get s–t,” she explained. Section 3 is a HUD mandate stating that any construction project with a budget over $250,000 must hire public housing residents or low-income individuals.

“I said, ‘I’m not waiting for NYCHA to send out a flyer. I’m going to make a flyer and slap it up myself,’ she recalled. “I took my own money, made flyers, set up a meeting, and I told all the young kids from Red Hook, ‘We gotta meet. This is your opportunity.’ I told them, ‘Listen, there’s a chance in a lifetime for you to get a unionized construction job. By no means is it going to be easy, but it’s doable. I did it. You can do it. The first thing you’re going to have to do is put the pot down,’” she said. “I was being real with them.”

It was during this outreach that Sabine Aronowsky of FAC asked Blondel to consider a position at the non-profit. “I took the job as a way and a means to work close to my community because I wanted to see what $550 million—a once in a lifetime opportunity for Red Hook—could actually do. And having a background in engineering, I wanted to see it and have a say,” said Blondel.

The Turning the Tide Initiative was originally intended to educate public housing residents about the environmental burdens they face living near the lowlands, sewer sheds, brownfields, and the waterfront, she explained. “I was hired to really talk about the Superfund cleanup and the fact that the city and EPA were proposing two tanks.” One of the tanks, an 8 million gallon combined sewage overflow, is planned for the head of the canal, not far from the Gowanus Houses and Wyckoff Gardens.

“While we started off talking about the Gowanus Canal and the urban heat islands outside, it kept going back to the environment inside of [NYCHA] units, about mold, about lead, about repairs that never happened…so Sabine and I decided that we can’t be an environmental justice group and just talk about the outside environment. We have to talk about what they’re dealing with inside,” Blondel said. “These people cannot react and respond to the Canal issue when they’re dealing with mold and lead inside their apartments.”

Blondel is all too familiar with the problems in the NYCHA apartments. After finding water in her electrical outlets last year, workers “took the sink off of the wall in the bathroom and left it on the floor for nine months. They took out my walls in my shower and put up a plastic sheet for several months,” she said.

Another source of frustration living in public housing for Blondel is not being able to call 311 to report problems. NYCHA residents are required to call a Central Call Center, to report problems, which often get stuck in limbo. This inability to directly reach out to city agencies for assistance is one way that public housing residents are “siloed,” insists Blondel. “I came to this work to help public housing residents because they are the people who are veal-penned and redlined into these communities, but being poor is not the same as being stupid and I think that we miss out on a lot of intelligence,” she said. “We could learn from each other.”

“I would like to see the TPA [Tenant Participation Activity] money and resources from HPD and EPA be used…for training on building systems. People call in about no heat a lot, but sometimes it’s not that the boiler’s not working, it’s that they have a broken valve in their apartment,” Blondel said. “Just explaining to them how the heat goes from the boiler to each line, and then each radiator…making sure that they understand those simple processes so that when they make the call… they have a better understanding of what to look for and how to convey and communicate the issue.”

“It doesn’t just stop there,” Blondel said, noting that she also pushes public housing residents to get involved with greater community concerns as well. “I can be just as concerned about the white lady across the street who doesn’t want a 30-story building in front of her as I am about the senior living in public housing. I do see them as the same,” she insists. “I see them [both] with a problem that they want resolved and I’m trying to find the equity for them.”

“I think that Red Hook and Gowanus are extremely unique areas,” she continues. “It’s not only the ‘non-profit bible belt,’ it’s also one of the most creative, environmentally-conscious, feisty areas I’ve ever lived in.”

“And I love the fact that we are not just diverse, we have some integration,” she continued. “You have a lot of areas that have diversity, but everything is still separate—church, grocery shopping, everything. We are slightly more integrated, and I like that,” she said, adding that she enjoys going to the Red Hook Library to “hear my white friend play the harp, and then go there another time and see the Soul Train line.”

Despite the tough exterior she exudes when protesting, Blondel is actually very warm and lighthearted, endearing herself even to those she confronts. See her in action as she continues to advocate for public housing residents throughout the Gowanus rezoning process and tackle other issues affecting Gowanus and Red Hook.