For Women, from Women: Jazeeba Beauty Salon

MIDWOOD—The mixed-use architecture which defines the stretch of Foster Avenue from MacDonald to Ocean Avenues, pairs storefronts below, with apartments above, and hums with humans from Azerbaijan to Zambia. There’s a Bengali bakery, a Central Asian specialty market, a Dominican convenience store, Mexican bodegas, a Pakistani barber and Pakistani-owned Carvel franchise, a Polish florist and an Uzbek cobbler (and I’ve bypassed the businesses in the Newkirk Plaza.)

Two restaurants that shuttered last year, Beharry, a destination for West Indian roti, and Mamma Lucia’s, a longstanding spaghetti joint, remain points of pilgrimage on Foster, since Westwood and the Rusty Nail, respectively, have slid right into place, serving up specialties like Huevos Divorciados and vegetarian pulled “pork” (jackfruit) sliders. And maybe my favorite: a Chinese hand laundry, where the nonagenarian who opens her gate at 7:30 a.m., still presses, folds and wraps shirts in brown paper packages tied up with string… So while probably not a match for Flushing’s diversity, still, block for block, Foster Avenue surprises with a variety of unexpected products and services provided by merchants from around our spinning fidget.

Walk-Ins Are Welcome

Sandwiched between an apartment building and four row houses, 920 Foster, just west of Coney Island Avenue, is one of these mixed-used constructs, with tenants from Mexico on the upper floors, and Jazeeba Beauty Salon occupying what may have once been the parlor floor of a two-family home.

I was first drawn in by a poster in the window advertising a $6 eyebrow special. (The special has long expired, but today’s rate for eyebrow threading is still so reasonable at $7. And for every five eyebrow sessions you pay for, you get the sixth free!) I drop in. A girl, of about nine, swivels in a chair behind the front desk.

“What’s your name sweetheart?” I ask.

“Jasmine,” the girl replies.

“Jazeeba,” her mother explains, is the youngster’s given name, in Arabic, and hence the name of the salon. The owner, Naeema Kausar, has three other daughters: Uzma, Hiba, and Allia, and then there’s Noman, a son smack in the center. Mrs. Kausar is from Islamabad and has been in the United States for 15 years. Recently, she moved from an apartment on Coney Island Avenue to a house on Staten Island, pursuing the American Dream of homeownership, Brooklyn style.

She kindly agreed to this interview.

Women Only

“What made you decide to start a business?” I ask. “That’s a big deal, to get the money together, find the location, hire employees…”

“Actually it was my husband Nadeem’s dream,” she smiles. “This was not my dream.”

“Really? Have you always been good at this?”

“Yes, in 2012 I went to school for my cosmetology license.” No minor move, with five kids under fifteen at home. “Then for two years, I worked in three different salons for practice.”

“And that’s when your husband said you should have your own business?” I ask.

“Yes, usually the Pakistani salons are run by women,” Naeema explains.

“Because men don’t cut women’s hair?” I ask.

( If my hairdresser Stephen ever retires, I’ll just have to shave my head.)

“But actually, in my country now,” Naeema continues, “some men cut women’s hair. In the last ten years, in the big cities, they have the unisex salons now…”

“But not in here. It’s all female,” I note.

“Yes, because women like it this way. They feel comfortable.”

I get it; I like it this way too. It feels relaxed, as women let their hair down into the deep shampooing sink of this cozy two-room salon, whose storefront window and walls are plastered in posters of models with kohl-lined eyes, elaborately engineered hairstyles, and henna leaves traveling up slender arms.

“You can’t see into your shop. Is that for privacy?” I ask.

“Yes, most wear the hijab outside, but inside the salon, heads are uncovered.”

“In unisex salons,” explains Uzma, “women can’t get hair services and waxing, without losing their modesty.”

The Services

While the daughters help out around the shop, answering phones or sweeping up, especially at busy times like Chaand Raat, or “The Night of the Moon,” the feast ending Ramadan and kicking off Eid al-Fitr, Naema has only one full-time employee, Samina Akbar, a lovely young woman from Lahore. In New York since 2015, Samina attended a government-run beauty school in Pakistan where, as she describes it, “They learned me everything.”

And they did teach her everything. I trust Samina with my eyebrows. “Just natural, not thin,” I tell her, settling into one of only three beautician chairs. My words are unnecessary, she remembers. Samina holds a thread taut over my brow and works so quickly the pain is negligible, lassoing individual hairs in a loop of thread, then quickly tightening to pluck.

“Is threading something girls learn at home, or are they trained in the salon?” I direct my question into the floor-to-ceiling mirror.

“It’s not hard, it’s just technique.” Samina dismisses modestly. “You learn technique, and after that it’s just practice.” As any woman who’s ever had a bad brow experience knows though, it’s not that easy to get the arch right. Samina hands me a mirror and I admire my symmetrical brows: two perfect peaked roofs.

The Clients

“Who are your clients?” I ask Naeema, wondering who else benefits from this experience.

“Everybody. It’s mixed. Mostly Pakistani, but also Uzbeki, Bengali, and Jewish, too.” I don’t know why I was surprised to hear Orthodox women frequent Jazeeba; it’s Midwood after-all, we mix.

“Is going to the salon in Pakistan something women do regularly?” I ask.

“Once or twice a week. Here too.” she replies.

“What does it mean to your clients, to come here? What do women talk about?” I ask.

“Family, education. Not too much bad things. Just positive, no negative. And we don’t talk badly about people.” Naeema stresses this last point.

“So you’re not a therapist Naeema?” I joke. “You’re not giving people advice on their love life for example?”

“No, but I do give help to women.” she adds.

By this she means she networks. Naeema knows people. She connects newer immigrants to vital services that help ease the transition from old to new.

Haggling

As-salamu alaykum, a woman with henna tattoos up both arms, still fresh from the Eid al-Fitr holiday two days earlier, glides in with purpose and opens conversation. All I pick out in English from the Urdu crossfire that follows is: “seventy-five.” Then, after more lively banter, Naeema, I gather, makes her final offer: “sixty-five for each.” “Shukriya,” the woman nods and leaves, shutting the door with force.

“Did she agree to sixty-five?” I ask.

“She did.” Naeema laughs. “Today three sisters-in-law are having a marriage party,” she explains, so they want party make-up and hairstyling. And they want a discount. We’re doing it for sixty-five dollars per person.”

It’s a tradition spanning millennia, to have an all-female prenuptial gathering—a mehndi party— for the beauty rituals of mehndi, make-up and looping locks of hair into elaborate updos. It can take three hours or more for Naeema and Samina to make the family of the bride wedding-ready. The Nikkah, or legal Islamic marriage, can be done ahead of time, at a mosque, with only the immediate family present, but for the Baraat, or the wedding day, hosted by the bride’s family, both families are out in full force, putting their best satin-slippered feet forward.

The Art of Mehndi

“Does every little girl learn Mehndi?” I ask.

“Some of them, not all,” answers Naeema. “The little girls that like it, do. After high school though, most girls want to learn how to do Mehndi.”

“And where did you learn?” I ask Samina.

“At home, on my hands, and on my feet. I was about 18 and my mother’s sisters and my cousins would come over. We would practice on each other. Then they started coming to me for holidays, for weddings.”

“The young Samina must have been good,” I observed.

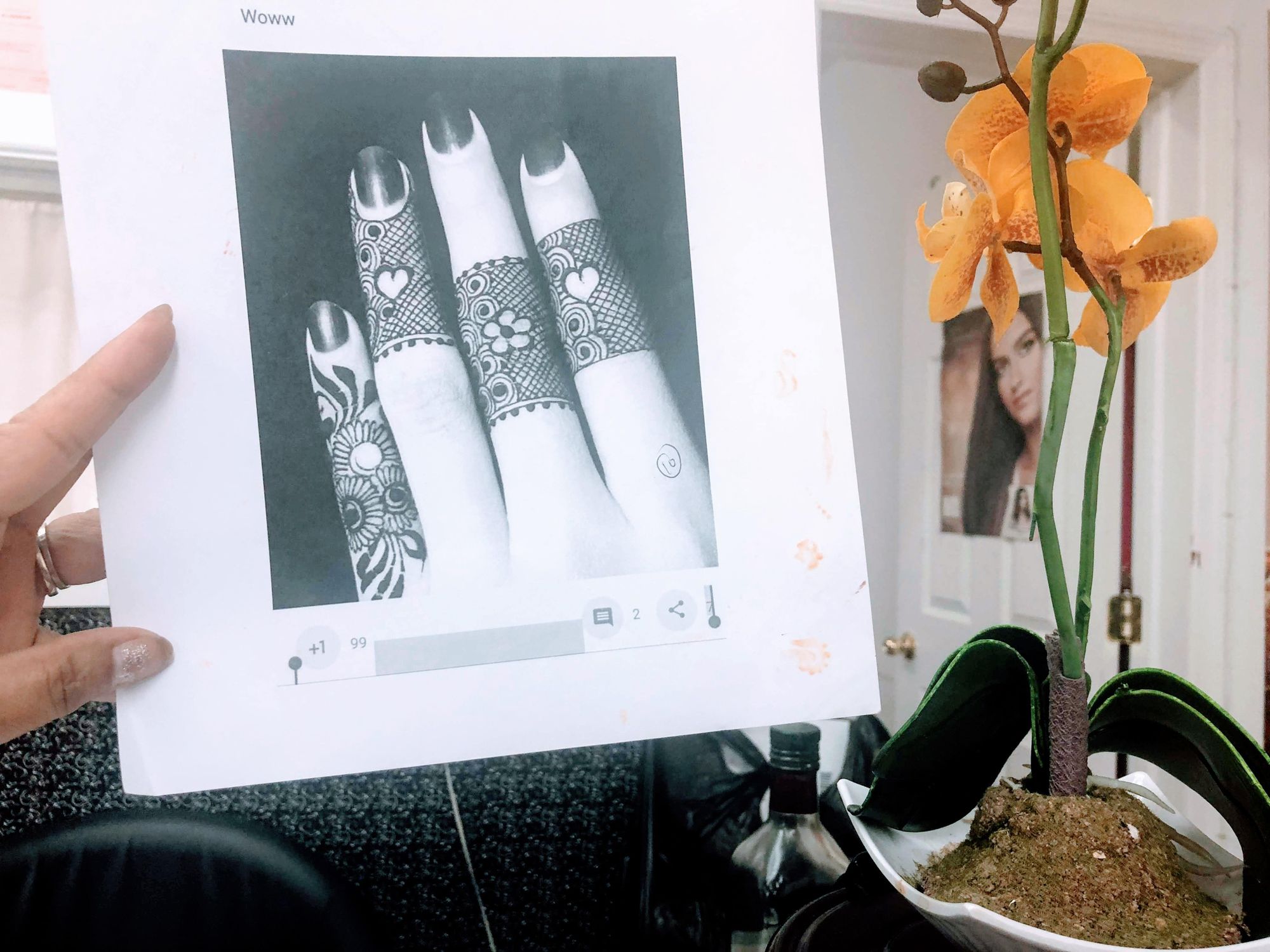

“She was,” interjects Uzma. “But you know, mehndi isn’t only flowers. Some are very abstract.”

“How do your clients decide on a design?” I ask.

“We have a binder,” Naeema hands me a binder and I flip to a page of cross-hatch basket weave bands, etched over delicate knuckles. “They can choose from here, but now many people have the images they want on their phones.”

“It’s just whatever you want it to be!” adds Uzma.

Samina enlarges an image of a red henna design starting at the pinky toe, and wending its way, like a ribbon, to the big toe, before curling across the top of the foot then tucking under the heel.

“Maroon mehndi is traditional for weddings,” she explains.

“I’d heard you hide the name of your lover somewhere in the design,” I say.

“This is more of an Indian tradition,” Uzma corrects, “but it’s getting popular in Pakistan as well.”

“Did you put your groom’s name somewhere Samina?” I ask.

“In the center of my hand.” A small smile lifts the corners of her mouth, and I visualize the opening of Samina’s painted palm towards her new husband—Usman—embedded along her life line…

What’s Next?

Naeema is looking to bring on a nail artist, which would be an excellent addition to Foster Avenue, since sandal season seems to stretch longer every year…

Where do you see this business in three years?” I ask.

“I want to expand to a second location,” she replies, “maybe down towards Avenue J or up to Cortelyou.”

And wouldn’t that be great for us gals with unruly eyebrows and dull fingertips, reaching for a touch of mehndi magic and fresh manicures? Inshallah.

Mention you saw this story Bklyner when you stop in, and enjoy 10% off any service!