COVID-19 Cases Rising Faster Among Teachers & Staff

By Matt Barnum, Chalkbeat

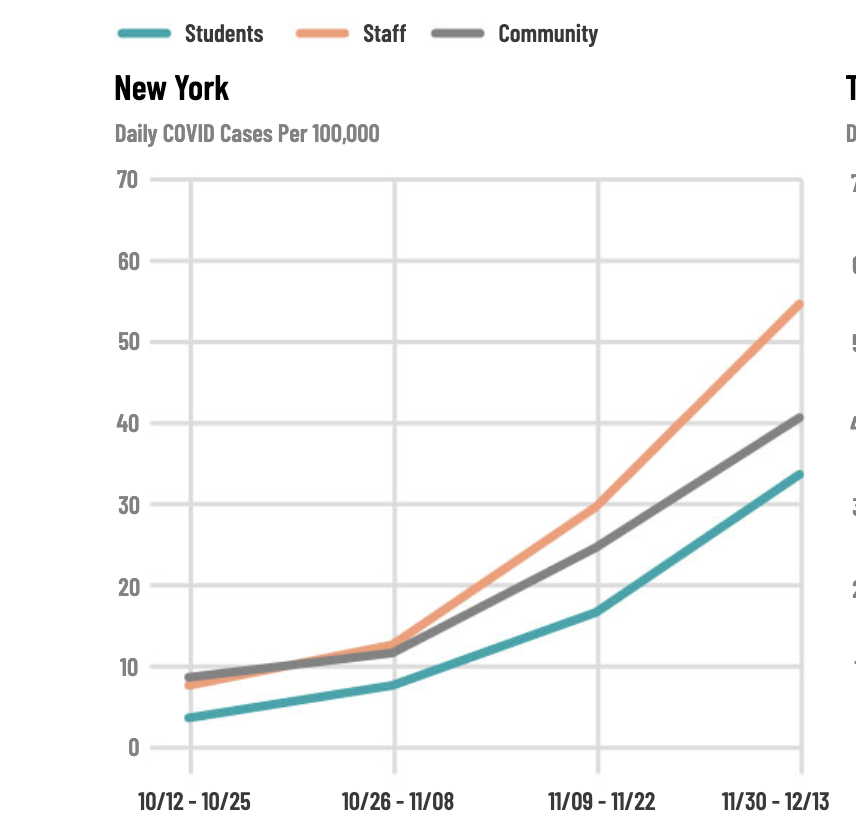

In New York, Texas, and a slice of the rest of the country where data is available, teachers and other staff where school buildings are open have higher COVID-19 infection rates than their surrounding communities.

Critically, the data does not show whether teachers caught the virus in schools, or offer definitive answers about the risks of school reopening. It’s possible the results reflect more widespread testing among teachers, and the evidence that remote teachers have lower infection rates is mixed. But the latest data complicates our understanding of the risks of school reopening.

“The fact that the staff rates are growing at a faster rate than the community rates is something we should be paying attention to,” said Emily Oster, the Brown University researcher who spearheaded the analysis and collection of this data.

In November, Oster pointed to data showing that New York teachers were no more likely to have COVID than others in their community. That is no longer the case in New York, and it hasn’t been the case in Texas for months — two states that have some of the best data on the topic.

Experts consulted by Chalkbeat say the latest data is notable but not conclusive. The findings underscore how much the information school officials have to rely on when deciding to open school buildings continues to shift.

“The data do deserve further investigation and warrant explanation,” said Rebecca Haffajee, a public health researcher at the RAND Corporation.

School staff appear to be contracting COVID at higher rates than their surrounding communities

In the absence of comprehensive data collected by the federal government, Oster’s dashboard has become one of the most cited sources of information about COVID and schools. It now includes ongoing analysis of data collected by the states of Texas and New York, as well data from schools across the country that have voluntarily provided it to Oster’s team.

In the fall, the dashboard showed seemingly low rates of infection: 0.13% of students and 0.24% of staff had confirmed COVID cases over two weeks in September, for instance. (Those figures aren’t comparable to test positivity rates, since all staff and students weren’t tested.)

An analysis Oster did for the Washington Post in November concluding that schools were relatively safe pointed out that teachers in New York had similar infection rates as the broader community.

“What should worry us is if we start to see infection rates among staff or students that are higher than in the surrounding community,” Oster wrote then.

That’s exactly what the data is now showing. Test positivity rates have ticked up over time, most recently to 0.84% for staff whose school buildings are open. And while student infection rates have remained much lower than the community, school staff have seen their infection rates outpace the community, often substantially.

Don’t see the graphic? Click here.

This trend is true in both New York and Texas, where data is tracked by the state. It was also true in the rest of the country, at least among the small number of schools that opt into reporting to Oster’s dashboard.

In New York and Texas, nearly one in 100 school staff contracted COVID in the first two weeks of December.

We don’t know from this data whether teachers are getting COVID in school

Does the latest data prove that COVID is spreading to adults in schools? Experts warn that that conclusion would be premature, particularly because the data can’t tell us where educators caught the virus.

A key complicating factor is testing. If teachers are more likely to get tested, that could skew the comparison, as more testing increases the likelihood a COVID case will be noticed and reported. School staff and students in New York City receive priority when seeking tests, and the city also conducts random testing in schools.

“One possibility is that, as more elementary schools reopened, more elementary teachers got sick as a result. Another possibility is that as more elementary schools reopened, elementary teachers were especially likely to get tested at the first sign they were feeling sick,” said Douglas Harris, a Tulane University researcher who recently published a national study on schools and COVID spread. “Unfortunately, there’s no way to distinguish between these very different interpretations.”

Indeed, in New York even teachers in schools that are entirely remote have higher infection rates than their communities. That suggests that it might not be in-person schooling per se that is leading to these patterns. (In Texas, schools are generally required to offer in-person instruction, so that sort of comparison isn’t possible.)

The data from other parts of the country, though, show that in-person teachers have substantially higher infection rates than remote teachers.

The new data is one piece in a complicated puzzle of schools and COVID

Joshua Jacobs, a Columbia University neuroscientist, became interested in the debate after talking to other parents who said they read a recent report released by the Rockefeller Foundation that argued for reopening schools with more frequent testing.

“Infection rates in schools have been very low, and generally far below the overall community rates,” the report said, citing Oster’s data.

Although epidemiology isn’t Jacobs’ field, he decided to examine the data more closely himself. “Basically no matter how you look at the numbers, the numbers are higher for teachers than for the community,” he said. “That totally shocked me.” He recently published a Medium post highlighting this fact.

Eileen O’Connor, senior vice president at Rockefeller, acknowledged the error. “I do think that sentence is somewhat misleading,” she said. “And I do think we’re going to correct it.”

She says concerns about teacher safety are legitimate, and that’s why the foundation proposed ramped-up testing of school staff and students. The incoming Biden administration is reportedly mulling a plan to pay for testing on that scale.

“What we have been promoting is testing to get ahead of infections, to understand where they are occurring, and to stop the chain of transmissions,” said O’Connor.

Oster, for her part, says she’s still inclined to push school buildings to open, particularly because of the documented harms of building closures on students. “The reason to keep schools closed is if they are very large sources of spread,” she said. “That is not true.”

A national study found that reopening buildings did not add to community spread when local COVID hospitalization rates were low or middling. Another study found that in Michigan and Washington, reopening schools could exacerbate spread if infection rates were already relatively high.

Neither of these studies specifically examined the risk to school staff. One recent study that did focused on Chicago’s Catholic schools, which opened for in-person instruction in mid-August. Between then and early October, 20 of 2,750 staff members tested positive for COVID, and 14 are believed to have contracted the virus in school. This overall infection rate (0.7%) was similar to the rest of Chicago’s overall working-age population during that period, suggesting that schools are about as risky as other workplaces.

A North Carolina study, meanwhile, found that students and staff were far more likely to contract COVID outside of school than within school. In-school transmission happened, but was rare, according to contact tracing.

Some are hoping that distribution of the vaccine, with a number of states prioritizing teachers, will offer a clearer path for schools to reopen.

“Regardless of what these data may or may not be able to tell us, having vaccines on the horizon for school staff offers real hope,” said Kimberly Powers, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina. “Once school staff can receive a vaccine that is highly effective in preventing disease, then the risk/benefit ratio of in-person learning changes considerably, and the school reopening debate should become considerably less fraught.”

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.